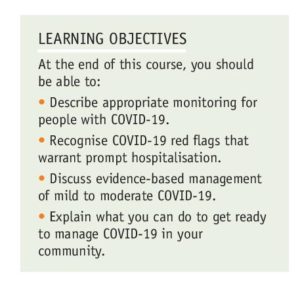

For nurses, reading this article can count for one hour of continuing professional development.

This article outlines the evidence-based processes and protocols written by Dee Mangin for the hfam.ca website, which is the basis for the COVID-19 primary care pathway in Ontario, Canada. The information and resources provided here can be adapted and used alongside New Zealand-specific guidance.

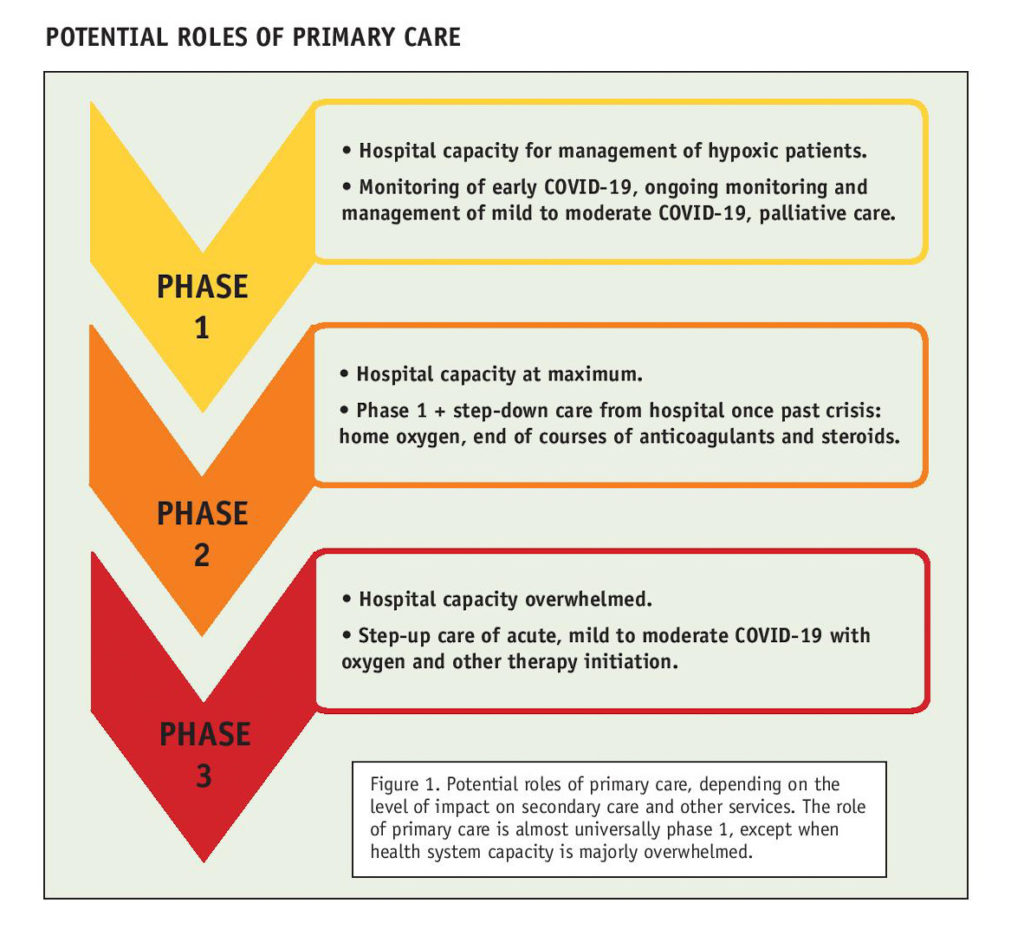

Primary care services can take a variety of roles in caring for patients with COVID-19 illness, depending on the degree to which the capacity of the health system is strained for those requiring hospital care (see diagram ‘Potential roles of primary care’, below). In general, and in particular in New Zealand, where there is good vaccine coverage, this only involves the first phase of care.

In this context, primary care involves proactive monitoring of patients from the earliest stages of COVID-19 illness (when almost all illness is mild to moderate). The aim of this monitoring is to detect, as early as possible, those who are developing hypoxia or have signs of other rapid deterioration in breathing/dyspnoea, or symptoms requiring secondary care assessment and consideration of admission. This approach also aims to maintain hospital capacity and reduce nosocomial infection by managing patients who do not need oxygen support in their homes.

Other aims are to maintain patients safely in their homes with attention to context, such as social determinants of health (eg, social isolation and access to food, shelter, heat and telephone), and to provide comprehensive primary care. This care involves management of symptoms, education, and attention to other comorbid conditions and context, including mental health needs.

