Macabre memories of exhuming villagers murdered during the former East Timor’s struggle for independence 25 years ago intrude every so often on Canterbury military veteran Rachael Collins’ life.

“I have sad memories of exhuming bodies from a cemetery in [the town of] Lolotoe,” said Collins of the gruesome work. As an army medic (who deployed as Rachael Gill), she had accompanied Kiwi soldiers doing the digging in 2000.

“The families were present and they were wailing and crying and calling out in grief,” she said.

Collins, who served as a Royal New Zealand Army Medical Corps medic in two deployments to East Timor and one to Afghanistan, has since qualified as a nurse and works for a Canterbury primary health organisation.

Recalling her experiences in East Timor, she said: “I only realised it had upset me when at the movies years later, and the same sounds [of people wailing grief] in the movie meant I had to leave.”

The Christchurch mother of two returned to Timor-Leste, formerly East Timor, this month with the veteran-led “Back to Timor” group, to re-trace the highways and byways of their deployment more than two decades ago.

‘The families were present and they were wailing and crying and calling out in grief.’

The privately organised group included 15 veterans returning to Timor-Leste to mark the 25th anniversary of the New Zealand Defence Force’s (NZDF) initial deployment there. They visited areas in which they served, pausing to honour those who lost their lives back then and to acknowledge the progress the country has made in the intervening years.

She expected that returning to the area – and particularly the town cemetery – would provoke difficult emotions.

“I’d like to see the locations where good and bad memories were made and hopefully leave the bad ones behind and make some positive ones in their place,” she said.

Collins served a total of about 15 years in the regular and territorial forces from 1997. Afterwards, her rich experience as a medic meant she breezed through a nursing degree.

“I like the medical side of things so wanted to stay in health care,” said Collins. She now works as team lead for immunisation coordination at Pegasus Health, a public health organisation supporting general practices.

East Timor was plunged into violence in 1999, when the population voted in a referendum to become independent from Indonesia. (The colonial power, Portugal, had withdrawn from East Timor in 1974. When East Timor declared its independence in 1975, it was invaded and occupied by Indonesia.)

Following the 1999 referendum, the country was attacked by pro-Indonesian militia. Overall, about 1400 civilians were killed, an unknown number tortured, and women were raped and subjected to other forms of sexual violence. Some 500,000 people were displaced.

A lot of that chaos affected Lolotoe, on the border with West Timor. While some pro-Indonesian militia later stood trial for crimes against humanity, the outcomes were patchy.

NZ part of peace-making taskforce

Between 1999 and 2002, the NZDF deployed more than 5000 personnel to East Timor as part of the International Force East Timor (Interfet), a non-UN peace-making task force to address the unfolding security and humanitarian crisis.

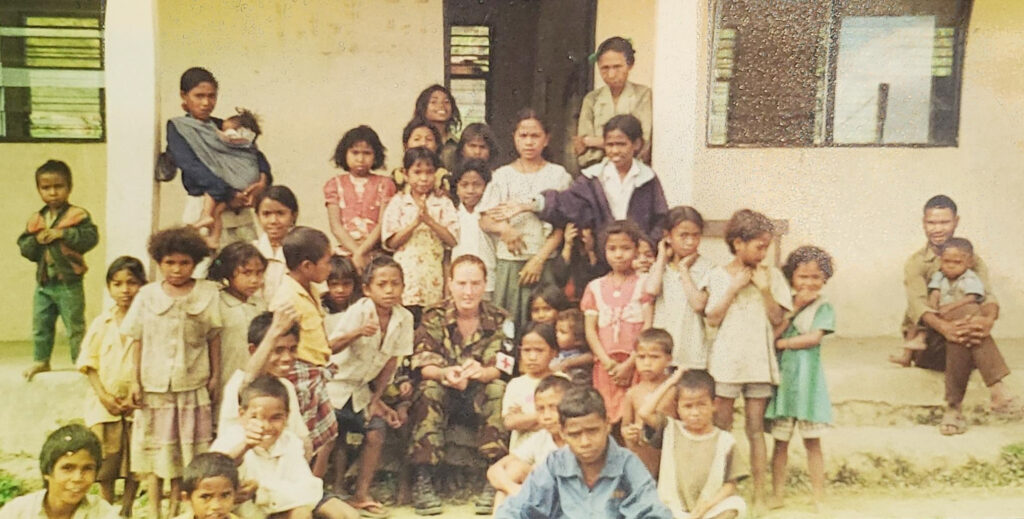

Collins, now aged 46, spent a lot of time as a medic in Lolotoe during her two deployments to East Timor. It was a role that placed her close to the trials and tribulation of locals.

