The Kai Tiaki Nursing Journal, established in 1908 by Hester MacLean (later Matron-in-Chief), has long been a way for nurses to communicate professionally.1

Over the years the journal has had a variety of names: Kai Tiaki The Journal of the Nurses of New Zealand (1908-1930);2 New Zealand Nursing Journal (Kai Tiaki) (1930-1994); and Kai Tiaki Nursing New Zealand (1994 to present)3.

Media images have prevailed of nurses as “young, eager to please, and without the appearance of wisdom”;4 or as angels of mercy or heroines or as overly sexualised.5 This analysis of how advertisers promoted their products to nurses through the pages of the journal provides an insight into the issues nurses faced between 1908 and 2009.

The social constructionist perspective places this advertising against a backdrop of some key national events, thus challenging conventional perspectives6 and appreciating the progressive nature of social problems over time through a different lens.7 Part one analyses the first 50 years from 1908-1958 and part two analyses 1959-2009. (Part two will be published in the December/January issue – Ed.)

Method (part one):

Each issue from January 1, 1908, to November 1, 1947, was thematically analysed in either digital or print form.2 And each issue in 1958 – the journal’s golden jubilee year – was analysed. The total number of issues analysed was 259.

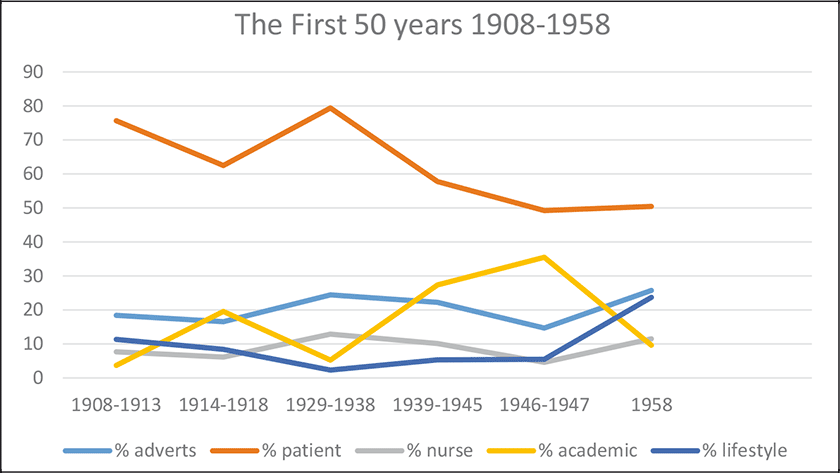

Two themes emerged: the nurse as a wellbeing advocate (1908-1928) and the nurse as servant of the state (1929-1958). Total number of pages; percentage of pages devoted to advertising; special features; and the number of individual adverts under each classification were all counted, cross checked and collated on an Excel spreadsheet under the following categories:

- Patient benefits: eg, devices and supplements

- Nurse benefits: eg, uniforms and self-care items

- Academic activities: eg, textbooks and courses

- Lifestyle items: eg, leisure activities and non-nursing clothing

The tiny number of job adverts and professional notices scattered throughout each journal – estimated at less than one per cent of each issue – were excluded.

Results

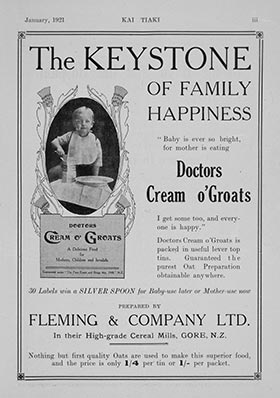

Advertising was present from the first issue. However, the placement, look and feel of these advertisements changed through the years. Product or location photographs were used from January 1914, and photographs of people appeared in January 1921. An image of a cherubic- looking child was repeated through many issues.

The nurse as wellbeing advocate (1908-1928)

Until 1918, advertising took up 16-18.5 per cent of the total journal, with most (75 per cent) focused on patient wellbeing. Key nursing issues in the first decade of the journal included a proposal to form a trained nurses association (1908), the first registration of two Māori nurses in 1910 who went to work in the “Native Health Department”, and a small pox outbreak (1913). While this outbreak, introduced by a Mormon missionary, killed 55 Māori8 it only rated a short comment in the journal: “Small pox is among the native race. It is not of a severe type…”9

In the editorial in the same issue, concern was expressed at the lack of preparedness of nurses for a war or pestilence, with disease the war nurses were fighting. The editor suggested setting up an Army reserve unit to solve the problem of contagious diseases. Given the COVID-19 pandemic more than 100 years later, this is still highly relevant. Despite this concern, no adverts mentioned disinfection or ways to minimise disease transmission.