Why primary care?

Population health outcomes are best when there is strong primary care, and COVID-19 is no exception. COVID-19 is also core clinical business for primary care – before vaccination, more than 90 per cent of cases could be managed without hospital admission. Primary care clinicians are skilled at managing mild to moderate infectious disease and in deciding when patients need hospitalisation.

Primary care practitioners also know their patients, which is key in bringing clinical acumen to the more concrete aspects of monitoring. COVID-19 does not occur in isolation, and those most at risk of serious illness have comorbid chronic physical and mental health conditions – these need the usual nuanced management in COVID-19 illness.

Key aspects of primary care monitoring

Connection with the patient as soon as there is a positive diagnosis is crucial. This aspect of care is different to our usual approach to viral illness, where the patient presents only if they have increasing or troublesome symptoms. With COVID-19, it is essential that contact and monitoring be started as early as possible, as recognising deterioration is key, and it means a clear baseline in symptoms and vital signs can be established.

It also means patient education and safety net systems can be put in place early, and patients will become familiar with the monitoring, self-management and safety net processes for deterioration.

Other key aspects of monitoring include:

- A clinician who knows the patient and has access to their regular health records, evidence-based resources to guide monitoring, and a template for systematic monitoring and recording.

- A systematic approach to ensure no one falls through the cracks, and a clinic-wide team approach so all staff understand the system and their roles in it.

- Patient access to a pulse oximeter; where risk indicates need; and information for patients on illness course, red flags, safety net systems and self-management strategies.

- Understanding of local access to support for basic needs (food, shelter, communication).

Proactive monitoring from the earliest stages

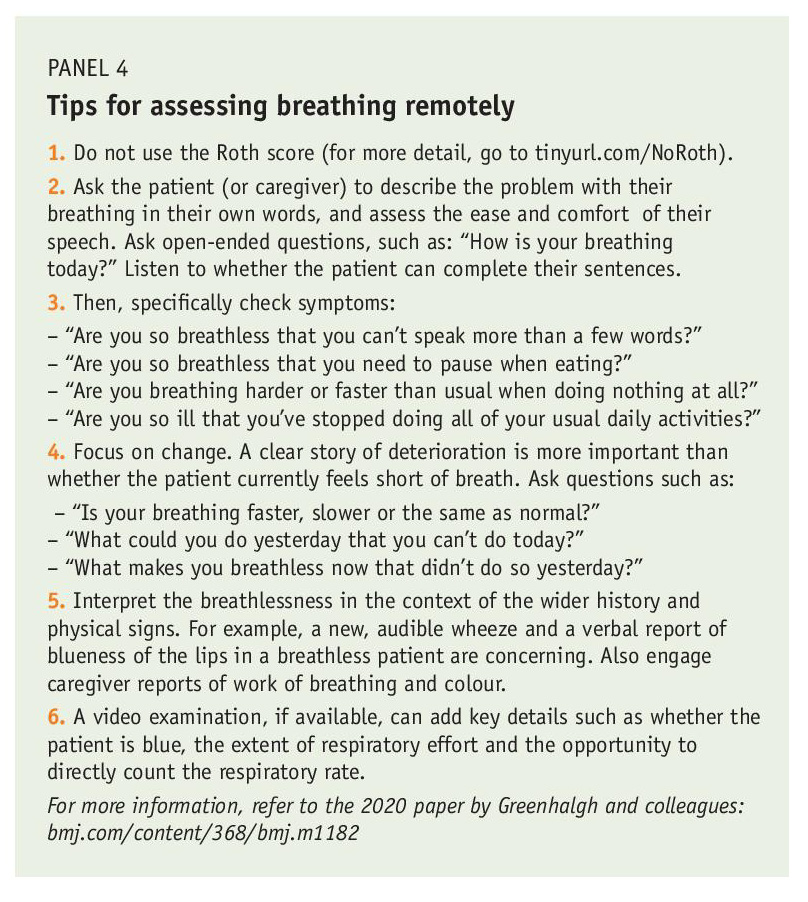

First, some general considerations about remote assessment of COVID-19 illness. New Zealand general practices are now familiar with virtual consultations. The decision on communication modality (phone or video) will depend on patient access, preferences and communication difficulties, such as hearing loss, which may make video preferable.

…those most at risk of serious illness have comorbid chronic physical and mental health conditions – these need the usual nuanced management in COVID-19 illness.

