LEARNING OBJECTIVES

After reading this article, you should be able to:

- describe basic asthma pathophysiology, asthma triggers and other factors that contribute to poor respiratory health

- understand the recommended New Zealand guidelines for management of asthma in children, and in adolescents and adults

- describe the appropriate use of AIR and SMART therapy

- identify asthma management strategies that can be used to address the inequitable outcomes that persist for Māori and Pacific peoples

- access resources to ensure you can demonstrate good inhaler technique and provide patients with asthma education that is appropriate for them.

Introduction

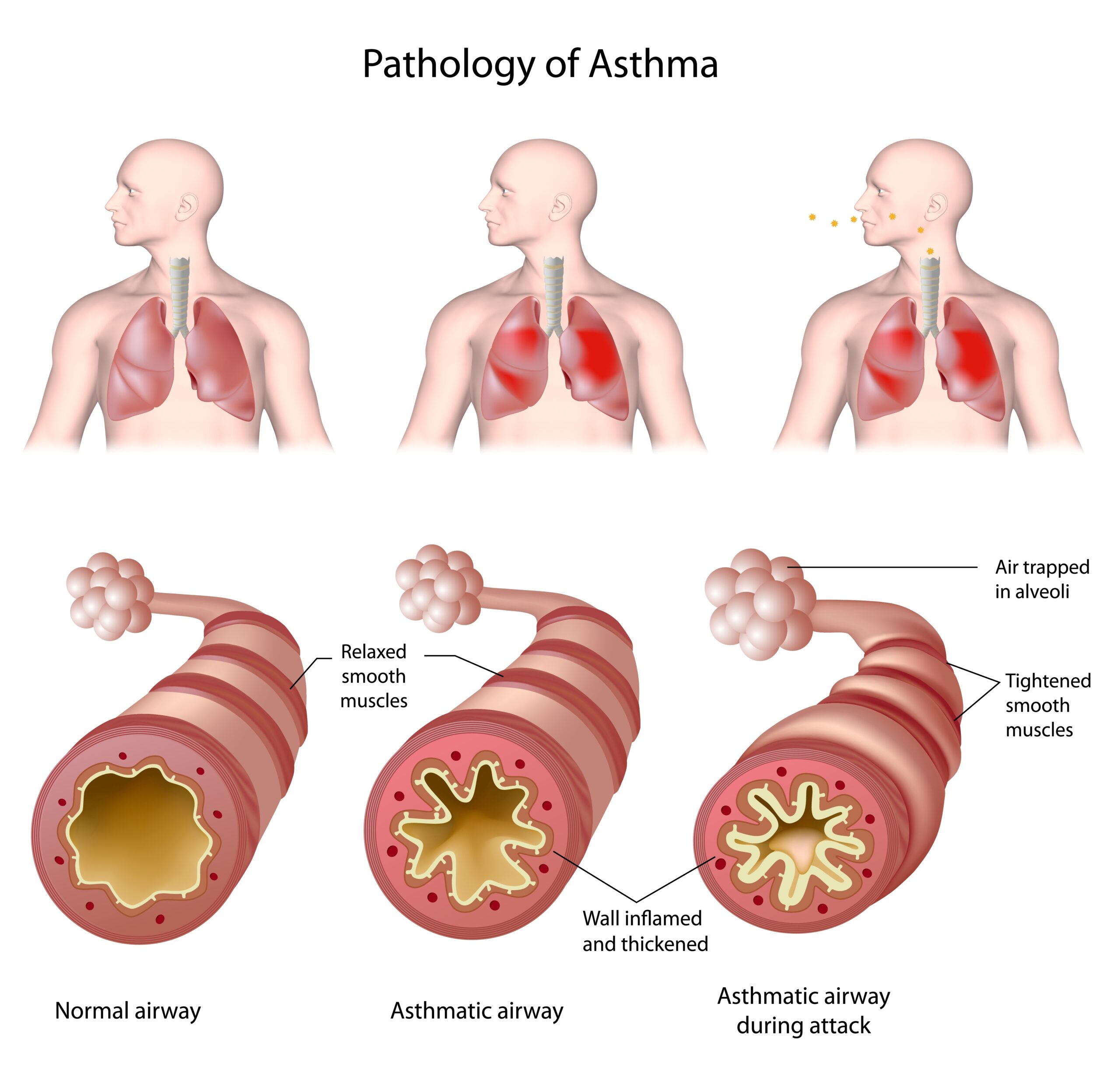

Asthma is characterised by a reversible narrowing of the airways due to tightening of muscle in the wall of the airway, and by inflammation and swelling of airway mucosa (see Panel 1 below). Airway narrowing and excess mucus production lead to a variety of symptoms and signs including wheezing, cough, shortness of breath and observed breathing difficulty.

Key points

- Asthma prevalence, hospitalisations and deaths remain markedly high among Māori and Pacific peoples.

- Māori with asthma are less likely to be prescribed inhaled corticosteroids (ICS), have an action plan or receive adequate education.

- Treatment with a short-acting beta2 agonist (SABA) alone is not recommended for adults and adolescents as it increases exacerbation risk.

- AIR therapy with combined ICS/fast onset long-acting beta2 agonist (LABA), initiated from first diagnosis, is the preferred treatment for adults and adolescents with asthma.

For nurses to consider

- Strategies to achieve equitable health outcomes include improving patient/whānau knowledge about asthma and providing care that is appropriate, acceptable and effective.

- Inadequate inhaler technique, along with poor adherence, are the two most common reasons for sub-optimal asthma control.

Asthma is a major public health problem in New Zealand, affecting up to 20 per cent of children and adults. According to a recent report, the prevalence of asthma in this country has not significantly changed from 2000-2019 and asthma hospitalisations have even declined slightly. New Zealand mortality rates, though, while reaching a low point in 2010, have increased, hitting a high point in 2017 of 2.5 deaths per 100,000 people.1