Adverts placed nurses at the centre of infant nutrition decisions and convalescence supplements. Bonny babies and happy patients apparently derived their health from “winecarnis”, a meat and wine broth, or a petroleum-based emulsion used in Britain and “all British colonies” for “consumption, diarrhoea and wasting disease”.10

Nurses influenced the purchase of medical supplies and drugs as these items were heavily advertised. Some adverts had an education role – one warned of the dreaded “milk clot” which formed in an infant’s stomach if they were not fed the correct milk.11

Against this rather benevolent view of child wellbeing there was a high-profile gruesome event in 1923 – the hanging of baby farmer Daniel Cooper.12 However, the editorial following this national event was devoted to the inappropriate use of the word “nurse” by other professions, rather than social issues such as unwanted pregnancies.13

The pre-WW1 (1908-1913) period had very few adverts (7.7 per cent) for ways nurses could improve their work life. One advert for a nurse’s “chatelaine” or leather pouch, “fitted with the best British made instruments”14 stood out as being of its time.

During WW1 (1914-1918), patient-related adverts dropped to 59.3 per cent, with a rise in adverts aimed at nurses’ benefits at 27.4 per cent. This was possibly due to an increased social appreciation of the value of nurses during wartime. One 1916 issue contained an advertisement targeting “run down nurses” and another noting ample supplies of French and Spanish wines, champagnes and “invalids port”.

Clinical education and state exam preparation featured in each issue, with conditions such as sepsis, consumption, scarlet fever, and neurasthenia examined. In 1909, “kataphoresis” was presented as a new treatment for medicine delivery, with the use of electricity for muscular and rheumatic complaints. Pre-WW1 academic/educational advertising was minimal (3.71 per cent) and only slightly increased during WW1 (5.21 per cent). It peaked in 1916 at 9.28 per cent, but had dropped to zero by 1918.

Women’s rights

Increasing political awareness and women’s rights became apparent during this time, including suffrage, fulfilment outside of marriage and advancement of education.16 This new social freedom and a life away from nursing is hinted at, with lifestyle adverts increasing to about 11-12 per cent of all adverts. Items such as a grand piano, a double bed, the previously mentioned alcohol15 and non-work clothing featured.

However, by the start of the Great Depression in 1929, the lack of discretionary funds also seemed to have an impact on the adverts for nurses, with only 2.3 per cent lifestyle advertising in the ensuing decade. Some issues actually contained no adverts at all, suggesting times were hard for all, including the advertisers.

An ongoing concern around WW1 was the lack of a coordinated nursing war effort or recruitment. As Matron-in-Chief, Maclean asked interested nurses to write to her directly, rather than “bother” the Ministry of Defence. There was concern that soldiers were suffering because of the lack of New Zealand nurses to care for them. Preventable deaths occurred from pneumonia, as Arab nurses did not “nurse after sun down, and the critical time [for pneumonia] is after sunset”.17 Of note, St John and the Red Cross were working independently of the Government sending nurses to war. While a salary of one pound a week and board was recommended, “it was considered… that patriotism should lead a nurse to accept little or no salary”.18

Subtle patriotic propaganda in adverts was used, such as one featuring a photo of a soldier on a horse in the desert. The advert offered a discount on dental work to nurses; however no mention of the war or soldiers was made.19

By October 1918, adverts for patient benefits had decreased by 20 per cent and those for nurse benefits had increased threefold, alongside an increase in articles about treating war injuries. Sadly, the journal also highlights the situation post-WW1 for New Zealand nurses who were demobilised from the Queen Alexandra Reserves and the Army Territorial Service. They received a small gratuity, which was half the amount the regular force nurses received, and were abandoned in London with no lodgings or opportunities to find work. This was in stark contrast to their British counterparts, who received generous paid leave of up to two months, with secure work and accommodation.20

The influenza pandemic

The influenza pandemic (1918-1919) was not mentioned in any advertising. However, an editorial comment noted the number of doctors and nurses who succumbed, and the schoolchildren caring for the sick. This six-week outbreak killed 9000 New Zealanders, more Māori succumbing at seven times the rate of non-Māori. Exact numbers for Māori cannot be confirmed, however, as the 1916 census did not accurately reflect Māori population at the time, due to the boycott of the census by Waikato Māori.21

Some adverts seemed quite frivolous during this time, such as one in January 1919 advertising hair treatments of “singeing”, “staining”, as well as “non-rustable corsets”.