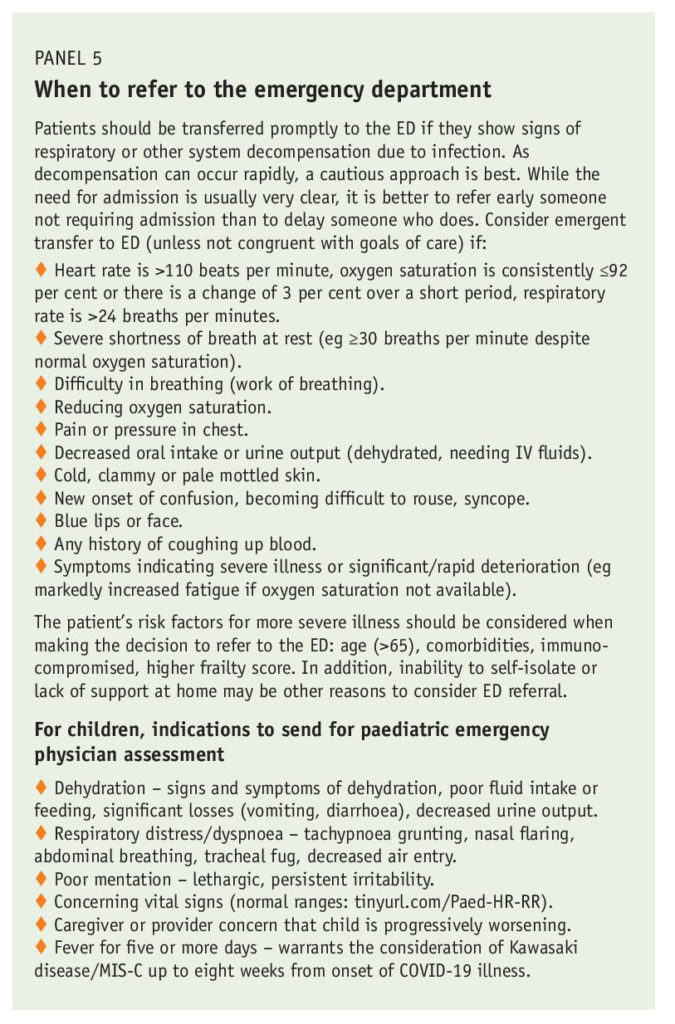

COVID-19 monitoring can routinely be provided virtually. If in-person examination is thought to be necessary because of concerns about illness severity, that often means the patient needs to be transferred to the emergency department for further assessment and to avoid delays in escalation of treatment. Chest auscultation generally doesn’t add value when determining if illness severity requires hospitalisation.

Before connecting

Scan the patient record for comorbidities that would place them at higher risk of more serious COVID-19 illness, including pregnancy, and any relevant medications (eg immunosuppressants, medications such as ACE inhibitors or diuretics that may need to be paused later if the patient has significant dehydration).

Check for history of mental illness that may warrant extra attention and support (eg history of depression or anxiety), and any indication of precarious living circumstances.

Initial assessment

Does the patient have any indication of red flags right now that would warrant immediate referral to the emergency department without further assessment? For example:

- Is the patient too breathless to talk? Can you hear them gasping on the phone? Can they speak a full sentence or only one word at a time?

- If it is a video consultation, do they look very sick (eg pale, cyanotic, gasping for breath)?

- Do they have chest pain/pressure?

Monitoring

Beyond initial set-up and triage for current red flags, there are four main aspects to monitoring patients with COVID-19 in primary care: risk assessment and determining monitoring frequency; assessment of current symptoms and change from previous; assessment of current vital signs and oxygen saturation, and changes in these from recent; hydration and assessment for red flags indicating the patient should be transferred to hospital for further assessment.

When monitoring, keep in mind the usual illness course for critically ill patients. In patients who require hospitalisation, the median time from symptom onset to dyspnoea is five days. In patients who develop acute respiratory distress syndrome, the median time to onset is three days after development of dyspnoea (about eight days after symptom onset).

However, these are medians – deterioration can occur more rapidly, and late deterioration (close to 14 days) is also possible, so where the patient is in their illness trajectory should not influence your decision on need for higher-level care.

