Apprenticeships, and the industries they benefit, are held almost exclusively by men, while New Zealand’s 65,000 care, support, mental health and addiction workers are predominantly women.

Multiple court cases identified gender discrimination in the way previous governments funded care and support workers.

These court cases led to an historic $2 billion agreement between care workers and the then National-led Government in 2017. But this agreement is set to expire in July and with it, warn advocates, the hard fought gains of care workers across the country.

So, the question has to be asked: do the latest Budget priorities and collapse of negotiations with care workers reflect the fact that five years on from the 2017 agreement, little has changed?

An historic settlement

The 2017 Pay Equity Settlement for care and support workers was reached after years of legal action led by aged care worker Kristine Bartlett, other care and support workers and their unions.

The Supreme Court determined that the care workers’ low wages and poor work conditions were the result of persistent gender discrimination.

In other words, their pay didn’t reflect the skills, experience and knowledge required but instead was based on the fact that most care and support workers were women. In New Zealand, women continue to be paid less than men.

The government of the day intervened to settle out of court before further legal action could be taken. But negotiations were limited from the outset, with the Government concerned more with curbing costs than equal pay.

The Government’s offer to the unions was about half what the unions had calculated would cover the cost of gender equal pay. The settlement also prevented these same women from taking further action on equal pay until the settlement expired.

Despite ongoing flaws in the settlement, the associated legislation delivered significant pay increases and guaranteed training opportunities for the care and support workforce.

Time is running out

After the settlement was reached, the lowest agreed wage rate for care and support workers was 121 per cent of the minimum wage; the highest rate came in at 149 per cent of the minimum wage.

Over the past five years, care and support workers’ wages have not maintained the same relativity to the minimum wage, let alone gender equal pay.

The current lowest wage rate for care and support workers is $21.84 and the highest is $27.43 per hour. The minimum wage is $21.20. That highest rate offered to care workers is only achieved after several years of training and qualifications as well as experience on the job.

Wages for care and support workers would need to range from at least $25.60 to $31.60 or more to maintain the same relativity to the minimum wage as was seen in 2017.

Deadline comes as no surprise

That the 2017 Care and Support Workers (Pay Equity) Act expires this year is not news for the Government.

Indeed, there have been some discussions on how funding models for this sector should be changed to ensure that the gender equal value of this work is maintained into the future.

However, the Government only recently offered a concrete proposal to care and support workers, despite earlier union calls for agreement and decision ahead of July’s deadline.

The offer is a 2.5 per cent to 3 per cent pay increase on current rates for the next 18 months. This is not even half the inflation rate, amounts to about 70c an hour and does not maintain the wages as gender equal.

The offer just does not value care and support work.

Care and support workers will now have to undergo another equal-pay claim process to reassess wages – despite the earlier court decisions that identified gender discrimination as the cause for low wages within the industry.

The contrast with ‘men’s work’

At the same time as care and support workers were struggling to get gender equal pay, the Government made a pre-Budget announcement to invest $230 million more into apprenticeships in 2023. This follows the $1.6 billion trades and apprenticeships training package in the 2020 budget.

There is no doubt that investing in apprenticeships is important for upskilling New Zealanders to meet labour shortages in key industries. But apprenticeships favour male-dominated industries and consequently provide significantly more opportunities for men than women.

At the end of 2020, women still comprised just 12.7 per cent of all apprentices, despite the boost to apprenticeships and focus on recruiting female candidates.

This figure has remained low despite the gendered impact of the global pandemic – 10,000 of the 11,000 New Zealand workers who lost their jobs during the first year of the COVID-19 crisis were women.

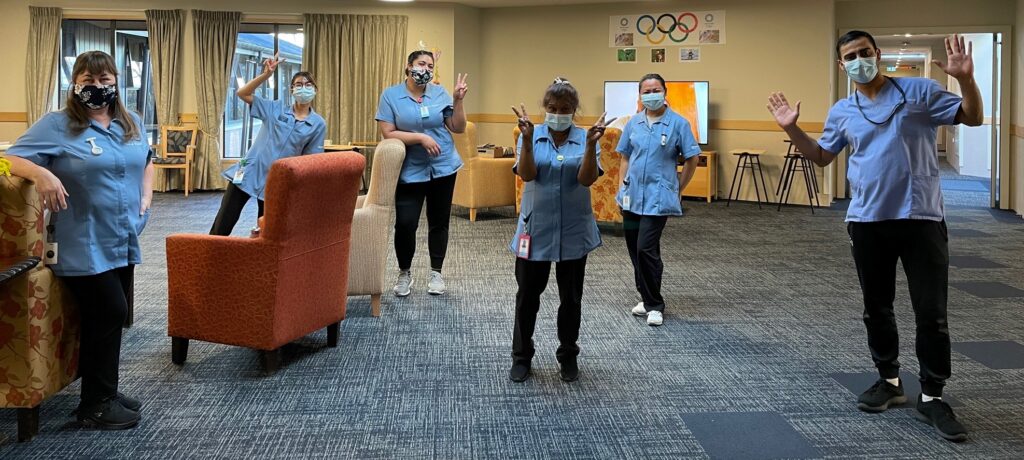

At the same time, care and support workers have operated as essential workers. During the pandemic, care and support workers were on the front line, with many going into people’s homes to look after vulnerable patients.

Despite this role and its risks, care workers struggled to access basics such as personal protective equipment (PPE) to protect themselves and the people they support or be recognised for the sacrifices they made in the course of their work.

Time for a long-term solution

The Government has had the power, but not the foresight, to conduct an updated analysis of pay ahead of the expiration of the settlement agreement.

Over the past five years, policy makers could have completed a full equal pay assessment, comparing this job not just to other female-dominated jobs in the public health sector, but to male-dominated occupations with similar skills, qualifications, risk and experience requirements.

Fully funded gender-equal pay for care and support workers could then have been included in this year’s Budget. At the very least, the pay increase on offer could have brought wages to the same level in relation to the minimum wage as in 2017.

It would have been a win for these women, for the people who rely upon their care and support, for our health-care system and our identity as a good country for women in work. Instead, it appears that no matter which government is in power, women are expected to take a back seat to profit, budgets and men.![]()

Katherine Ravenswood, PhD, is an associate professor in employment relations at the Auckland University of Technology.