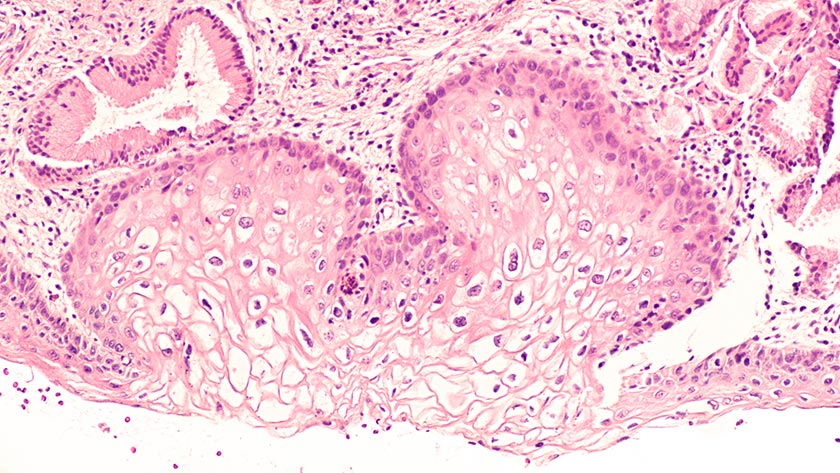

Instead of being tested for abnormal cervical cells, people will be offered a test for human papillomavirus (HPV) which causes almost all cervical cancer. HPV testing is more sensitive in detecting pre-cancer than cytology, so tests will only be needed every five years instead of the current three.

This change also brings options: A self-test in the privacy of a clinic bathroom or at home, or a clinician-taken test where the experience of cervical screening is the same as it is now, with laboratory testing for HPV.

The World Health Organization has called for the elimination of cervical cancer through vaccination and screening for HPV (including self-testing) and treatment.1

International and local research suggests that HPV self-testing is more acceptable and likely to improve equitable access compared to current screening.

So why has it taken so long to have HPV testing available here?

In 2016, then-Minister of Health Jonathan Coleman announced that Aotearoa would move to an HPV primary screening programme within two years.2

At the time, international data suggested self and clinician tests were similarly effective in detecting pre-cancerous cells, if a PCR (polymerase chain reaction) test was used.3 A subsequent study into the views of wāhine Māori was overwhelmingly positive.4

Local studies began in Auckland and Northland to determine how acceptable self-testing was to people – and whether it might encourage those who weren’t participating in cervical smears. These studies showed that HPV self-testing was highly acceptable and empowering.

Further, the Auckland study showed a mail-out test drew higher participation for Māori than a clinic-based test. Together, the studies suggested that – with the right design – self-testing was likely to increase overall participation in cervical screening.5

In 2018, an updated meta-analysis confirmed self-testing was equivalent to a clinician-taken HPV test to detect pre-cancer if a PCR laboratory test was used.6 Studies in Aotearoa were well under way by this time with universally positive feedback on self-testing, particularly powerful from those who had detected HPV through self-testing and gone onto have treatment.

“Thank you so much I really appreciated being able to self-test. It had actually been nearly 30 years since I had a smear test because of embarrassment and bad experiences…7

“…when I got home to my son I really felt how lucky I am, lucky that my GP and nurse picked me for this study and lucky that I don’t have cancer, a couple more years and it would have been too late. You know I would not have had a smear. Dr [X] would ask me to have one every time I came in, but I didn’t mind getting on the table when I knew I had HPV.”7

However, the existing NCSP register needs to be upgraded or replaced to track HPV test results, as required by law. Funding for this was finally achieved in May 2021, when it was also announced that self-testing would become an option in 2023.8

Many have influenced this change. Researchers, Māori health advocates, colposcopists, cervical screening nurses, sexual health doctors, public health physicians, community advocates and whānau have kept the mission in front of Government. Momentum grew with hui in 2019 and 2020. We have approached ministers and shared petitions, evidence and feedback from participants and health professionals. Trailblazers from the Cartwright Inquiry, Smear Your Mea and women’s health groups have all contributed to making HPV testing a priority.

Aotearoa now has an opportunity to design a screening programme focused on equity, partnership and autonomy for women.

For many nurses who are cervical sample takers, the option of self-testing will mean changes to the screening procedure and how it is communicated – particularly ensuring those needing further investigation are followed up.

For nurses who both vaccinate and screen, conversations about HPV are more important than ever. A campaign on the importance of having vaccination and screening for HPV together, rather than separately, will support health literacy.

We can start working towards a successful transition now by ensuring people have access to evidence-based information.

Let’s collectively contribute to the elimination of cervical cancer in Aotearoa now and in the future through positive, empowering, evidence-based messaging for our patients, whānau and ourselves.

See also: Nurses celebrate, lament long fight.