“I remember thinking how destitute the villages looked — dirt roads, some houses with no roofs, dogs everywhere, lots of kids running around with no shoes,” said Collins.

“It was nice how they all waved and called out ‘Bon dia’ [‘Hello’].” With time, she got to know the people, the buildings and the sweeps of the high-country setting well.

‘I remember thinking how destitute the villages looked — dirt roads, some houses with no roofs, dogs everywhere, lots of kids running around with no shoes . . .’

The medical equipment and supplies she had were limited to what she carried, and the priority was treating members of her platoon. She was only allowed to help local people in life-or-limb situations, and then only when approached.

One case she encountered was a local child with seizures from cerebral malaria, who died while being evacuated by helicopter.

Elsewhere, she treated a 61-year-old lady with a bleeding bowel. “I put in an IV, helicoptered her out — had to argue for this! — she had surgery and survived.”

Another case was an unconscious man with arterial bleeding from a machete wound. Collins treated him in the flat bed of a ute and he apparently lived.

“Australians turned us away as [he] was local. Took him to a UNHCR [United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees] clinic we found instead. He was conscious and doing good when we dropped him off.”

In May 2002, East Timor – which is about 500km north of Australia – moved to shrug off its past when it became the first new sovereign state of the new century, the Democratic Republic of Timor-Leste.

“I am really pleased that for the most part, the people of Timor-Leste have been able to live in peace and remain independent,” Collins said.

She was in her early 20s when she deployed to East Timor in 2000 with Batt 2, which was drawn from Burnham-based 2nd/1st Battalion of the Royal New Zealand Infantry Regiment.

“I was attached to an infantry platoon [30 people, roughly] and wherever they went, I would go too,” Collins said.

“This meant patrolling through mountains, jungle or villages with them [if most of the platoon went]. I was responsible for the primary health care and treatment of injuries for those 30 people.”

Collins said the challenges of the climate – cooler high country versus the heat of the lowlands – made it a “difficult balance between having enough water for a patrol so hydration could be maintained, but not too much that it made my pack too heavy.”

She vividly recalls the chronic humidity, the rainy season and the resultant oozing mud that found its way into every piece of equipment, and the experience of living in a clammy tent city.

She vividly recalls the chronic humidity, the rainy season and the resultant oozing mud that found its way into every piece of equipment.

“I remember preferring to be in the smaller outpost camps such as Bobonaro or Gate Pa in the mountains. It was picturesque and the locals seemed happy enough to have us there.

“I thoroughly enjoyed patrolling, especially covert patrols, as it was a slow pace and very peaceful.”

She drank in the contrasts of rice paddies nestled beneath mountain ranges, and remembered the thrill of helicopter rides, versus the depressing low of sleeping on dry, rocky and rat-infested river banks.

‘I thoroughly enjoyed patrolling, especially covert patrols, as it was a slow pace and very peaceful.’

The patrols Collins was on did not come in contact with armed, pro-Indonesian militia groups who infiltrated from West Timor, but the New Zealanders were nonetheless well aware of the danger they posed.

Several deaths – Kiwi soldier Private Leonard Manning and Nepalese soldier Private Devi Ram Jaisi, both killed in action, and Irish soldier Private Peadar O’Flaitheara, accidently killed – were stark warning of the potentially high stakes at play, as was the death of a local child at Belulik Leten.

Overall, Collins said she remains proud of her deployments to East Timor, and was looking forward to returning and seeing the progress that the country has made.

“My first trip especially tested me both physically and emotionally and made me a stronger person.”