Risk stratification

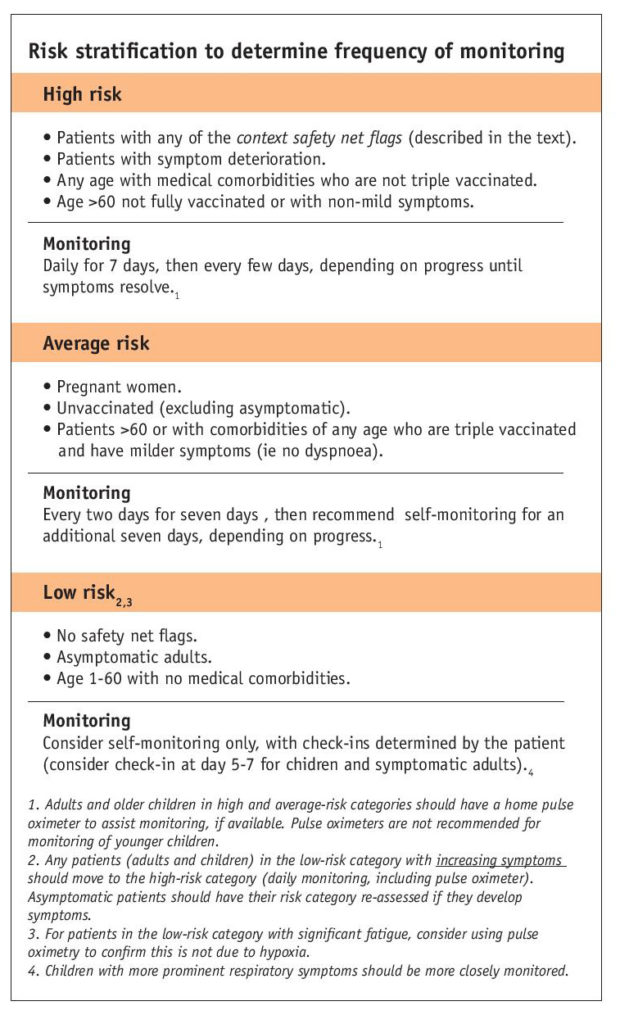

The table (below) outlines a starting framework for risk assessment to determine monitoring frequency. Note that this is a guide – if your clinical judgement means you have concerns about the patient and you feel they need more frequent monitoring, you should do so.

At current levels of vaccination in the New Zealand population, unvaccinated individuals have been placed in the average-risk category. This decision was based on data from 12 Canadian provinces and territories for the eligible population, 12 years or older. In a more highly vaccinated population, 0.08 per cent of fully vaccinated people became infected, and most hospitalisations for COVID-19 occurred in unvaccinated people:

-

- Unvaccinated people aged 12 to 59 were 42 times more likely to be hospitalised than those fully vaccinated.

- Unvaccinated people aged 60 or older were 16 times more likely to be hospitalised than those fully vaccinated.

Context safety net flags

Consider whether any of the following mean the patient needs extra support or to be transferred to a more secure setting for monitoring. If not transferred, such patients should be monitored as high risk:

-

- is socially isolated (lives alone, unable to connect with others through technology, little to no social network)

- lacks caregiver support, if needed (including a safe environment for care of children)

- is unable to maintain hydration (diarrhoea, vomiting, cognitive impairment, poor fluid intake)

- has food or financial insecurity

- receives home-care support

- has challenges with health literacy or ability to understand treatment recommendations or isolation expectations

- is unable to self-manage.

Daily monitoring template

COVID-19 is a viral illness, with COVID-19 pneumonia the most common manifestation that can increase severity to the threshold requiring hospital admission. Keep in mind the goal of monitoring: to detect significant deterioration as early as possible and promptly transfer, so therapies such as oxygen and systemic steroids can be introduced as early as possible when indicated. If the patient is subsequently found not to need admission, this is not inappropriate judgement; it reflects a safe threshold for monitoring.

Other important goals of monitoring are to reassure patients who do not need hospital-level care and to provide education on illness course, safety net instructions, advice on symptom management and attention to mental health impacts of a positive diagnosis (a positive diagnosis is anxiety-provoking for anyone, and particularly for those who are aware they are at greater risk).

During monitoring visits, check symptoms, vital signs and, most importantly, look for changes in these that might suggest deterioration. Having a template in the personal health record for standard recording is helpful, so you and others can see this change over time easily. Monitoring also involves checking for any red flags for hospital transfer.

The first monitoring visit is necessarily longer as the patient’s context must be explored, education and information provided, and questions answered. Subsequent visits are relatively quick as the patient will be used to having the information you want from them at hand.

A typical monitoring visit covers the following:

