Gout – a form of inflammatory arthritis – is not a benign medical condition. Not only does it cause debilitating pain and potential long-term erosion of the joint, and is associated with cardiovascular and renal comorbidities, it also has a large impact on the social, psychological and spiritual wellbeing of the affected person and their whānau. Furthermore, there are persistent inequities because of poorly-managed gout in populations that have higher prevalence of this serious condition.

New Zealand has one of the highest prevalences of gout internationally. About 208,000 people, or 5.7 per cent of people aged 20 or older, are identified as having gout, according to 2019 New Zealand data. Gout was identified in 8.5 per cent of Māori, close to twice that of non-Māori, non-Pacific peoples (4.7 per cent) and in 14.8 per cent of Pacific peoples, nearly three times that of non-Māori, non-Pacific peoples. Notably, fewer women than men experience gout, but Māori and Pacific women remain disproportionately affected, compared with non-Māori, non-Pacific women.1

Gout prevalence increases with age. Eighteen per cent of non-Māori, non-Pacific men aged 65 or over are estimated to have gout; however, this proportion increases to 35 per cent for Māori and 50 per cent for Pacific peoples in this age group.1

Belief –”Gout is just an old person’s disease.”

Rates of regular dispensing of preventive gout medicines are very low across all ethnicities – only 36 to 43 per cent of people with gout in 2019 – and worse in young people.1 Māori and Pacific peoples are more likely to be affected by severe gout, early onset gout, tophaceous disease and accelerated joint damage than non-Māori, non-Pacific peoples.2 Additionally, over 2016–2020, they started preventive gout medicine, on average, 10 to 13 years earlier than non-Māori, non-Pacific peoples did.3 However, given their much higher gout disease burden, this time gap may be too narrow, and Māori and Pacific peoples should perhaps be starting their gout preventive treatments even earlier to achieve equitable care.

