The case for Health NZ to develop internal guidelines to clarify consumer/visitor behavioural expectations

Harmful exposure to violence in all its various forms is one the most significant risks for Health NZ workers and is an acknowledged priority organisational risk.

Due to the very nature of health services, this risk cannot be eliminated, will always remain present and can only be mitigated using a flexible suite of control measures.

This risk was well recognised in the lead-up to the Pae Ora health restructuring and key principles to address this were included in Te Mauri o Rongo (the New Zealand Health Charter), where good employer expectations were formally set out with clear recognition of obligations supporting worker’s rights to carry out their duties in a safe workplace.

The Health and Disability Commissioner Act 1994 directs that the Code of Health and Disability Services Consumers’ Rights contain provisions relating to the duties and obligations of providers and the rights of consumers, but is silent on provisions relating to the duties and obligations of consumers, or the rights of providers.

Due to the very nature of health services, this risk cannot be eliminated, will always remain present and can only be mitigated using a flexible suite of control measures.

While a standard of reasonableness of conduct is implicit in all the consumer rights of the Code, some consumers will not behave reasonably, impacting worker safety. This gives rise to the perception that the Code is one-sided — however the Code has no mandate for provider/worker safety.

This is because the Code’s mandate is consumer protection, due to the indisputable power imbalance existing between providers and consumers, which arises from the consumer’s lack of information and their inherent vulnerability when receiving health and disability services.

Consumers clearly do have responsibilities and may behave in ways which prevent or hinder a provider from carrying out its obligations, and such action contributes to the relevant circumstances if a provider is called to account as to how services were or were not provided.

While a standard of reasonableness of conduct is implicit in all the consumer rights of the Code, some consumers will not behave reasonably, impacting worker safety. This gives rise to the perception that the Code is one-sided — however the Code has no mandate for provider/worker safety.

A provider will not be in breach of the Code if has taken “reasonable actions in the circumstances” to give effect to provision of services. Relevant circumstances may include a consumer knowingly withholding important information at a consultation, failing to comply with a treatment plan necessary to maintain worker safety, continuing to be uncooperative or abusive after extended and supportive dialogue, or where a consumer was found to not have acted fairly or honestly in making a complaint.

Because the onus is always on the provider to prove it has taken reasonable action, it does drive a reluctance to challenge consumer behaviour, as the burden of proof is seen as excessively difficult to meet, even when this behaviour may be infringing on the rights of other consumers, or where workers report valid safety concerns.

The reasons for this performance gap is considered to be three-fold:

- The provider is fearful of repercussions that may affect its reputation.

- There is a lack of understanding through all organisational layers of how existing legislation can be appropriately used to support and maintain a safe workplace, while still ensuring compliance with the Code.

- There is no standard organisational policy and guidelines that inform how to respectfully and correctly address repeated inappropriate consumer behaviour, including the different approaches required for consumers who have altered decision-making capacity and those who do not, and the differences between a consumer covered by the Code and a visitor who is not.

Misinterpretation of the Code (racism)

Rule 7(8) states: “Every consumer has the right to express a preference as to who will provide services and have that preference met where practicable”. This clause is prone to misunderstanding regarding the extent of this right.

While it supports the freedom of opinion and expression which guarantees the rights of any consumer to express their preference as to who will provide services, it cannot be used to require a provider to enter into an illegal arrangement.

Even legitimate requests may not be able to be complied with, due to the relevant circumstances, including the consumer’s clinical circumstances and the provider’s resource constraints.

While it supports the freedom of opinion and expression which guarantees the rights of any consumer to express their preference as to who will provide services, it cannot be used to require a provider to enter into an illegal arrangement.

A consumer can state an “awful but lawful” preference, eg express a personal bias/prejudice that may be highly distasteful, eg will only accept care provided by workers of a particular ethnicity, gender, colour etc.