The nurse as a servant of the state (1929-1958)

This period heralded significant sociological, cultural and health-care milestones in New Zealand society. The start of the Great Depression in 1929 led to poverty, hardship and high infant mortality rates of four to five per cent. By 1932, unemployed people were rioting22 and the Government recognised that children’s health needed improving.23 Children were dying in infancy from diphtheria, polio and gastroenteritis.24 Children’s health camps were established, building on the work of Plunket, founded in 1907, and, from 1929, they were funded partially by health stamps. The first health stamp was printed in 1929 to “help stamp out tuberculosis”. This first stamp had an image of a newly graduated nurse and the purpose was to raise money for children’s health camps.25 The November 1929 issue was devoted to tuberculosis, with three articles, along with a discussion on public health work.

Not all was grim however, as by 1934 adverts for holidays and textbooks appeared for the first time.

When war was declared in September 1939,26 nurses needed permission to travel, due to a considerable nursing shortage. St John and the Red Cross set up voluntary nursing aid (VAD) training, coordinated by the Nursing Council, which had been established in 1938. Some of these nurses and VADs went on to work for the Armed Forces.27

The establishment of the Māori Women’s Welfare League in 1951, aimed to address disparities in health care, which were beginning to be recognised, such as immunisation rates, tuberculosis and family planning.28

The most significant medical event at the end of this era was the first open heart surgery, performed on September 3, 1958 at Green Lane Hospital.29

Articles over this time focused on nurses being public servants, reaching out into their communities and working with schools to improve the health of the nation.

The image of the benevolent nurse providing advice on products such as wound care items or infant formula increased during the Depression and pre-WW2 years, with 79.4 per cent of adverts related to patient benefits. Academic and lifestyle advertising combined was less than eight per cent, with some editions having no adverts in either category.

In contrast to the years before 1929, advertising for nurse benefits decreased to an average of 12.9 per cent, with the lowest level of 5.68 percent in 1934.

During WW2 (1939-1945), patient-centred adverts reduced by 20 per cent to 57.85 per cent and academic advertising increased from virtually zero to an average of 27 per cent. While lifestyle advertising remained low – at between one to eight per cent of the total adverts – there was a significant increase to 11 per cent of total adverts in 1942. This was due to adverts encouraging nurses to make war savings or buy war bonds. Nurses could also send away for product samples to recommend to patients.

The first advert for makeup was seen in 1930, also the year the journal became bimonthly. By 1935, adverts for glamorous high-heeled shoes and golf shoes appeared and then in 1936 dancing shoes were advertised.

Despite the measles epidemic of 1938, which claimed the lives of 212 Māori and 163 Europeans,30 no content reflected this. It seemed that by 1938, New Zealand was breathing a sigh of relief that the threat of war was over and life was continuing as normal. This absence of discussion on the growing political crisis in Europe continued right up to the August 1939 issue, published just before WW2 was declared. However, by the following issue, articles advised on how to sign up for service and how to practise preparing for an air raid, and gave information about London and the role of casualty clearing.

From 1940, nurses could work as occupational health nurses, possibly to help manage the large numbers of women employed in factories for the war effort.

In the immediate post-war period – 1946-1947 – the total space given to adverts had dropped significantly, with most issues containing three to four pages of adverts, compared to 10 to 12 pages previously, The journal was also smaller, at around 24 pages, possibly because it was now published monthly. Patient-related adverts still accounted for just over a half of all adverts at 50.44 per cent, compared to the peak of the interwar/depression areas of 79.38 per cent. Educational advertising had increased to 35 per cent, compared to a low of five per cent during the depression years.

By 1957, the journal had become more glossy and was back to being published bimonthly, apart from the golden jubilee issues in 1958.

In 1958, advertising accounted for 25 per cent of the journal, with over half still devoted to patient benefits. Job adverts were prominent at almost 10 per cent, with most of those being for agency positions in the United Kingdom. Lifestyle adverts accounting for just over 20 per cent, with ads for flying holidays and typewriters now included.