Although overall asthma prevalence has stayed generally static, this is not the case for Māori and Pacific peoples, for whom asthma remains more prevalent than in non-Māori and non-Pacific peoples, and hospitalisation and death due to asthma are unacceptably high. These disparities that have been persistent in New Zealand for years now.1

In 2019, asthma hospitalisations for both Māori and Pacific peoples were more than three times those of New Zealand Europeans (rate ratios 3.24 and 3.22, respectively), with the ratio for Māori increasing markedly from that reported in 2018. Asthma mortality rate ratios over 2012-2017 followed the same pattern: respectively, Māori and Pacific peoples had rates 3.36 and 2.76 times those of New Zealand Europeans.1

Inadequate inhaler technique, along with poor adherence, are the two most common reasons for sub-optimal asthma control.

Despite awareness of these differences, the level of care Māori and Pacific peoples receive does not match their disease burden. And, for a number of years, studies have documented disparities in the two main aspects of asthma management, namely:2

- asthma education, knowledge and self-management, and action plans

- asthma medication.

Māori with asthma are less likely to be prescribed inhaled corticosteroids (ICS), have an action plan or receive adequate education, and face other major barriers to good asthma management such as poor access to care and services that do not meet their needs. These issues are likely to be similar for Pacific peoples.3

To reduce disparities, health professionals need to ensure that Māori and Pacific patients receive appropriate medication. They also need education about asthma to improve their knowledge and empower them to self-manage their condition — nurses have a role in ensuring this is an ongoing component of asthma care.

Panel 1: Quick refresher on asthma

Asthma is caused by a combination of genetic and environmental factors. For many people, it occurs in combination with allergic conditions, such as eczema or allergic rhinitis (hay fever), or they may have relatives with these conditions.

There are different types of asthma, but the underlying airway narrowing is a result of:

- bronchoconstriction, due to contraction of smooth muscle

- airway wall thickening, due to swelling of the lining (inflammation)

- increased mucus production.

Symptoms

Wheezing, shortness of breath, cough, chest tightness, difficulty breathing out and increased mucus production.

Triggers

Infections, allergens (eg, pollen, dust mites, pets), smoke, exercise, weather (eg, cold or humidity), chemicals (eg, perfumes, cleaning products, aerosol sprays) and stress.