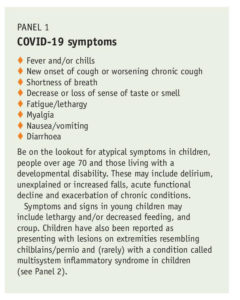

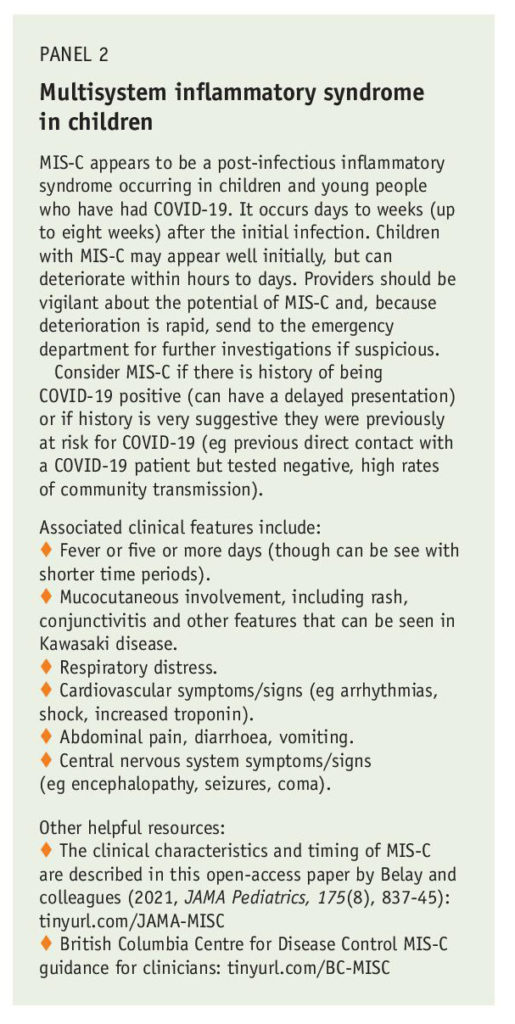

- Assess current symptoms (Panels 1 and 2) and change in symptoms (better/worse/stable).

- Ask patients to record the following vital signs until symptoms resolve:

-

- once-daily temperature (blood pressure can also be taken if the patient has access to a cuff)

- twice-daily heart rate and respiratory rate (normal paediatric ranges by age can be found at tinyurl.com/PaedHRRR)

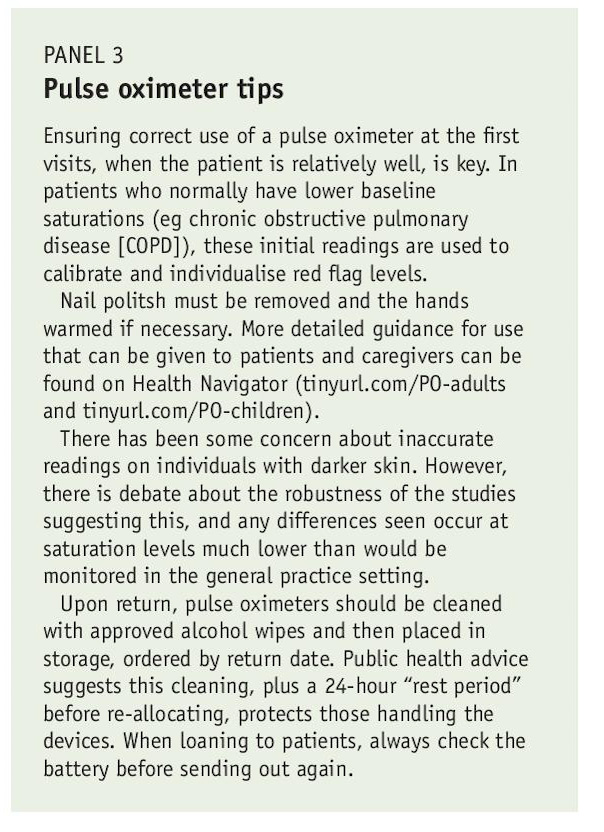

- twice-daily oxygen saturation using a pulse oximeter (Panel 3).

- Assess level of dyspnoea

- Check urine output and fluid intake. This is especially important if there is significant diarrhoea/gastrointestinal symptoms (diarrhoea is seen more commonly with the Omicron variant).

- Check for respiratory and other red flag symptoms. You are looking for the familiar signs of respiratory decompensation or other signs of decompensation due to illness that warrant prompt hospitalisation (more detail in Panel 5).

Respiratory red flag symptoms:

-

- severe shortness of breath at rest

- difficulty breathing

- increasing significant fatigue (reported in some patients as a marker for hypoxemia without dyspnoea)

- blue lips or face

- haemoptysis.

Other red flag symptoms:

-

- cold, clammy, or pale and mottled skin

- reduced level of consciousness or new confusion; poor mentation in children (lethargic, persistent irritability)

- little or no urine output; also poor feeding in children

- pain or pressure in the chest

- syncope

- parental or provider concern about progressively worsening symptoms in children

- fever >38°C for five or more days in children (may flag multisystem inflammatory syndrome – Panel 2).

- Note underlying chronic disease indicating increased risk, and monitor according to clinical need. For patients with diabetes, increase to at least daily monitoring as glycaemic control can be affected.

- Assess need for regular medication changes or advice (see detailed tips later in this article).

- Check mental health with an awareness that patients with a history of mental health issues may need extra psychological support from you. Check access to food, support or carer, financial or housing stress, and connect with local services if indicated.

- Assess whether the patient can still be managed at home (refer back to Panel 5 and consider whether a goals of care conversation is appropriate).

- Give detailed education and management advice (covered later).

- Set up a time for the next follow-up – if follow-up falls on a weekend, make plans for this.