Conclusion

Over the 50 years of this analysis, the trend was away from patient-centred advertising towards increased education and lifestyle advertising. The total proportion of advertising remained fairly constant, even though the number of pages and issues published changed. The two key increases over this time were in academic/educational advertising during the two world wars and a reduction in advertising content directed at patient needs. By 1958, advertising in the the journal was less about patients and more about nurses’ professional and lifestyle needs.

Acknowledgement: I am grateful for the voluntary assistance provided by history graduate Nyle Maddocks-Hubbard, who helped with the collection and cross-checking of data in both electronic and print format.

Wendy Maddocks, RN, DHlthSc, BA, MA, is a lecturer in the School of Health Sciences at the University of Canterbury.

References

- Ministry for Culture and Heritage. (n.d.). The world’s first state-registered nurse.

- National Library of New Zealand. (n.d.). Kai Tiaki – the Journal of the Nurses of New Zealand

- New Zealand Nurses Organisation.(n.d.). Kai Tiaki Nursing New Zealand.

- Lusk, B. (2000) Pretty and powerless: Nurses in advertisements, 1930–1950. Research in Nursing & Health, 23(3), 229-36.

- McNally, G. (1995). Combatting negative images of nursing. Kai Tiaki Nursing New Zealand, 15(10), 19.

- Burr, V. (2015). Social constructionism (3rd ed.). Routledge: London.

- Weinberg, D. (2014). Contemporary social constructionism: key themes. Philadelphia: Temple University Press.

- Ministry for Culture and Heritage. (2019). Smallpox epidemic kills 55.

- Editorial. (1913). Nursing Reserve. Kai Tiaki The Journal of the Nurses of New Zealand, 6, 89-90.

- Angier Chemical Coy. Advert Angiers Emulsion. (1910). Advert. Kai Tiaki, The Journal of the Nurses of New Zealand, III(1).

- Keen Robinson and Co, Robinsons ‘patent’ Barley. (1928). Advert. Kai Tiaki, The Journal of the Nurses of New Zealand, Oct, 201.

- Ministry for Culture and Heritage. (2016). Baby-farmer Daniel Cooper hanged.

- Editorial. (1923). The Terms “Nurse” and “Probationer”. Kai Tiaki, The Journal of the Nurses of New Zealand, XVL(July 3), 97.

- Sharland & Co Ltd. (1909). Nurses’ Leather Wallets (Advert). Kai Tiaki, The Journal of the Nurses of New Zealand, 11(3), IV.

- A. D. Kennedy and Co. (1916). Advert. Kai Tiaki, A Journal for the Nurses of New Zealand, p183.

- Jellie Rev. (1911). The Progress of Woman. Kai Tiaki, The Journal of the Nurses of New Zealand, IV(April 2), 61.

- Anonymous. (1915). Active Service. Kai Tiaki, The Journal of the Nurses of New Zealand, VIII(1), 13.

- Anonymous. (1915). Salaries for Nurses serving during the war. Kai Tiaki, The Journal of the Nurses of New Zealand, VIII(January 1), 25.

- Anglo American Dental Dentistry. (1917). Kai Tiaki, The Journal of the Nurses of New Zealand, X(1), 60.

- Anonymous. (1919). Demobilisation. Kai Tiaki, The Journal of the Nurses of New Zealand, XII(July 3), 116.

- Rice, G. (1918). New Zealand’s worst disease-disaster: 100 years since the 1918 influenza pandemic.

- Museum of New Zealand. (n.d.). Social welfare and the State, Great Depression.

- Te Ara The Encyclopedia of New Zealand. (n.d.). New Zealand infant mortality rate, 1862–2017.

- Te Papa Museum of New Zealand. (n.d.). Social welfare and the state, Children’s health.

- New Zealand Post. (n.d.). 1929 Health.

- Editorial. (1939). Kai Tiaki: The Journal of the Nurses of New Zealand. Sept 2.

- Stout, T. D. M., (1958). Medical Services in New Zealand and The Pacific. Wellington: Historical Publications Branch.

- New Zealand History. (n.d.). Māori Women’s Welfare League established.

- New Zealand History. (n.d.). First open-heart surgery in New Zealand.

- Te Ara The Encyclopedia of New Zealand. (n.d.) A timeline of epidemics in New Zealand (PDF, 144KB).