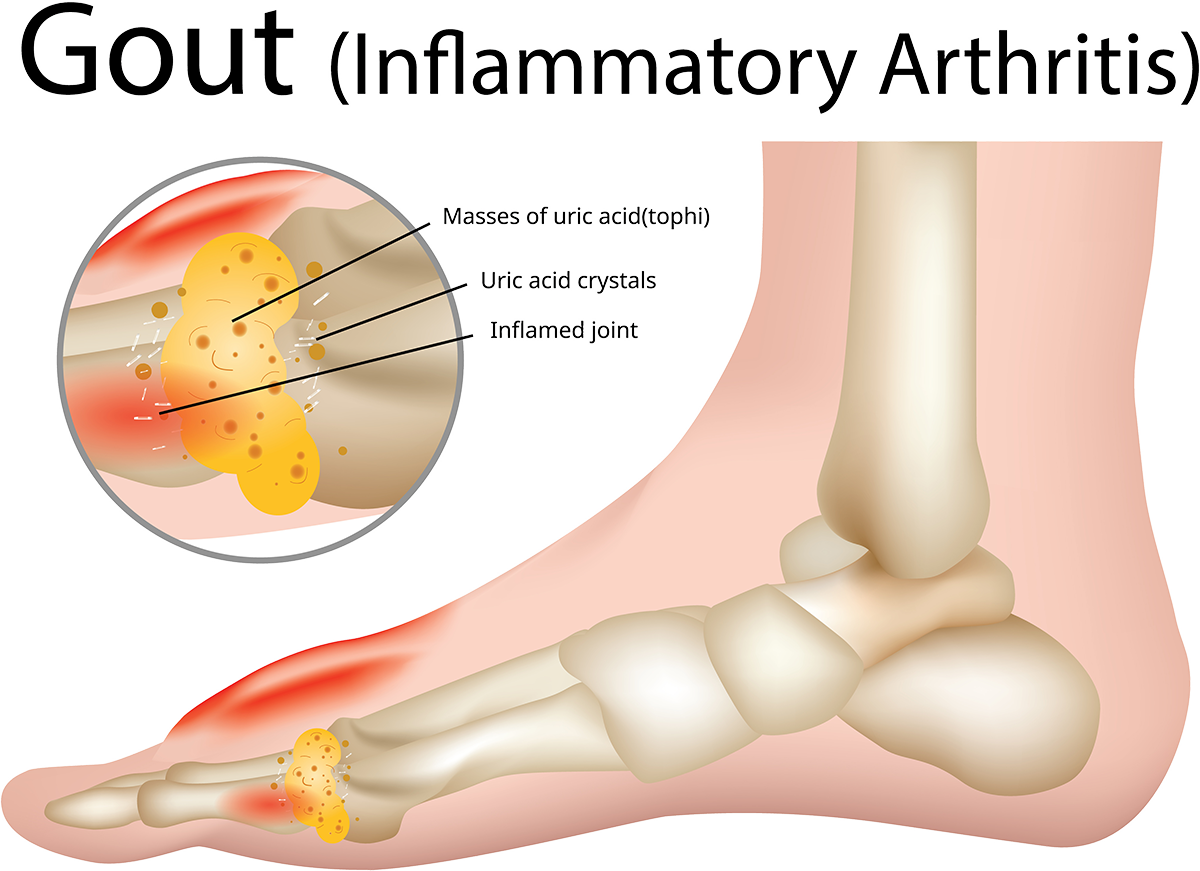

Gout flare symptoms can be improved with non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), but repeated courses of these without urate-lowering therapy can indicate poor care, especially because of the potential for kidney disease and development of tophi (lumpy deposits of uric acid crystals that form around the joint).4 NSAID dispensing without any urate-lowering therapy has consistently decreased over time for Māori and Pacific peoples, while rates for non-Māori, non-Pacific populations have not changed.

However, overall, 41 per cent of Māori and 46 per cent of Pacific peoples with gout were dispensed an NSAID, compared with 35 per cent of non-Māori/non-Pacific peoples diagnosed with gout. Younger people, particularly Māori and Pacific peoples, were dispensed NSAIDs at significantly higher rates.1 Treatment with repeated prescriptions of NSAIDs can be a poor and potentially dangerous stopgap.4

We still have not achieved optimal gout care. Although hospital admissions for gout for the general population have reduced over time, Māori and Pacific peoples are about five and 10 times, respectively, more likely to be hospitalised with a primary diagnosis of gout, relative to non-Māori, non-Pacific people.1

Pathophysiology – it’s not lifestyle

The first strong community belief to dispel is that having gout is the person’s fault because they have been eating the wrong food or drinking a little alcohol. There is a very strong genetic basis for hyperuricaemia (a high level of uric acid in the blood), which is the cause or driver for gout. Māori and Pacific peoples typically have a genetic predisposition for gout, and when discussing the diagnosis, most Māori or Pacific men with gout will say they have relatives with gout.

Belief – “It’s my fault because I eat the wrong stuff.”

It is vital to dispel beliefs about certain foods being the cause of gout and explain that some foods may be a trigger. If someone restricts foods that are culturally important, such as seafood, and still gets gout, they may feel frustrated and guilty, as though it is their fault for not being “good”. Changing diet alone rarely prevents gout flares.

The genetic predisposition to gout is complex, with different polymorphisms, but the end result is that, for some people, high serum urate levels result in precipitation of uric acid crystals in cartilage, tendons, ligaments and, in the longer term, larger joints.

Key points

- Acceptance of the need for long-term treatment with allopurinol is important, so patients do not depend on short-term NSAIDs.

- Allopurinol should be discussed at the first gout flare, and strongly recommended at the second; there is no need for two gout flares annually.

- A primary risk factor for gout is genetics – diet only plays a minor role. Gout and variation in its treatment contributes to inequity.

- Gout occurs earlier and is more severe in Māori and Pacific peoples, so more prescribing of urate-lowering therapy, earlier, is needed to achieve equitable care.