Medicines, such as beta-blockers (including in eye drops), non-steroidal anti-inflammatory agents (NSAIDs) and aspirin, can also trigger asthma. NSAIDs and aspirin can often be taken safely as they do not trigger asthma in everyone.

Angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors frequently cause a cough that can be confused with asthma, and in some people with unstable airways, these drugs may trigger an asthma attack.

People should be encouraged to identify their asthma triggers.

How can nurses and other health professionals help?

People with well-controlled asthma:

- have no or minimal symptoms, both during the day and at night

- need little or no as-needed medication

- can participate in physical activities without restriction

- have normal or near-normal lung function

- avoid serious asthma exacerbations, including the need for hospitalisation.

Effective self-management of asthma requires patients and their whānau to have a good understanding of asthma and how it is managed. People who are unaware of what good asthma management looks like are more likely to normalise and accept sub-optimal asthma control. Nurses have a valuable role in improving this understanding, supporting patients/whānau and improving outcomes by embedding asthma education into their practice.4

Asthma education should be tailored to the patient/whānau. Poor asthma literacy is associated with reduced self-efficacy and decreased use of asthma medicines, and is likely to contribute to asthma disparities. Always ensure asthma information is communicated in a way that aligns with patient/whānau health literacy, and check they understand the information.4

The Health Quality & Safety Commission’s “Three steps to meeting health literacy needs” has been developed to improve health outcomes for Māori and to maintain cultural safety. It provides a useful framework for assessing patient/whānau asthma knowledge, reinforcing existing knowledge and correcting gaps in understanding or misconceptions.

Once the health professional has ascertained the patient’s level of asthma knowledge, this can be built on step by step. Focus on expanding one aspect of asthma understanding at every point of contact.4

When discussing asthma with patients, be sure to use everyday language, not jargon, and try to adopt terms the patient or their whānau have used, thereby building a common language. For example, use “puffer” if the patient refers to their inhaler in this way.

When discussing asthma with patients, be sure to use everyday language, not jargon.

Avoid overloading patients with too much information at a time – start with the most important point. Be creative when trying to increase understanding – use illustrative analogies, and “what if” scenarios where patients describe how they would manage a situation likely to result in asthma. Offer targeted resources for patients to take away (check with asthma service providers for availability of these).

A map providing a directory of local asthma societies with contact details is available from the Asthma and Respiratory Foundation NZ. The foundation has a variety of asthma resources — some in te reo Māori, and in Samoan, Tongan and Chinese languages.

Asthma action plans

Everybody with asthma should be encouraged to have a personalised asthma action plan. These guide patients on when and how to adjust treatment over the short term in response to worsening symptoms, and when to get additional medical care. They have been shown to improve health outcomes and reduce hospitalisations.3,4

Plans should be updated annually, and be appropriate for the patient’s treatment level, asthma severity, health literacy, culture and ability to self-manage. Nurse practitioners have an important role in preparing action plans, while non-prescriber nurses can go through an action plan with the patient to ensure they understand it.

Action plans come in a range of formats – written, pictorial, electronic, app – with adult and child asthma action plans available in te reo Māori, Samoan, Tongan and English. They can be downloaded from the Asthma and Respiratory Foundation website, or ordered in print, and are available on the My Asthma App (see Asthma resources at the end of this article).

The foundation also provides adult asthma action plans as interactive PDFs; these can be customised by the health professional and emailed to the patient.

Action plans may be based on symptoms with or without peak-flow measurements and are either three or four-stage, depending on both patient and health professional preference. The four-stage plan has an extra step giving patients the option of increasing the dose of ICS up to four-fold, by increasing the frequency of use and/or the dose.3

Asthma management is a cycle of ongoing assessment, treatment and review. When discussing asthma management with patients/whānau, nurses should make sure the patient’s own personal goals are included and documented as shared goals of care.

Guidelines reviewed and updated in 2020

The Asthma and Respiratory Foundation published new asthma guidelines in 2020, which include recommendations for improving care for Māori and Pacific peoples.3 There are no longer separate guidelines for adults and adolescents (people aged 12 and over), as treatment is the same.

