In New Zealand, people with disabilities are assured access to health, education, accommodation and employment. For nurses, this means employment free from discrimination or stigmatising attitudes. Perceived discrimination of any sort is not only unkind and unfair, but it can also prevent people from accessing the help they need to carry out their roles.

This article identifies some of the guidance available to nurses for working alongside people with disabilities, and the supports nurses who have a disability or impairment develop for themselves to manage their nursing responsibilities.

The terms disability and impairment are often used interchangeably in descriptive and research literature. According to the New Zealand Disability Strategy 2016-2026,1 disability is defined as:

Something that happens when people with impairments face barriers in society that limits their movements, senses or activities. (p49)

Conversely, an impairment is:

A problem with the functioning of, or structure of somebody’s body. (p49)

Definitions

The definitions used in the disability strategy are consistent with the social model of disability, where disability stems from societal, environmental and social attitudes causing barriers which dis-able the person. This differs to the medical model of disability in which disability implies a deficit that reduces the person’s quality of life and needs to be fixed or treated.1, 2, 3, 4

The disability strategy urges society, the community and government agencies to incorporate inclusion of people living with a disability and move towards a non-disabling society. The strategy, intended to guide policy development and practices nationally, explains the role and responsibilities required of society and the community so people with disabilities are not discriminated against or excluded from opportunities that other non-disabled people have access to in employment, health and recreation.1

The Human Rights Act (1993) goes further. This act states it is unlawful to discriminate against people living with a disability.5 This requirement is reflected in the New Zealand Nurses Organisation Code of Ethics for nursing which mentions that “Good collegial relationships are free of discrimination or harassment”.6

While the Nursing Council’s Code of Conduct for nurses does not specifically include working with colleagues with disabilities, it does acknowledge that:

“Your behaviour towards colleagues should always be respectful and not include dismissiveness, indifference, bullying, verbal abuse, harassment or discrimination. Do not discuss colleagues in public places or on social media.”7

In addition to this generic advice, the Nursing Council’s Guidelines for Cultural Safety, the Treaty of Waitangi and Maori Health in Nursing Education and Practice acknowledge (in the categories of difference, principle 1.2) that consumers/clients should not be discriminated against because of age, gender, sexual orientation, ethnicity, race or disability. However, relationships with nursing colleagues who live with a disability are not acknowledged in this guideline.8 Furthermore, the Nursing Council’s Guidelines: Professional Behaviours do not discuss nurse colleague relationships at all.9

The Health Worker Rights fact sheet, based on The Employment Relations Act 2000, stipulates that all health workers should be free from discrimination on the grounds of race, sexual orientation, age, gender, beliefs and disability.10 In addition, the fact sheet states that employment relations must be based on dignity and good faith, which includes not taking any action that would deceive or mislead another party. These statements are generally aimed at employer/employee relationships.

Many of the nurse participants described their reluctance to disclose their disability or impairment or their support needs, for fear of being treated differently or discriminated against.

In a qualitative descriptive research study in 2019/2020, we gathered the experiences and perceptions of 10 registered nurses (RNs) who work with a disability, as defined by the nurse. Many of the nurse participants described their reluctance to disclose their disability or impairment or their support needs, for fear of being treated differently or discriminated against.

Nurses’ experiences

Some of the nurses in the study described the lengths they went to, to be very safe practitioners. Over time, the nurses had each developed a skill that included being “doubly” safe. However, this level of safety often took extra time, and some of their colleagues were not as patient as others.

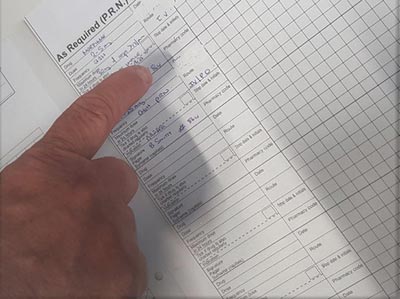

“Terry” went beyond the second checker requirements during medication administration. She asked that her nursing colleagues understand that it may take her longer “to process things”. Compounding that, as a new graduate she also needed time to develop her emerging nursing practice. She asked for tolerance, patience, an understanding of her need to be very safe, and a manager who could separate the “disability” from the new-graduate role.