While such a request can be made, the provider cannot accede, as to do so would require it to promote discrimination against its own workers, an action illegal under the Human Rights Act 1993 and an act that potentiates worker mental harm under the Health and Safety at Work Act 2015.

To further support the provider’s correct course of action, clause 5 of the Code states: “Nothing in this Code shall require a provider to act in breach of any duty or obligation imposed by any enactment or prevents a provider doing an act authorised by any enactment.”

Existing worker safety protections

Legislation for managing worker safety is already in place but is under-utilised:

Health and Disability (Safety) Act 2001: NZS8134:2021 Health and Disability Services Standard is issued under this Act as a mandatory minimum level of best practice that a provider must adopt. It promotes the safe provision of services for people and whānau and encourages providers to take responsibility for safe service delivery while seeking continuous quality improvement.

Section 4.2 of the standard, “Security of people and the workforce”, sets out what is required to ensure maintenance of safe care, ie provision of policies, guidelines, information, training and equipment, implementation of relevant security arrangements for consumers and the communication of these to all people. The national agency (HealthCert) is charged with monitoring provider compliance.

Health and Safety at Work Act 2015 covers the right of a worker to a physically and mentally safe workplace. Keys parts are “section 46 — Duties of other persons at workplace”, which describes the duties and obligations of a person who is not a worker of that workplace, which applies to consumers and visitors in a health-care facility; and Regulation 14 of the Health and Safety at Work (General Risk and Workplace Management) Regulation 2016, “Duty to prepare, maintain, and implement emergency plan”, which places a mandatory duty on the provider to ensure that relevant emergency plans are implemented and maintained where required.

Human Rights Act 1993 covers the right to freedom from unlawful discrimination, including discrimination due to race, colour, ethnicity, religion, gender, sexuality and age. Section 69 covers employer obligations to investigate (on receiving a complaint) and, where proven, to prevent any repetition.

Crimes Act 1961 covers the right to prevent harm to another, self-defence against force, freedom from physical abuse, indecent assault (including intent to insult or offend), physical or sexual assault or threats to harm etc.

Victims’ Rights Act 2002 covers how a victim can expect to be treated when a victim of a crime, and has a Victims Code of Rights. While these actual rights align with the legal systems involved, the Code has eight underlying principles which are applicable to any worker harmed by workplace violence, ie personal safety, respect, dignity and privacy, fair treatment, informed choice, quality services, communication, and feedback.

Proposed plan

- Standard patient/visitor code of conduct.

- Policies: Racism policy, Visitor management policy, Patient/visitor behaviour management plan policy.

- Training of specific groups, eg security, after hours management, charge nurses/shift coordinators, ward staff, administrative staff etc.

Sample notice

Patient, Whānau and Visitor Code of Conduct

It is the responsibility of all patients, whānau and visitors to speak and act in a respectful manner.

Safety and Security

- Weapons are not allowed.

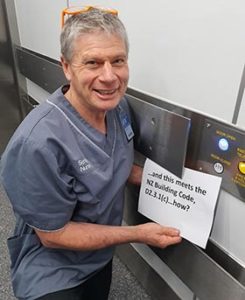

- Photography and video/audio recordings are not permitted without permission from the staff member in charge.

- Please follow the instructions of staff where requested.

Unacceptable Behaviours

Disruptive, offensive or other inappropriate behaviours or language, including but not limited to:

- Racial or cultural slurs, or other insulting remarks about race, colour, ethnicity, language, religion, gender identity or sexuality.

- Yelling or swearing.

- Making verbal threats or threatening gestures.

- Spitting or throwing objects.

- Any physical assault or attempted assault.

- Sexual remarks or behaviours.

Code of Conduct violations

For everyone’s protection, we have video surveillance and monitoring.

Please report any concerns to staff.

You may be asked to leave the facility if you cannot comply with this Code of Conduct.

If you are presenting for treatment or already receiving services, your care plan may be reviewed which could result in changes, up to and including discharge from the facility.