The guidelines for children have also been reviewed and updated.5 These are based on recommendations by the Global Initiative for Asthma (GINA).

The GINA Assembly includes members from 45 countries. Every year, they publish a report6 and a pocket guide,7 to provide a comprehensive international approach to management of asthma and to provide clear guidelines and feasible tools for clinical practice, using a strong evidence base.

In 2019/20, there were major changes to GINA’s recommendations for asthma treatment, which now advocate the use of AIR/SMART therapy, following a large, double-blind study investigating this method.

This therapy combines two medicines, budesonide and formoterol, in a single inhaler. Budesonide is an inhaled corticosteroid (ICS), which has anti-inflammatory actions.8 Formoterol is a fast-onset, long-acting beta2 agonist (LABA) that causes bronchodilation.8 The inhaler can be used either as needed for symptom relief (AIR – anti-inflammatory reliever therapy), or regularly for symptom prevention plus as needed (SMART – single maintenance and reliever therapy).

These recommendations apply only to people with asthma, not to people with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD).

Why were recommendations changed?

The previous recommendations dated back many years and were based on the belief that mild asthma was primarily bronchoconstriction. However, we now know that airway inflammation is found in most people with asthma, even if they only have symptoms intermittently.

Clinical studies have shown that anti-inflammatory treatment with an ICS significantly reduces the frequency and severity of asthma symptoms, and markedly reduces the risk of experiencing, or even dying from, an asthma attack.

Strong evidence shows that, although short-term relief from symptoms of bronchoconstruction is achieved with short-acting beta2 agonist (SABA)-only treatment, this does not protect from severe exacerbations. In fact, regular or frequent use of SABA treatment (salbutamol or terbutaline) increases the risk of exacerbations, worsening airway inflammation and lung function, and increasing allergic reaction.

The GINA report states that overuse of SABA treatment (eg, three or more canisters per year) is associated with an increased risk of severe exacerbations, and 12 or more canisters per year is associated with increased risk of asthma-related death.6

The new recommendations aim to:

- reduce the risk of serious exacerbations

- reduce the pattern of people depending on SABA-only treatment to manage their asthma

- provide consistent treatment plans across the whole range of asthma severity.

Are you familiar with ‘AIR’ therapy?

Anti-inflammatory reliever (AIR) therapy is the use of a combination budesonide/formoterol inhaler as a reliever medication. It can be used either only as needed, or regularly plus as needed. This approach includes and extends the “single combination ICS/LABA inhaler maintenance and reliever therapy” (SMART) approach previously recommended. The AIR regimen and the use of asthma action plans have been shown to improve outcomes for Māori.3

- AIR therapy requires an ICS in combination with a fast-onset LABA. In New Zealand this is budesonide/formoterol (formoterol and eformoterol are alternative names for the same medication).

- Other combinations of ICS/LABA should not be used in this way.

- When using budesonide/formoterol as maintenance and reliever therapy, a SABA reliever should not be prescribed.

- For people using a combination ICS/LABA maintenance inhaler that is not budesonide/formoterol, a SABA reliever should still be used.

- The budesonide/formoterol reliever combination should not be prescribed in addition to other ICS/LABA preparations.

- A LABA should not be prescribed without an ICS for people with asthma.

- Note that the budesonide/formoterol 400µg/12µg formulation should not be used as a reliever, due to the potential for use of inappropriately high ICS and LABA doses.

AIR therapy in New Zealand

The only ICS/fast-onset LABA combination currently available in New Zealand is budesonide/formoterol, and only the dry powder inhalers are approved for reliever use. A budesonide/formoterol pressurised metered dose inhaler is available, but this would represent an off-label prescription.

What has changed for treatment of adults and adolescents?

Starting asthma treatment with a SABA (ie, salbutamol or terbutaline) alone is no longer recommended. Instead, it is recommended an ICS be initiated from first diagnosis.

This can be done either by introducing AIR treatment or by using traditional ICS/SABA therapy (see later). One of the risks of traditional ICS/SABA therapy is that people do not use the ICS and rely solely on the SABA. AIR therapy removes this risk as the ICS is included in the reliever treatment as well as maintenance treatment.