Gout is a chronic inflammatory disease and inadequate treatment to reduce serum urate levels can lead to tophi, chronic gouty arthritis and joint destruction. Tophi indicates poor control of serum urate for more than 10 years.

Urate-lowering treatment (eg, allopurinol) initiated early and used regularly and consistently, rather than lifestyle and dietary changes, will help patients achieve long-term symptom control.

Although the principles for treating and preventing gout appear relatively simple, we are not doing at all well in this country. The answer is not as simple as “we need to prescribe more”, and it is not helpful to hear the rationale for poor control being “patients just don’t take their allopurinol”. We can do better, though it may require a different approach.

Interventions promoting patient education and follow-up appear successful. University of Auckland investigators conducted a systematic review of international studies that looked at 18 interventions to improve urate-lowering treatment uptake in patients with gout.5 These interventions went beyond the usual care provided in primary care and included nurse-led, pharmacist-led and multidisciplinary, multifaceted interventions.

Improvement in serum urate levels was seen for all interventions, but nurse-led interventions appeared most effective. These included investigating beliefs and perceptions about gout and its management, patient education, reminders for urate-level tests and prescription refills, and monitoring until target urate levels were achieved. Patient education encouraged shared decision-making and provided information on the nature of gout, its causes and consequences.

Access is an issue, but it is broader than this, and a holistic model of care is required that involves the community, greater co-design and perhaps social marketing (eg, sporting heroes advocating for taking allopurinol). Māori and Pacific men may benefit from messaging that enhances mana, empowering them to continue taking allopurinol regularly to prevent recurrent gout attacks.

Emphasis is needed on the important role of whānau in encouraging and helping their men to engage with the health system about screening for, or managing, gout. Health-care professionals can actively encourage and answer questions from whānau. Involvement of whānau and health promotion in the community both contribute greatly to improved health literacy.

Panel 1. Risk factors and triggers for gout

Risk factors

Genetics:

- Male

- Ethnicity

- Genetic polymorphisms (eg SLC2A9, ABCG2, GCKR, SLC17A1/A3)

Other:

- Increasing age

- Chronic renal disease

- Metabolic syndrome

- Heart failure

Triggers

Dietary:

- Sugar (fructose)- sweetened drinks

- Shellfish

- Red meat

- Alcohol

Drugs:

- Diuretics

- Cyclosporin, tacrolimus

Other:

- Injury, trauma

Triggers for gout

Genetics and ethnicity are key risk factors for gout, along with increasing age, and male gender (see Panel 1). Dietary triggers for acute gout flares include foods containing high levels of purine, such as shellfish and red meat, and also alcohol.

Recently, fructose has been shown to inhibit renal excretion of urate. Men who daily consumed two or more servings of sugar-sweetened drinks increased their risk of gout by 85 per cent, compared with those who consumed less than one serving monthly. Compare this with the 49 per cent increase in risk from ingesting 15-30g/day of alcohol.6

Minor trauma and emotional or medical stress may also trigger gout. Some people may think they incurred an injury such as a sprained ankle, but it is important to remember that injury can trigger gout.

There is debate about the significance of potential diuretic-induced gout, due to possible confounders.7 Diuretics are not contraindicated in people with gout but would not usually be first-line blood pressure-lowering agents in people with, or at high risk of, gout. Individual benefit–risk implications should be considered.

Low-dose aspirin can cause changes in renal excretion of urate, but this effect is variable and usually small.8 An adjustment of urate-lowering therapy may be required, but discontinuation or avoidance of low-dose aspirin is usually not necessary.

Allopurinol may be less effective in people on furosemide,9 but this is usually overcome by increasing the allopurinol dose.

Diagnosis

The symptoms of gout are usually clear – severe throbbing or burning pain, swelling, redness and a warming of the area affected. Touching or weight-bearing can result in excruciating pain. Flares classically occur in the big toe, but ankles, knees, elbows and fingers may be affected over time. These symptoms, coupled with ethnicity and/or family history, usually provide a good basis for a clinical diagnosis.