Key messages for health professionals

- HPV testing has a very high negative predictive value (so can have a longer screening interval) and is a more sensitive test than cytology.9

- A self-test for HPV is equivalent to a test taken by a clinician with a speculum (as long as a PCR test is used at the laboratory).

- Finding and sampling the cervix is not required for self-testing – viral DNA is found all over the lower genital tract.

- People who have symptoms including pelvic pain, unusual bleeding or discharge should be encouraged to have a speculum examination.

- If HPV is detected on a self-taken sample, a smear test or colposcopy is required to determine whether cell changes have occurred.

- The current screening programme continues to be safe and effective. It is important that people keep having their regular cervical screening tests and not wait for the change to HPV primary screening in 2023.

HPV self-test fact box

- In 2023, a five-yearly human papillomavirus (HPV) test will replace the current three-yearly smear test for 1.4 million eligible women aged 25-69. Swabbing the genital tract for HPV virus can be done by a patient or clinician using a tool similar to a cotton bud. Results are 99.8 per cent accurate compared to a current accuracy rate of about 90 per cent.

- Cervical cancer is almost entirely preventable through vaccination screening – yet every year 160 women develop it and 50 die from it in New Zealand.

- Clinical modelling predicts the move to HPV screening will prevent about 400 additional cervical cancers over 17 years and save around 138 lives. A third of the cases prevented and lives saved will be wāhine Māori. Wāhine Māori die from cervical cancer at more than twice the rate of non-Māori.

- Only 61 per cent of eligible Māori access New Zealand’s National Cervical Screening Programme, which has reduced cervical cancer rates and death rates by more than half since 1990.

- HPV primary screening provides 60 to 70 per cent more protection against invasive cervical cancer when compared with cytology (cervical smear) screening.

– Sourced from Waitemata DHB cervical screening clinical nurse specialist Jane Grant and Associate Health Minister Ayesha Verrall.

Jane Grant, RN, BHSc Nursing, is a clinical nurse specialist working for Auckland and Waitematā DHBs. She is also a cervical screening coordinator and involved in HPV self-testing research.

References

- World Health Organization. (2020). WHO recommendations on self-care interventions: human papillomavirus (HPV) self-sampling as part of cervical cancer screening.

- National Screening Unit. (2016). Planned changes to cervical screening test in 2018.

- Arbyn, M., Verdoodt, F., Snijders, P. J., Verhoef, V. M., Suonio, E., Dillner, L., Minozzi, S., Bellisario, C., Banzi, R., Zhao, F. H., Hillemanns, P., & Anttila, A. (2014). Accuracy of human papillomavirus testing on self-collected versus clinician-collected samples: a meta-analysis. The Lancet. Oncology, 15(2), 172–183. doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(13)70570-9

- Adcock, A., Cram, F., Lawton, B., Geller, S., Hibma, M., Sykes, P., MacDonald, E. J., Dallas-Katoa, W., Rendle, B., Cornell, T., Mataki, T., Rangiwhetu, T., Gifkins, N., & Hart, S. (2019). Acceptability of self-taken vaginal HPV sample for cervical screening among an under-screened Indigenous population. The Australian and New Zealand Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, 59(2), 301–307. doi.org/10.1111/ajo.12933

- Brewer, N., Bartholomew, K., Grant, J., Maxwell, A., McPherson, G., Wihongi, H., Bromhead, C., Scott, N., Crengle, S., Foliaki, S., & Cunningham, C. (2021, April 15). Acceptability of human papillomavirus (HPV) self-sampling among never-and under-screened Indigenous and other minority women: a randomised three-arm community trial in Aotearoa New Zealand. medRxiv.

- Arbyn, M., Smith, S. B., Temin, S., Sultana, F., & Castle, P. (2018). Detecting cervical precancer and reaching underscreened women by using HPV testing on self samples: updated meta-analyses. British Medical Journal, 363, k4823. doi:10.1136/bmj.k4823

- Sherman, S., Bartholomew, K., Brewer, N., Bromhead, C., Crengle, S., et al. Human Papillomavirus (HPV) self-testing among un- and under-screened Māori, Pacific and Asian women: a preference survey and interviews with clinical trial non-responders (in preparation).

- Little, A., & Verrall, A. (2021, May 9). Budget delivers improved cervical and breast cancer screening. Beehive.

- Ronco, G., Dillner, J., Elfström, K., Tunesi, S., Snijders, P., Arbyn, M., Kitchener, H., Segnan, N., Gilham, C., Giorgi-Rossi, P., Berkhof, J., Peto, J., Meijer, C., & International HPV screening working group. (2014). Efficacy of HPV-based screening for prevention of invasive cervical cancer: Follow-up of four European randomised controlled trials. The Lancet, 383(9916), 524-32.