Stepwise AIR-based algorithm using budesonide/formoterol 200µg/6µg:3

The stepwise approach to asthma management entails a patient stepping up management levels as required to achieve and maintain asthma control and reduce exacerbation risk. A step down is considered if symptoms are controlled for three months and the patient is at low exacerbation risk.

Step 1 – one inhalation as required to relieve symptoms to a maximum of six inhalations on a single occasion or a total of up to 12 inhalations daily.8 This results in a similar short-term bronchodilator response to that of a 200µg dose (ie, two 100µg doses) of salbutamol and, in adults and adolescents with mild asthma, reduces the risk of a severe asthma exacerbation by at least 60 per cent compared with SABA reliever alone.

Step 2 – regular maintenance treatment is implemented as either one inhalation twice daily or two inhalations once daily, depending on patient preference. Plus one inhalation as required, to a maximum of six inhalations on a single occasion or a total of up to 12 inhalations daily.8

Step 3 – maintenance treatment is stepped up to two inhalations twice daily. Plus one inhalation as required, to a maximum of six inhalations on a single occasion or a total of up to 12 inhalations daily.8

In adults and adolescents taking maintenance ICS/LABA therapy, budesonide/formoterol used as a reliever reduces the risk of a severe asthma exacerbation by about one-third, compared with using a SABA reliever. Thus, budesonide/formoterol used both as a reliever plus regularly as maintenance therapy is the preferred treatment for patients with moderate to severe asthma.

Stepwise ICS/SABA-based algorithm for asthma management

The current recommendations are:3

Step 1 – introduce standard-dose ICS as maintenance treatment, plus a SABA as needed.

Step 2 – use standard-dose ICS/LABA as maintenance treatment, plus a SABA as needed.

Step 3 – use high-dose ICS/LABA as maintenance treatment, plus a SABA as needed.

Note the recommendation that if a severe exacerbation of asthma occurs, consider switching to AIR therapy.

ICS doses

For most people, most of the clinical benefit is obtained with low-dose ICS. Some people will need standard-dose ICS if their asthma is not well controlled with low-dose ICS, but concordance and inhaler technique should be checked first. A few will need high-dose ICS.

When an ICS is initiated as maintenance therapy together with a SABA reliever, a standard dose of ICS should be used. The recommended standard daily doses of the different ICS preparations for adults are:3

- beclomethasone dipropionate 400–500µg/day (Beclazone*)

- beclomethasone dipropionate extrafine (Qvar*) 200µg/day

- budesonide 400µg/day

- fluticasone propionate 200–250µg/day

- fluticasone furoate 100µg/day.

*Subsidised brands at time of publishing

What if optimal inhaled therapy doesn’t work?

Alternative treatments for asthma may include:

- Long-acting muscarinic antagonists – are not subsidised in New Zealand for the treatment of asthma, although tiotropium is Medsafe-approved for add-on maintenance treatment. Note that LAMAs are funded for patients with COPD, and there will be a significant cohort who have coexisting asthma and COPD.

- Montelukast – is a leukotriene receptor antagonist. In New Zealand, it is indicated for adults and children over the age of two for prophylaxis of asthma or relief of allergic rhinitis (seasonal or perennial). Montelukast should be considered as add-on therapy when control is not achieved with optimal standard treatment; for everyone with respiratory conditions exacerbated by aspirin; and may be useful in exercise-induced asthma or people with coexisting rhinitis.3

Note the precaution around neuropsychiatric side effects with montelukast.9 Patients taking montelukast should be advised to contact a health professional if they experience sleeping problems, unusual dreams, changes in behaviour, hallucinations, anxiousness or agitation, confusion or suicidal thoughts.10

- Mast cell stabilisers – sodium cromoglicate and nedocromil inhalers are approved for use in mild asthma; however, the supplier, Sanofi, has discontinued supply in New Zealand and these inhalers are no longer available. Patients should be managed on alternative treatments, in line with current asthma guidelines.11

- Other treatments – include oral corticosteroids, theophylline, azithromycin and monoclonal antibodies, many of which will only be used following specialist review.