Forms of arthritis may mimic gout (eg, septic arthritis, psoriatic arthritis and osteoarthritis among others), so care is required to determine that gout that has “moved to the knee” is not osteoarthritis.

Joint aspiration is usually only performed when there is doubt about the diagnosis. For some people, if there is uncertainty about the diagnosis, a dual-energy CT scan detecting urate in the joints will confirm a diagnosis of gout.

A high serum urate level will help confirm gout, but a lower level does not discount it.

Gout is associated with comorbidities, including metabolic syndrome, which is estimated to be present in 63 per cent of people with gout, compared with 25 per cent of people without gout.10

Also, 40–74 per cent of people with gout will have high blood pressure.11 Approximately one-quarter of people with gout have diabetes, and approximately 70 per cent have a creatinine clearance lower than 90ml/min. People with gout have an increased risk of death from cardiovascular disease.12

The multifaceted nature of gout, and the fact it rarely exists in isolation of comorbidity, are reasons why care for people with gout needs to be holistic rather than fragmented and siloed. A person presenting with gout needs to be screened and have other potential comorbidities managed. There is currently no clear recommendation to treat asymptomatic hyperuricaemia.

Advantages and disadvantages of medicines for acute gout flares

Prednisone

Advantages:

- As effective as naproxen 500mg twice daily.

- Suitable for people with impaired renal function.

Disadvantages:

- Short-term increase in blood glucose for people with diabetes.

- Potential for short-term fluid retention and increased appetite.

Dosage:

- 0.5mg/kg for 5-10 days.

- 40mg every morning for 5 days, then 20mg daily for 5 days is usually considered the “standard” dosage.

NSAIDs

Advantages:

- Effective.

Disadvantages:

- Adverse effects such as gastrointestinal bleeding, renal impairment and increased cardiovascular risk.

- Avoid in renal impairment (eGFR <60ml/min/1.73m2); use a lower dose if eGFR 45-60ml/min/1.73m2.

- Avoid in people with heart failure or high cardiovascular risk, and 12-24 months after myocardial infarction.

- There is a tendency for patients to exceed the prescribed dosages due to severe gout pain.

Dosage:

- Use at full dosage (eg, naproxen 500mg twice daily).

- In people with creatinine clearance <60ml/min, reduce dose and use with caution due to risk of renal failure, especially in Māori and Pacific peoples.

- Minimise use to ≤5 days if possible.

- Only prescribe or dispense small amounts (eg ≤20 tablets) – diclofenac tablets are frequently shared, hence there is risk of adverse effects in vulnerable people.

colchicine

Advantages:

- Specific for gout.

- Effective when started early.

Disadvantages:

- Preferable to start within 12-24 hours.

- Toxic in overdose, which occurs with a small number of tablets.

- Dose reduction in renal impairment.

- Potential interactions with cytochrome P450 3A4 inhibitors (diltiazem, macrolides, itraconazole, cyclosporin) and take care with statins.

- Do not use in pregnancy.

Dosage:

- 1mg stat followed by 0.5mg every 6 hours; maximum of 2.5mg on the first day, 1.5 mg on subsequent days (dosing reduced to 3 times daily), no more than 6mg in 4 days.

- Low-dose alternative: 1mg stat, followed by 0.5mg 1 hour later; a further 0.5mg may be taken once or twice daily for 2-3 days more.

- Dosage is reduced for people ≤50kg, or with a creatinine clearance ≤50ml/min; maximum dosage is 1mg in 24 hours, and no more than 3mg over 4 days.

- Once the maximum cumulative dose is reached, colchicine should not be used again for at least 3 days.

Acute treatments

Belief – “I just need something to get rid of the pain when I have an attack, and then it’s all okay.”