Evidence-based management of mild to moderate COVID-19 in the community

There are four main aspects of managing mild to moderate COVID-19 in the community: patient advice and education on illness course (including red flag symptoms and timing); comfort medications and non-pharmacological comfort and hydration measures; management of comorbidities and other medications; and safety netting around red flag symptoms, and who and when to call.

Patient advice and education

Set expectations – similar to influenza, COVID-19 most often has a longer recovery time than “a virus”. Explain that the typical symptoms are cough, fever and fatigue, but they may also have breathlessness, muscle aches, sore throat, headache, and loss of sense of smell and/or taste.

Rest – fatigue is often a marker for hypoxia, and experience with more unwell patients tells us increased mechanical work of breathing may lead to increased lung damage, so it makes sense not to do anything that triggers dyspnoea/tachycardia. If patients have pulse oximeters, they can measure oxygen saturation after different activities, which is a way to reinforce this message.

Change position to aid breathing – prone lying is used for inpatients, and while there is currently no evidence for outpatients, it makes sense to change positions to move secretions and change mechanical work of breathing and improve comfort.

Hydrate – give advice to ensure adequate hydration.

Next steps – give clear guidance on who to contact if symptoms (eg, breathlessness) get worse. For example, give the patient a self-monitoring checklist with a plan for deterioration, as well as details about the contact process.

Call 111 if:

-

-

- you have severe trouble breathing or severe chest pain

- you are very confused or not thinking clearly

- you pass out (lose consciousness).

-

Call the clinic* if:

-

-

- you have new or worse trouble breathing

- your symptoms are getting worse

- you start getting better and then get worse

- you have severe dehydration, such as having a very dry mouth, passing only a little urine, feeling very light-headed

- your oxygen saturation (for those with pulse oximeters), after rechecking, is below the level acceptable for you or if it changes by 3 per cent since the previous day – the care team will advise on acceptable levels, but generally, an oxygen saturation of 93 per cent or greater is acceptable.

-

* If you don’t provide 24-hour cover, make sure instructions for evenings and weekends are clear. A formal back-up arrangement is essential for those being actively monitored in the high-risk group.

More information – email or direct patients to the latest information on self-isolation or caring for someone with COVID-19, such as Health Navigator, (which includes information for caregivers of children) and Unite against COVID-19. For those without access to email or internet, provide hard copies of useful resources.

A PDF providing information on illness course, breathing, red flags and pulse oximetry can be given to patients.

Medications not indicated

As with most viral illnesses, there are few medications useful in outpatient treatment, and treatment options suggested on social media early in the pandemic have not been supported by evidence. As with all illnesses, a calm evidence-based approach to management is key, and, above all, avoiding harm, which includes avoiding unsupported treatments. There is now clearer evidence about many of the treatments initially suggested for COVID-19, and this evidence base is constantly growing.

As with most viral illnesses, there are few medications useful in outpatient treatment, and treatment options suggested on social media early in the pandemic have not been supported by evidence.

It has been established that the following medications are not indicated for community COVID-19 care:

Hydroxychloroquine – should not be used. Recent studies indicate there is no evidence for benefit from azithromycin,1 hydroxychloroquine or the combination2 in outpatient management of COVID-19, in terms of time to recovery or risk of hospitalisation.

Antibiotics – should only be used if concomitant bacterial infection is suspected (in our experience, this is rare and presents as late deterioration) and the patient can be safely managed in the community. Usual antibiotic guidelines should be followed for uncomplicated or complicated bacterial pneumonia. Studies indicate there is no evidence for benefit from routine use of azithromycin1 or doxycycline3 (not surprising in a viral pneumonia).

Ivermectin – there is no convincing evidence for benefit on mortality, need for invasive mechanical ventilation, hospital admission, duration of hospitalisation or time to viral clearance.4

Oral steroids – should not be used in ambulant community-dwelling primary care patients. A meta-analysis shows the evidence for benefit is only in patients requiring oxygen. There is evidence that if used in milder cases (not requiring oxygen), mortality is increased.5

Think: COVID-19 is not like a COPD exacerbation.

Possibly helpful medications

Inhaled corticosteroids (ICS) – there was initial uncertainty about the potential benefits and harms of ICS. A new, large randomised controlled trial in primary care patients at risk of more serious illness suggests ICS (budesonide was studied) could shorten the time to first self-reported recovery by an estimated median of 2.9 days (11.8 days in the ICS group versus 14.7 days in the usual care group). For the outcome of hospital admission or death, the trial did not achieve the superiority threshold for ICS versus usual care.6 There are meta-analyses under way that will help answer this question.