Children aged under 12

The New Zealand Child Asthma Guidelines were updated in June 2020.5 As well as prescribing recommendations, these guidelines include important ways that nurses and other health professionals can help children with asthma (see Panel 2 below).

The guidelines also summarise the medication approaches for children of different ages (see later). The goal is for all children to use an inhaler device that is appropriate for their development, including consideration of whether a spacer or mask is appropriate.

It is important that children’s treatment includes regular review to allow step-up or step-down through treatment options as appropriate for symptom control.

Children aged one to four years – who wheeze are considered in a different way from children aged five to 11, as many preschool children with post-viral wheeze do not have asthma or do not go on to develop asthma.

The current recommendations are:5

Step 1 – SABA reliever alone (one to two puffs when needed)

Step 2 – add maintenance low-dose ICS

Step 3 – add montelukast

Step 4 – refer to a paediatrician.

Note that if SABA, ICS and montelukast are insufficient, step 4 is referral to a paediatrician. This means that LABAs are not part of the routine management of wheeze or asthma in this age group.

Children aged five to 11 years – assessment of inhaler technique and adherence to treatment remains key in this age group.

The current recommendations are:5

Step 1 – SABA reliever alone (one to two puffs when needed)

Step 2 – add maintenance low-dose ICS

Step 3 – add LABA

Step 4 – increase to standard dose of maintenance ICS/LABA; add montelukast; consider referral to a paediatrician

Step 5 – consider high-dose ICS/LABA; refer to a paediatrician.

At Step 5, the child will likely be having frequent oral steroids and should definitely be referred to a paediatrician.

Currently, there is insufficient evidence to recommend SMART as first-line therapy in children aged 11 years and younger. However, SMART using budesonide/formoterol 100µg/6µg may be considered on specialist advice, in select children aged five to 11 years, who are poorly controlled at steps 3 to 5.

Panel 2: Top 10 ways health professionals can help childhood asthma (apart from prescribing medicines)

| Ambulance | Influenza vaccine |

|---|---|

|

|

| Relationships | Health literacy |

|

|

| Smoke exposure | Concordance |

|

|

| Housing | Asthma action plan |

|

|

| Income | Access |

|

|

Source: New Zealand Child Asthma Guidelines

Review treatments with your patients

Asthma attacks can be very serious, even fatal. They are more common and more severe in people with poorly controlled asthma and in high-risk people, but they can occur in anyone with asthma. It is useful for nurses to know that high use of SABA inhalers indicates poor asthma control and increases the risk of severe exacerbation and mortality.

Many people will still be using SABA-only treatment for mild asthma. In 2018, over two million salbutamol inhaler devices were dispensed in the community setting in New Zealand,12 making it the eighth most dispensed Pharmac-funded medicine.13

Nurses should ask people how much SABA they are actually using – inhalers tend to get lost or given to someone else, and some people will want to have inhalers in different rooms of the house, or in the car or sports bag, for example.

Check patients’ inhaler technique at every visit, and before starting any dose increase.

Also be aware that many people on ICS/SABA therapy don’t collect their ICS prescriptions, and may rely on high doses of SABA to relieve symptoms. AIR/SMART therapy may be beneficial for these people, as having one combined ICS/LABA inhaler for as-needed use, and for regular use if required, not only ensures that the ICS is taken more regularly but also provides safer treatment right from the start.

Another important reminder is that people with asthma should continue taking all prescribed asthma medications during the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic.

Inhaler technique

Worldwide, it is estimated that up to 80 per cent of people do not use their inhaler correctly, and at least 50 per cent do not use their maintenance medications as prescribed.7 Inhaler technique remains critical to optimal therapy, no matter which inhaler device is being used.

Inadequate technique is among the most common reasons, along with poor adherence, for sub-optimal asthma control,3 so it is a good idea for nurses, doctors and pharmacists to routinely check patient technique at each visit. Good technique must be ensured before any escalation in treatment.