The choice of acute medicines therapy – prednisone, NSAIDs or colchicine – is influenced by comorbidities as there is little difference in effectiveness between the medicines (see table above).13, 14

The maximal dosage and hazards of excessive colchicine need to be stressed to avoid the acute toxicity likely to result from a “more is better” perception. In Auckland, a case series found eight people died of a colchicine overdose over 15 years, with doses between 18mg and 24mg.15

Belief – “The Voltaren tablets don’t hurt me – they get rid of the pain.”

A 2020 New Zealand study found that, after adjusting for other risk factors, Māori and Pacific peoples were significantly more likely than European patients to be hospitalised with serious complications – upper gastrointestinal bleed, heart failure – after being dispensed NSAIDs.16 Furthermore, the risk of acute kidney injury for Māori was significantly higher compared with Europeans. This highlights the need to be especially wary of prescribing NSAIDs in Māori and Pacific peoples who have a lower estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) than would be expected for their age.

Preventive medicines

Preventive medicines include allopurinol, febuxostat and probenecid, and two biologics not readily available in New Zealand, rasburicase and pegloticase. Allopurinol remains the first-line preventive urate-lowering medicine in New Zealand and internationally.

Belief – “You need two gout flares a year before you consider allopurinol.”

In our high-risk population of Māori and Pacific peoples, preventive urate-lowering therapy should be discussed when someone presents with their first gout flare, and strongly recommended after the second flare. Studies have found urate-lowering therapy, although indicated, is often delayed, sometimes for a period of several years.17 For most, and especially Māori and Pacific people with a family history, gout is not going to go away, and every flare will be causing joint damage. Māori and Pacific people also require a full assessment for comorbidities.

The resistance to taking a lifelong tablet is understandable. Patients often stop and restart allopurinol. Patience is required, especially as the process requires slow titration with each restart if the patient stops allopurinol for more than one month. If stopped for less than one month, the previous dose can be restarted.

Understanding factors that result in stopping preventive therapy is important. These include:

- difficulty developing a medicines-taking habit

- beliefs and attitudes about medicines

- misunderstanding of the need for lifelong therapy

- wanting to “test” if allopurinol is still needed

- confusing preventive therapy with acute therapy.

Studies indicate that people take allopurinol only about 62 per cent of the time.18 Younger people and those not taking other regular medicines are less likely to take their allopurinol.

This emphasises that it is not necessarily the prescribing of allopurinol that is the issue. It is imperative that ongoing, consistent advice and education is given, addressing the individual’s concerns. Ensure medicine and lifestyle conversations/interventions happen at distinct times in the patient/whānau journey: at initiation, flare occurrences, and when working towards stabilisation on long-term treatment.

It is also important to develop a relationship with the person – determine their beliefs, values and understanding, and the factors that may reduce the likelihood of taking allopurinol continuously. The Ask Build Check tool may also be helpful. This model comprises three steps: ask what the person knows, thinks, believes or does; build new information on to what is already known, and check how clearly and effectively you have communicated.

Allopurinol

Initiation

Traditionally, allopurinol has been started once an acute flare has resolved. This required the person to remember not only to start the allopurinol but also the instructions for titration. This requirement plus the need to take prophylactic medicine, such as a low-dose NSAID or colchicine, for at least three months could be seen as confusing and inconvenient.

Belief – “You can’t start allopurinol during an acute gout flare.”

However, there is scant evidence that initiation of urate-lowering therapy should be delayed until a flare is no longer painful. Rather, studies have found initiating a urate-lowering treatment during a flare has no significant impact on the duration of the flare or its severity.19

Initiating allopurinol along with prophylactic medicine increases complexity, but using blister packaging is helpful for managing acute treatment, titration of allopurinol and short-term use of prophylactic medicine. The importance of education and advice, even with blister packaging, cannot be underestimated. For starter pack regimens, see two PDFs: For health professionals – Treating and preventing gout in 7 minutes at Gout Prevention – Goodfellow Unit.

It is imperative patients accept the need for long-term treatment with allopurinol and not depend on short-term NSAIDs. Accepting this takes time and can be challenging for all. Multiple health professionals and community care workers can support interventions that involve patient engagement. These must empower patients to share decisions about their care and make the sustained behavioural changes required.