On the basis of this data, it seems reasonable to consider ICS use for early COVID-19 in patients similar to the trial population group (aged ≥65 with ongoing symptoms from COVID-19, or aged ≥50 with specific comorbidities – ie, the high-risk group) who are interested in using them (only 80 per cent of participants in the trial ICS group used them for at least a week).7

Analyses in this trial do not provide any pointers to who is most likely to benefit. Importantly, these trial data do not support use in younger populations who are at lower risk of complications (aged <65 with no comorbidities or anyone aged <50).

Further, because vaccination was uncommon in trial participants, an important question is what effect would be seen in fully vaccinated people, who have a different illness severity and trajectory.

Paracetamol – is a safer medication for symptoms than NSAIDs. This is not specific to COVID-19, but NSAIDs increase cardiovascular risk in any viral illness.

Other comfort remedies – can be used as usual if there is evidence for benefit in relieving viral illness symptoms (eg, honey for sore throat).

Other medications – are becoming available for treatment of high-risk groups (eg, monoclonal antibodies and other antiviral agents). It will be important to watch for emerging evidence on these, as well as licensing for use in New Zealand, to determine their role in evidence-based primary care management.

Note: This information is updated on hfam.ca as new evidence on management and treatments emerges. It can be found by checking the updates tab.

What about existing medications?

- Medications for COPD and asthma should be continued (tinyurl.com/HFAM-Resp).

- ACE inhibitors and angiotensin II receptor blockers appear safe to continue in COVID-19 despite early concerns (tinyurl.com/HFAM-ACE-ARB).

- If the patient is at risk of dehydration (eg, diarrhoea), think of their risk for acute kidney injury if they are taking medications such as an ACE inhibitor or ARB plus a diuretic plus aspirin – these may need pausing to avoid AKI (acute kidney injury), which is a significant feature of more severe COVID-19 illness (see detailed advice about common medications that may need to be paused).

- If the patient is on immunosuppressant medications, consult with the relevant specialist – they may need pausing.

Paediatric considerations

For children with COVID-19, approach care as you would for any viral illness – by screening for signs and symptoms of an unstable child. Video would be preferable to phone assessment if this is possible.

While adults and older children in average and high-risk categories should have a home pulse oximeter to assist monitoring, if available, paediatric experts recommend against specialist pulse oximeters for monitoring of younger children as these are difficult to use in an unwell child, are unreliable and may distract from other aspects of assessment.

Practicalities – what to do now to get ready

Familiarise yourself with your COVID-19 pathway, roles and responsibilities, and consider how you will connect with patients as early as possible in their illness trajectory and then systematically monitor them. Do you have a personal health record template ready to allow you to easily track change over time (eg, tinyurl.com/eChart-example)?

Develop a method such as a clinic register to track all currently active patients and ensure all scheduled monitoring appointments are completed. How will weekend monitoring be ensured when required?

Do a “walk through” of the scenario of monitoring a patient, including the roles different team members will take. For example, it is good if one or, ideally, two people (so there is built-in backup) take responsibility for holding a register of currently active patients and ensuring all follow-up visits are completed. How will positive patients be added to that register?

Engage the whole team – for example, reception staff need to know that if one of the actively monitored patients calls for advice outside their scheduled appointment time, they need to be promptly put through to a clinical team member (a crucial aspect of safety netting).

… reception staff need to know that if one of the actively monitored patients calls for advice outside their scheduled appointment time, they need to be promptly put through to a clinical team member (a crucial aspect of safety netting).

If you have capacity to do so now, try to clear your existing and near-future preventive and routine care activities that require in-person attendance, in case pressure on care means these get delayed. This includes routine blood-test monitoring for chronic conditions, as increased community COVID-19 prevalence has substantial knock-on effects on availability of routine laboratory tests.

Where possible, opportunistically get a baseline oxygen saturation reading for any patients likely to have chronically reduced saturations (eg, COPD) and record it in the chart. This is very helpful when calibrating monitoring targets if they become unwell with COVID-19.

Act local – as well as your clinic team, the wider community team is also important. Models of care provision will depend on integration with other providers contributing to the COVID-19 response, in particular, public health and community organisations and volunteers. Is there a secondary care team or specialist service that is the designated local “who to call” resource for urgent advice? Do you know how to access them?

Where possible, opportunistically get a baseline oxygen saturation reading for any patients likely to have chronically reduced saturations (eg COPD) and record it in the chart.

Effective local response means working together, with good communication, to provide the most efficient care. This ensures no one falls through the cracks of medical or social care, and it avoids duplication, given the human resource pressures COVID-19 puts on the health system. Think about key local stakeholders and resources to connect with now.

How will aspects of keeping patients safely in their homes be managed (eg, food security)? Where will patients be quickly transferred and cared for if their home environment is not suitable or stable? What local palliative services are available for frail patients who would not benefit from escalated care, which could enable them to die close to loved ones (eg, home oxygen providers, local palliative care teams)?