Patients can access videos on correct inhaler technique on the National Asthma Council Australia website. If a patient has persistent difficulty with their technique, consider switching to a different inhaler. The UK’s National Institute for Clinical Excellence has a patient inhaler decision aid that contains information to help adults with asthma, and their health-care professionals, when discussing options for inhaler devices.

Spacers should be supplied free of charge to patients; they can be ordered, fully subsidised, on a practitioners supply order.

People who use a metered-dose inhaler may benefit from using a spacer, as many will find it challenging to coordinate their inhaler use with their breathing. Spacers help deliver the medicine directly into the lungs, rather than the mouth and throat, thus markedly increasing medicine effectiveness.

Spacers also reduce local side effects from ICS inhalers, such as hoarseness, throat irritation and oral candidiasis – but remind patients to still rinse their mouth after ICS use.

Every asthma patient should be offered a spacer, which should be supplied free of charge; they can be ordered, fully subsidised, on a practitioners supply order. Instruct patients to wash spacers weekly with warm water and detergent, and to let them air dry to reduce static charge.

Reducing the asthma burden for Māori and Pacific peoples

All health professionals have a role in improving health outcomes and health equity, as well as delivering high quality, effective asthma care. Nurses, other health professionals, and health services, can achieve this by:2,3,4

- Ensuring their own knowledge of asthma and clinical practice is up to date and consistent with the current evidence-based guidelines.

- Supporting all health professionals to develop culturally safe skills for engaging with Māori and Pacific peoples and their whānau.

- Building and maintaining long-term, high-quality, trusting relationships with patients.

- Regularly undertaking clinical audits to determine if care is consistent with the current guidelines and to identify ethnic disparities in care. Strategies that address disparities and improve asthma care should then be developed and implemented, and a follow-up clinical audit undertaken to assess their effectiveness.

- Ensuring access for all patients to individualised, understandable, appropriately formatted asthma action plans, including provision of updated electronic access to asthma plans for whānau, community health workers and schools.

- Being aware of local Māori health providers who have asthma programmes, and asthma services that employ Māori and Pacific staff, and referring people to these services when appropriate.

- Using every opportunity to increase patient/whānau knowledge about all aspects of asthma and its management, providing information that is appropriate, acceptable and effective for Māori. When appropriate, direct patients/whānau to online learning sites that contain useful resources in a variety of media.

- Being mindful of individual, institutional and structural racism when providing health care to Māori and Pacific patients.

What about wider barriers to care?

Research has shown that appropriately designed and delivered health programmes improve Māori health outcomes.2 Māori leadership is needed to develop asthma management programmes that improve access and enable “wrap around” services targeting the wider barriers Māori face in asthma care.3

These barriers include cost and affordability of care, poor access to care and poor quality or discontinuous care, services or approaches not meeting needs, culturally inappropriate services, institutional racism, lack of trust and confidence in the health system, unhealthy indoor environments in high deprivation areas, and increased risk factors such as obesity and smoking.3

Systemic changes will be required to address these wider barriers to care for Māori. A paradigm shift is under way with New Zealand’s health reforms. The role of the newly formed partnership between Te Aka Whai Ora – the Māori Health Authority, Te Whatu Ora – Health New Zealand, and Manatū Hauora – the Ministry of Health is to lead and monitor transformational change in the way the entire health system understands and responds to the health and wellbeing needs of Māori and their whānau.

A central tenet is ensuring everyone has the same opportunities to achieve good health outcomes by creating a fairer, more coordinated and connected health system. It is long overdue.

FURTHER READING

- Best Practice Journal — Asthma education in primary care: A focus on improving outcomes for Māori and Pacific peoples – a two-page summary of key practice points for improving asthma education in Māori and Pacific peoples.

- Medical Council of New Zealand — Our Standards: Cultural Safety lists key documents and resources for health professionals to learn about cultural safety and bias, and examine their practice.

- Health Quality & Safety Commission New Zealand — Three steps to meeting health literacy needs | Ngā toru hīkoi e mōhiotia ai te hauora – a guide for health professionals, to help achieve equitable health outcomes for Māori and maintain cultural safety, reinforcing useful knowledge/skills, building on them and checking how effective the process has been.