Dosing

Gout flare reduction is on a continuum of serum urate levels, but the target that provides a good balance between gout flares and pill burden is <0.36mmol/L (<0.30mmol/L if the patient has tophi). Ideally, the main clinical outcome of urate-lowering therapy is no gout flares, although if gout does occur, it is less frequent and less severe.

Renal function is used to establish the starting dose of allopurinol: patients with reduced renal function initially start on lower doses.

Traditionally, the dosage of allopurinol was considered to be 300mg daily. However, in New Zealand, to achieve a target serum urate level of less than 0.36mmol/L, a mean dosage of 360mg daily, or median dosage of 450mg daily, is required.

Prophylactic cover

If someone starts allopurinol and a gout flare is precipitated, it is difficult to convince them to restart allopurinol as, in their mind, it becomes associated with causing gout. Therefore, prophylactic cover is needed when initiating allopurinol (eg colchicine, NSAID). This is an off-label (unlicensed) use of colchicine, but for people in whom NSAIDs should be used cautiously, it is effective cover. One colchicine tablet daily is preferred, and two tablets daily should not be exceeded.

Prophylactic cover needs to be continued for at least six months, or for three months after achieving target serum urate levels.

Adverse effects

Allopurinol is usually well tolerated. Allopurinol hypersensitivity syndrome (AHS) is the most concerning adverse effect, due to a mortality of about 25 per cent. AHS is a delayed hypersensitivity reaction, estimated to occur in 0.1 per cent of people, usually within 30 days.20 It presents as a toxic epidermal necrolysis or Stevens–Johnson syndrome-type rash, with fever, eosinophilia, leucocytosis and possibly hepatic and renal dysfunction. Anyone with a rash should seek immediate advice.

Belief – “Allopurinol dose is limited by renal function.”

Starting at a high dose, or titrating too quickly, can increase the risk of both gout flares and AHS.17, 20 The final dose of allopurinol is now the dose that achieves a serum urate level of less than 0.36mmol/L, rather than a maximum dose according to renal function. Once the optimal allopurinol dose is obtained, there is no need to reduce the dose if renal function declines.

The potential for drug–drug interactions should always be checked before starting gout medications. Azathioprine, mercaptopurine, ACE inhibitors, warfarin, diuretics and penicillins are among drugs potentially interacting with allopurinol.21

Other urate-lowering medicines

Febuxostat is similar to allopurinol in its mechanism of action. Avoid for patients with pre-existing major cardiovascular diseases.22

Losartan is not a specific urate- lowering agent but may reduce serum urate levels slightly. If an ACE inhibitor or angiotensin II receptor blocker is being considered for a patient with gout, then losartan may be preferable. Similarly, atorvastatin and empagliflozin may be helpful adjuncts. Other preventive therapies are available through specialist consultation.

Panel 2: What to consider for practice

Keep in front of mind:

- Try to improve access to regular dispensing of preventive gout medicine (persistence and adherence).

- Help people to accept and stick with allopurinol.

- Look for inappropriate use of NSAIDs.

- Earlier detection and initiation of preventive treatment is important, particularly for Māori and Pacific peoples.

- Women are also affected by gout.

- Gout may present as a traumatic injury.

Provide consistent advice:

- Gout is caused by genetics. Dispel beliefs about food and alcohol being a major cause. Food is just a trigger.

- Once on allopurinol and at serum urate level target, small amounts of trigger foods may be eaten.

- Even if gout is controlled, do not drink sugar-sweetened drinks, fizzy drinks or high-fructose drinks.

- Do not take more than the maximum doses of tablets prescribed, even where there is a gout flare.

- Explain about the risks of excessive doses of NSAIDs and colchicine.

- Do not give or lend medicines for gout to anyone.

- Allopurinol titration takes three to six months, and extra medicine is needed initially.

