Last month the Minister of Health Simeon Brown announced a bonding scheme in which more than 900 newly-qualified health professionals were set to receive financial support to kick-start their careers in health, particularly primary health care.

But the chair of NZNO’s college of primary health care nurses Tracey Morgan said the Government’s announcement it would halt all pay equity claims threatened any benefits of the scheme.

“These bonding scheme numbers are like putting a band-aid on a gunshot wound – the bleeding will just not stop, especially in light of [the pay equity] news,” Morgan said.

Brown said the voluntary bonding scheme provided financial incentives to encourage new graduates to stay and work in the country – particularly in hard-to-staff regions and specialties where they were needed most.

“We want more of our nurses, midwives, anaesthetic technicians, and other critical health professions to stay in New Zealand after they graduate,” Brown said.

“We know there is further work needed to improve access to primary care and boost the primary care workforce, which will be the focus of the intake for 2025.”

However, Morgan said while the scheme would see 649 new nurses and midwives stay grounded in the country for the next three to five years, the pay equity halt could force more than 3500 experienced nurses in primary health care to consider whether they look for jobs in other sectors. Some may also head overseas to work as nurses while others stay and “continue to bleed”.

‘This morning a woman who has been a nurse for more than 40 years, told me she quit her job after seeing the news last night. She’s sick of fighting for fairer pay.’

“There’s likely to be many nurses like her who sadly will leave over the next three to five years. And the numbers could be more than what the Government is bringing in the door via their scheme — so two walking out the back door, one walking in the front door is a very real risk right now.”

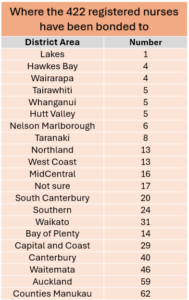

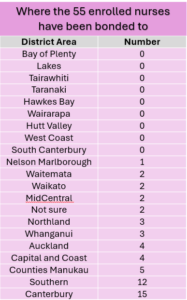

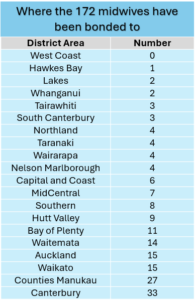

The bonding scheme kickstart for new graduates (172 midwives, 422 registered nurses and 55 enrolled nurses) was simply not enough, Patient Voice spokesperson Malcolm Mullholand said.

“Having just toured the country including rural New Zealand, patients, nurses, doctors and health-care workers are crying out for more health professionals — and that was before their careless pay equity decision,” he said.

“These new bonding scheme numbers most probably will not have any real impact on the ground as nurses and doctors already working in those districts have told me they need thousands more health professionals right now — 900 just will not cut it.”

There did not appear to be any relief in the latest bonding numbers for rural and Māori communities, Mullholand said.

‘It’s insulting to see that almost half the districts in this country got no enrolled nurses in this scheme, including Tairāwhiti and West Coast.’

“Tairāwhiti has the highest Māori population in the country and serious health inequities. Then there’s the West Coast, one of the country’s most rural areas, whose hospital in Buller has no after-hours emergency service anymore.”

A Bay of Plenty nurse who recently moved overseas to Queensland told Kaitiaki that the bonding scheme did not work for her.

“You have to bleed for three years to get the first financial incentive then bleed again for another two years to get the next drop,” the hospital nurse, who wants to remain anonymous, said.

“I gave up, didn’t stick around for the three years because the bleeding just got too much. I said ka kite to Aotearoa and chose a nursing job in Australia that pays me a lot more, even if I add in the bits and pieces from this scheme.

“It wasn’t just the money that made me leave my homeland. The chronic shortage in the health workforce had led to burn-out and a toxic environment that spread through the hospital I was working at,” the expatriate nurse said.