- Pacific Perspectives — A review of evidence about health equity for Pacific Peoples in New Zealand – a report describing the health equity issues faced by Pacific families and communities and the barriers and facilitators to accessing health care.

Asthma resources

- The Asthma and Respiratory Foundation has a dedicated page of resources for patients, carers and health professionals, including guidelines, diaries, teachers’ toolkits, educational resources for parents, checklists and asthma first aid posters. Many are downloadable.

- The foundation’s asthma action plans are available in several languages. They can be downloaded or ordered in print.

- The foundation also offers My Asthma App for Android and Apple. This downloadable app allows for an individualised asthma action plan, and provides education on asthma signs and symptoms, triggers, treatment, and medicines, as well as an asthma control test, and helpful contacts and resources.

- Asthma New Zealand has many resources (some downloadable) providing education and support to people with asthma and their whānau, including young people and children.

Courses for clinical learning

- The Asthma and Respiratory Foundation asthma & COPD fundamentals eLearning course – updated in February 2021 and designed for all registered health professionals including nurses, pharmacists, physiotherapists and GPs.

- Asthma New Zealand, nurse education in asthma treatment (NEAT) course – full-day, in-person or online course suitable for nurses, pharmacists, physiotherapists, GPs and other qualified health professionals.

The Asthma and Respiratory Foundation NZ Adolescent and Adult Asthma Guidelines 2020 and New Zealand Child Asthma Guidelines are available on the NZ Respiratory Guidelines website.

More clinical asthma education, including a bulletin, recorded webinar, EPiC dashboard and reflection activities are available at He Ako Hiringa.

Reading this article and reflecting on its content can equate to one hour of CPD time. Nurses can use the Nursing Council’s professional development activities template to record professional development completed via Kaitiaki, and they can then have this verified by their employer, manager or nurse educator.

Helen Cant is a pharmacist prescriber working in general practices in Tokoroa.

Gayle Robins is a freelance medical writer.

References

- Barnard, L. T., & Zhang, J. (2021). The impact of respiratory disease in New Zealand: 2020 update.Asthma and Respiratory Foundation NZ.

- Crengle, S., Pink, R., & Pitama, S. (2007). Respiratory Disease. In Robson, B., Harris, R. (Eds), Hauora: Māori Standards of Health IV. A study of the years 2000–2005(ch. 10, pp. 168-79). Te Rōpū Rangahau Hauora a Eru Pōmare.

- Beasley, R., Beckert, L., Fingleton, J., Hancox, R. J., Harwood, M., Hurst, M., Jones, S., Kearns, C., McNamara, D., Poot, B., & Reid, J. (2020). Asthma and Respiratory Foundation NZ adolescent and adult asthma guidelines 2020: a quick reference guide. New Zealand Medical Journal, 133(1517), 73-99.

- Best Practice Journal. (2015). Asthma education in primary care.

- McNamara, D., Asher, I., Davies, C., Demetriou, T., Fleming, T. Harwood, M., Hetaraka, L., Ingham, T., Kristiansen, J., Reid, J., Rickard, D., Ryan, D., & Turner, J. (2020). New Zealand Child Asthma Guidelines: a quick reference guide. Asthma and Respiratory Foundation NZ.

- Global Initiative for Asthma. (2020). Global Strategy for Asthma Management and Prevention.

- Global Initiative for Asthma. (2020). Pocket Guide for Asthma Management and Prevention (for adults and children older than 5 years).

- New Zealand Formulary. NZF v94.

- Medsafe. (2017). Montelukast – reminder about neuropsychiatric reactions.

- New Zealand Formulary for Children. NZF v94.

- Pharmac. (2020). Nedocromil (Tilade) and sodium cromoglicate (Intal Forte) inhaler: Discontinuation.

- Pharmac. (2020). Official Information Act responses: Asthma inhaler devices dispensed: Number of asthma inhalers dispensed in both the community and hospital settings(2014–2018).

- Pharmac. (2020). Official Information Act responses: New Zealand Pharmaceutical Market: Information about the top 100 medicines prescribed in New Zealand by price and volume.