- Confirm what the target serum urate level is and how this is monitored.

- Explain that flares may still occur in the first year of treatment, but these reduce over time and are less severe.

- Advise not to stop allopurinol, even during an acute flare.

- Explain that treatment with a preventive therapy is lifelong – stopping the medicine will cause the serum urate level to increase again.

- Describe allopurinol hypersensitivity syndrome symptoms, especially the rash, and the importance of stopping the allopurinol and seeing a doctor immediately.

- Provide written information plus website links for further information:

Free support and advice are available to people who want to talk about their gout. Call 0800-663-463 or fill out an online form to request a call back at Arthritis New Zealand.

How can we do better?

Gout is a health condition for which inequity pervades. Māori and Pacific peoples are much more likely to get gout, and earlier detection and initiation of preventive treatment is needed. Māori and Pacific peoples are also less likely to be able to access care, to be prescribed appropriate medicines, to be followed up and to be provided with understandable education.4, 16

Initial explanation about gout and the long-term nature of complications and treatments is important, plus the emphasis that allopurinol treatment is lifelong. Practices with health improvement practitioners and health coaches may find these people can get patients engaged and provide good understandable information.

Work by Leanne Te Karu (Muaūpoko/Whanganui), from the University of Auckland, and colleagues has identified systemic barriers. A multifaceted, multidisciplinary and culturally-driven model of care is being investigated to improve the delivery of care for gout.

Health-care providers need to be proactive and talk about gout and its impact on work, recreation and relationships. All members of the team can contribute, including GPs, pharmacists, nurses, physiotherapists, podiatrists and kaiāwhina. We all need to give consistent advice (see Panel 2) and recognise barriers to access – often not a lack of prescribing but the ongoing, patient and whānau-centred encouragement and reinforcement that is required.

Linda Bryant, MClinPharm, PhD, PGCert(prescr) is a prescribing pharmacist working in the Newtown Union Health Service, Wellington, and Porirua Union and Community Health Service general practices. Her focus is on inequity, particularly in long-term conditions such as cardiovascular disease, diabetes, respiratory diseases and gout.

References

- Health Quality & Safety Commission New Zealand. (2021). Atlas of Healthcare Variation: Gout.

- Dalbeth, N., House, M. E., Horne, A., Te Karu, L., Petrie, K. J., McQueen, F. M., & Taylor, W. J. (2013). The experience and impact of gout in Māori and Pacific people: a prospective observational study. Clinical Rheumatology, 32(2), 247–51.

- Ministry of Health. (2020). Pharmaceutical data web tool version 03. (Data extracted from Pharmaceutical Collection on March 5, 2020.)

- Dalbeth, N., Dowell, T., Gerard, C., Gow, P., Jackson, G., Shuker, C., & Te Karu, L. (2018). Gout in Aotearoa New Zealand: the equity crisis continues in plain sight. New Zealand Medical Journal, 131(1485), 8-12.

- Gill, I., Dalbeth, N., ‘Ofanoa, M., & Goodyear-Smith, F. (2020). Interventions to improve uptake of urate-lowering therapy in patients with gout: A systematic review. BJGP Open, 4(3), bjgpopen20X101051.

- Choi, H. K., & Curhan, G. (2008). Soft drinks, fructose consumption, and the risk of gout in men: prospective cohort study. BMJ, 336(7639), 309-12.

- Hueskes, B., Roovers, E., Mantel-Teeuwisse, A., Janssens, H., van de Lisdonk, E., & Janssen, M. (2012). Use of diuretics and the risk of gouty arthritis: a systematic review. Seminars in Arthritis & Rheumatism, 41(6), 879-89.

- Zhang, Y., Neogi, T., Chen, C., Chaisson, C., Hunter, D., & Choi, H. (2014). Low-dose aspirin use and recurrent gout attacks. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases, 73(2), 385-90.