“Emma” asked that her nursing colleagues not try to separate her from the skills she had developed to be doubly safe when writing up progress notes and correctly describing the wound-care products she had used that day. She asked for her nurse colleagues to encourage her, not discourage her. And she also felt that being able work with colleagues “who don’t make a big deal” about her challenges and being able to have a “bit of a laugh” with colleagues were important to her.

“Tammy” was adamant that she did not “want to give substandard care”. She felt she was very safe and because patient safety was so important to her, being a safe nurse was something she thought about and reflected on all the time. She asked that her colleagues “talk to me, don’t talk about me to others” and: “Please don’t look down on me as I take up non-nursing roles”.

“Cindy” believed that living with a disability made her more aware of safety issues. She felt it was vital to be “confident if you want to double-double check for safety.” She had found that being reflective and being able to “work on yourself and your own attitudes towards others with disabilities” were useful skills and attitudes.

“Pat” had made a mistake early on in her career. This had shaped her belief that “double-checking is important”, so things aren’t missed. She preferred a practical approach to problem-solving conditions for nurses with disabilities such as organising the work “space” to suit their needs, being unafraid to ask, and being upfront about their disability or impairment.

New Zealand nurses, their colleagues and their managers have a national health strategy document, a law and professional guidelines stipulating how they should treat patients and/or colleagues living with disabilities. Despite this, some nurses told us they were reluctant to disclose their disability or impairment in the workplace.

There were a number of reasons for this, including past unpleasant experiences and a perception that they may not get the position they applied for if they were open about their condition. Some also believed that revealing their condition was not necessary as they could manage their disability or impairment by very safe practices and “double, double, triple-checking”.

Nurses in this qualitative study worked hard to ensure they delivered safe nursing care – often going beyond usual practices to be doubly safe.

Margaret E Hughes, RN, BN, PhD, CertAdultTchg, MBS, and Gayle M Rose, RN, BN, MN, GradCert Perioperative, are senior academic staff members in the Department of Health Practice, Manawa, Ara Institute of Canterbury, Christchurch. Henrietta Trip, RN, BN, PhD, DipNS, CertAdultTchg, MHealthSc is a senior lecturer in the Centre for Postgraduate Nursing Studies, University of Otago, Christchurch.

References

- Ministry of Social Development, Office for Disability Issues. (2016). New Zealand Disability Strategy 2016-2026 (PDF, 583 KB).

- Shakespeare, T., & Watson, N. (2001). The social model of disability: An outdated ideology? In Barnartt, S. N. and Altman, B. M. (Eds.), Exploring Theories and Expanding Methodologies: Where we are and where we need to go (Research in Social Science and Disability, Vol. 2), Emerald Group Publishing Limited, Bingley, pp. 9-28. doi.org/10.1016/S1479-3547(01)80018-X

- Hubbard. S. (2004). Disability Studies and Health Care Curriculum: The Great Divide. Journal of Applied Health, 33(3), 184-188.

- Walker, E. R., & Shaw, S. C. K. (2018). Specific learning difficulties in healthcare education: The meaning in the nomenclature. Nursing Education in Practice, 32, 97-98.

- Human Rights Act 1993.

- New Zealand Nurses Organisation. (2009). Code of Ethics (PDF, 809 KB).

- Nursing Council of New Zealand. (2012). Code of Conduct.

- Nursing Council New Zealand. (2011). Guidelines for Cultural Safety, the Treaty of Waitangi and Maori Health in nursing, education and practice (PDF, 609 KB).

- Nursing Council of New Zealand. (2012). Guidelines: Professional Boundaries (PDF, 124 KB).

- New Zealand Nurses Organisation. (2014). NZNO Employment factsheet: Health Workers’ Rights.

This article was reviewed by Dina Whatnell, RN, MN, NP, a nurse practitioner in the mental health and addictions service at Palmerston North Hospital. She specialises in disabilities.