Conclusion

Population health outcomes are better when primary care is strongest, and COVID-19 is no exception. The generalist person-focused approach of primary care is essential in providing excellent care for those patients who do not need hospitalisation, and experienced clinical judgement in determining those who do. Primary care has wide reach across the community, and distribution of patients across providers means capacity is unlikely to be overwhelmed.

The value of familiarity in unfamiliar times cannot be underestimated either – being monitored by a known and trusted team is very reassuring, and knowledge of the patient and their situation facilitates attention to the physical, mental and psychological aspects of the care needed.

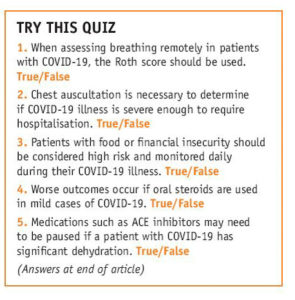

Answers to quiz: 1. False. 2. False. 3. True 4. True. 5. True.

Dee Mangin is professor and David Braley Chair in family medicine, McMaster University, Canada, and professor in the department of general practice, University of Otago, Christchurch. She is medical lead for COVID-19 care with both the McMaster Family Health Team and the Ontario Health COVID@Home Monitoring for Primary Care.

- This article was originally published in New Zealand Doctor Rata Aotearoa, and is republished here with permission.

References

- PRINCIPLE Trial Collaborative Group. (2021). Azithromycin for community treatment of suspected COVID-19 in people at increased risk of an adverse clinical course in the UK (PRINCIPLE): a randomised, controlled, open-label, adaptive platform trial. Lancet, 397(10279), 1063–74.

- Johnston, C., Brown, E. R., Stewart, J., Stankiewicz Karita, H. C., Kissinger, P. J., Dwyer, J., Hosek, S., Oyedele, T., Paasche-Orlow, M. K., Paolino, K., Heller, K. B., Leingang, H., Haugen, H. S., Dong, T. Q., Bershteyn, A., Sridhar, A. R., Poole, J., Noseworthy, P. A., Ackerman, M. J., Morrison, S., Greninger, A. L., Huang, M.-L., Jerome, K. R., Wener, M. H., Wald, A., Schiffer, J. T., Celum, C., Chu, H. Y., Barnabas, R. V., Baeten, J. M., COVID-19 Early Treatment Study Team. (2021). Hydroxychloroquine with or without azithromycin for treatment of early SARS-CoV-2 infection among high-risk outpatient adults: A randomized clinical trial. EClinicalMedicine, 33, 100773. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33681731/

- Butler, C. C., Yu, L. M., Dorward, J., Gbinigie, O., Hayward, G.,Saville, B. R., Van Hecke, O.,Berry, N., Detry, M. A., Saunders, C., Fitzgerald, M., Harris, V., Djukanovic, R., Gadola, S., Kirkpatrick, J., de Lusignan, S., Ogburn, E., Evans, P. H., Thomas, N. P. B., Patel, M. G., Hobbs, F. D. R., PRINCIPLE Trial Collaborative Group. (2021). Doxycycline for community treatment of suspected COVID-19 in people at high risk of adverse outcomes in the UK (PRINCIPLE): a randomised, controlled, open-label, adaptive platform trial. Lancet Respiratory Medicine, 9(9), 1010–20.

- WHO. (2021). Therapeutics and COVID-19: living guideline.

- Pasin, L., Navalesi., P., Zangrillo, A., Kuzovlev, A., Likhvantsev, V., Hajjar, L. A., Fresilli, S., Lacerda, M. V. G., & Landoni, G. (2021). Corticosteroids for patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) with different disease severity: A meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. Journal of Cardiothoracic and Vascular Anesthesia, 35(2), 578-84. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33298370/

- Yu, L.-M., Bafadhel, M., Dorward J, Hayward, G., Saville, B. R., Gbinigie, O., van Hecke, O., Ogburn, E., Evans, P. H., Thomas, N. P. B., Patel, M. G., Richards, D., Berry, N., Detry, M. A., Saunders, C., Fitzgerald, M., Harris, V., Shanyinde, M., de Lusignan, S., Andersson, M. I., Barnes, P. J., Russell, R. E. K., Nicolau, D. V., Ramakrishnan, S., Hobbs, F. D. R., & Butler, C. C., on behalf of the PRINCIPLE Trial Collaborative Group. (2021). Inhaled budesonide for COVID-19 in people at high risk of complications in the community in the UK (PRINCIPLE): a randomised, controlled, open-label, adaptive platform trial. Lancet, 398(10303), 843-55. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(21)01744-X

- Mangin, D., & Howard, M. (2021). The use of inhaled corticosteroids in early-stage COVID-19. Lancet, 398(10303), 818-19.