- Stamp, L. K., Barclay, M. L., O’Donnell, J. L., Zhang, M., Drake, J., Frampton, C., & Chapman, P. (2012). Furosemide increases plasma oxypurinol without lowering serum urate – a complex drug interaction: implications for clinical practice. Rheumatology (Oxford), 51(9), 1670-76.

- Choi, H. K., Ford, E. S., Li, C., & Curhan, G. (2007). Prevalence of the metabolic syndrome in patients with gout: the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Arthritis & Rheumatology, 57(1), 109-15.

- Stamp, L. K., & Chapman, P. T. (2013). Gout and its comorbidities: implications for therapy. Rheumatology (Oxford), 52(1), 34-44.

- Choi, H. K., & Curhan, G. (2007). Independent impact of gout on mortality and risk for coronary heart disease. Circulation, 116(8), 894-900.

- Liu, X., Sun, D., Ma, X., Li, C., Ying, J., & Yan, Y. (2017). Benefit-risk of corticosteroids in acute gout patients: An updated meta-analysis and economic evaluation. Steroids, 128, 89-94.

- Roddy, E., Clarkson, K., Blagojevic-Bucknall, M., Mehta, R., Oppong, Avery, A., Hay, E., Heneghan, C., Hartshorne, L., Hooper, J., Hughes, G., Jowett, S., Lewis, M., Little, P., McCartney, K., Mahtani, K., Nunan, D., Santer, M., Williams, S., & Mallen, C. (2020). Open-label randomised pragmatic trial (CONTACT) comparing naproxen and low-dose colchicine for the treatment of gout flares in primary care. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases, 79(2), 276-84.

- Jayaprakash, V., Ansell, G., & Galler, D. (2007). Colchicine overdose: the devil is in the detail. New Zealand Medical Journal, 120, U2402.

- Tomlin, A., Woods, D. J., Lambie, A., Eskildsen, L., Ng, J., & Tilyard, M. (2020). Ethnic inequality in non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug-associated harm in New Zealand: A national population-based cohort study. Pharmacoepidemiology & Drug Safety, 29(8), 881-89.

- BPACnz. (2021). Managing gout in primary care (PDF, 1.53 MB).

- Harrold, L. R., Andrade, S. E., Briesacher, B. A., Raebel, M., Fouayzi, H., Yood, R., & Ockene, I. (2009). Adherence with urate-lowering therapies for the treatment of gout. Arthritis Research & Therapy, 11(2), R46.

- FitzGerald, J., Dalbeth, N., Mikuls, T., Brignardello-Petersen, R., Guyatt, G., Abeles, A., Gelber, A., Harrold, L., Khanna, D., King, C., Levy, G., Libbey, C., Mount, D., Pillinger, M., Rosenthal, A., Singh, J., Sims, J., Smith, B., Wenger, N., Bae, S., Danve, A., Khanna, P., Kim, S., Lenert, A., Poon, S., Qasim, A., Sehra, S., Sharma, T., Toprover, M., Turgunbaev, M., Zeng, L., Zhang, M., Turner, A., & Neogi, T. (2020). 2020 American College of Rheumatology guideline for the management of gout. Arthritis Care & Research (Hoboken), 72(6), 744-60.

- Stamp, L., Taylor, W., Jones, P., Dockerty, J., Drake, J., Frampton, C., & Dalbeth, N. (2012). Starting dose is a risk factor for allopurinol hypersensitivity syndrome: a proposed safe starting dose of allopurinol. Arthritis & Rheumatology, 64(8), 2529-36.

- New Zealand Formulary. (2021). Allopurinol.

- A. Menarini New Zealand Pty Ltd. (2021). New Zealand Datasheet: Adenuric 80 mg, 120 mg film coated tablets (PDF, 208 KB).

This article has been endorsed by the College of Nurses Aotearoa for 60 minutes professional development (CNA084). Test your learning after reading this by completing the assessment.

This article has been endorsed by the College of Nurses Aotearoa for 60 minutes professional development (CNA084). Test your learning after reading this by completing the assessment.