I undertook my nursing education at Tauranga Hospital in the late 1970s. While I learnt a lot, often this was by trial and error. Repeatedly — despite our junior student nurse status — we were placed in positions of great responsibility without senior leadership.

We faced unexpected and complex situations that required not only the art and skill of nursing, but essential in-depth knowledge to guide our practice – knowledge we lacked. All the while working seven and 10-day shifts, often in close succession.

If we truly see Māori nurses as taonga, then we need to look at how we do things differently.

Yet, the romanticisation of hospital training prevailed for at least the first 20-30 years of nursing in the tertiary sector. Yes, in considering a move to campus-based training, there were all the arguments about lack of exposure to clinical practice. But there were flaws in the hospital training that frequently led to less-than-desirable outcomes and burnout.

When I entered nursing education in the tertiary sector in the mid-1980s, I came to fully appreciate its importance for nurses. It provided a depth of knowledge we had not previously been exposed to.

I was fortunate to work at the former Waiariki Polytechnic in Rotorua in the first year of its diploma in nursing. We had a revolutionary curriculum framework based on the late Rose Pere‘s Te Wheke concept of holistic health. It was a privilege to work with forward-thinking educators like Bill Brislen, Mere Balzer and others. They understood the need to include cultural safety in nurse teaching. This was prior to its wider emergence at the beginning of the 1990s.

Māori nurse educators were — and are — strong advocates for improving opportunities for Māori to become nurses.

Later, in my post-graduate nursing education work and as education advisor for the Nursing Council, I came to fully appreciate the role of nurse educators in the tertiary sector — and the potential nurses have to make a difference for whānau across Aotearoa.

Māori nurses critical

But we cannot celebrate 50 years of nursing education in the tertiary sector without addressing the elephant in the room and thinking about what we must do moving forward. I say this in my twilight years.

The reality is that Māori are more likely to die younger than non-Māori. We live in what should be the prime of our lives with diseases of older age.

The role of the Māori nurse is critical to improving equity and outcomes for our people.

Having lived through that, we were ahead of our time and, socially, the country wasn’t ready.

Cultural concordance is a huge factor in health outcomes. You look like me, so you’ll look after me and “get” some of my issues — people feel safe to talk and share their stories, trusting that a Māori nurse or health professional will better understand their realities.

Yet we are in the fifth decade of talking about the need to increase the Māori health workforce — especially nurses, who form the largest part of that workforce.

Māori have remained at just six to 7.5 per cent of the nursing workforce for the last four decades. No real change has been made in achieving a Māori nursing workforce that reflects the proportion of Māori in our population — 17 per cent as of August 2022. In some regions the Māori population is even higher, ranging from 20-50 per cent.

The rise of cultural safety — and its dilution

In the 1980s, Hui Whakaroranga was a historical event, gathering government officials, non-government and community health organisations and health workers to listen to the aspirations and concerns of Māori — and define what health meant to Māori. Māori articulated the need to address inequities in health care — a challenge that remains today — and the need for a health workforce to reflect the population it serves.

Equity is not about equality but rather doing things differently for some groups to achieve similar or the same outcomes as others. It is about need, not ethnicity.

Nurse leaders and educators . . . are complicit in the long-standing Māori health inequities, upholding systemic practices deemed to be racist.

Working with our whānau reinforces for me that, for many, health and social needs are enormous. This is a population whose needs are not being met by a health system which is designed to serve people equally when a more tailored response is needed.

The intention may be good — but the way it plays out for Māori and Pacific populations is not working. The outcomes are not equal.

Many whānau do not trust or feel safe in the system — nor with some who work within it. Instead of having their needs met, they experience racism and discrimination. This is where Māori nurses are well-placed to make a difference.

While at the Nursing Council, I was privileged to work with cultural safety pioneer Dr Irihapeti Ramsden. She advocated for new ways of doing things and her legacy — along with that of many other Māori nurses involved in its birth and implementation — is kawa whakaruruhau, which later became known as cultural safety.

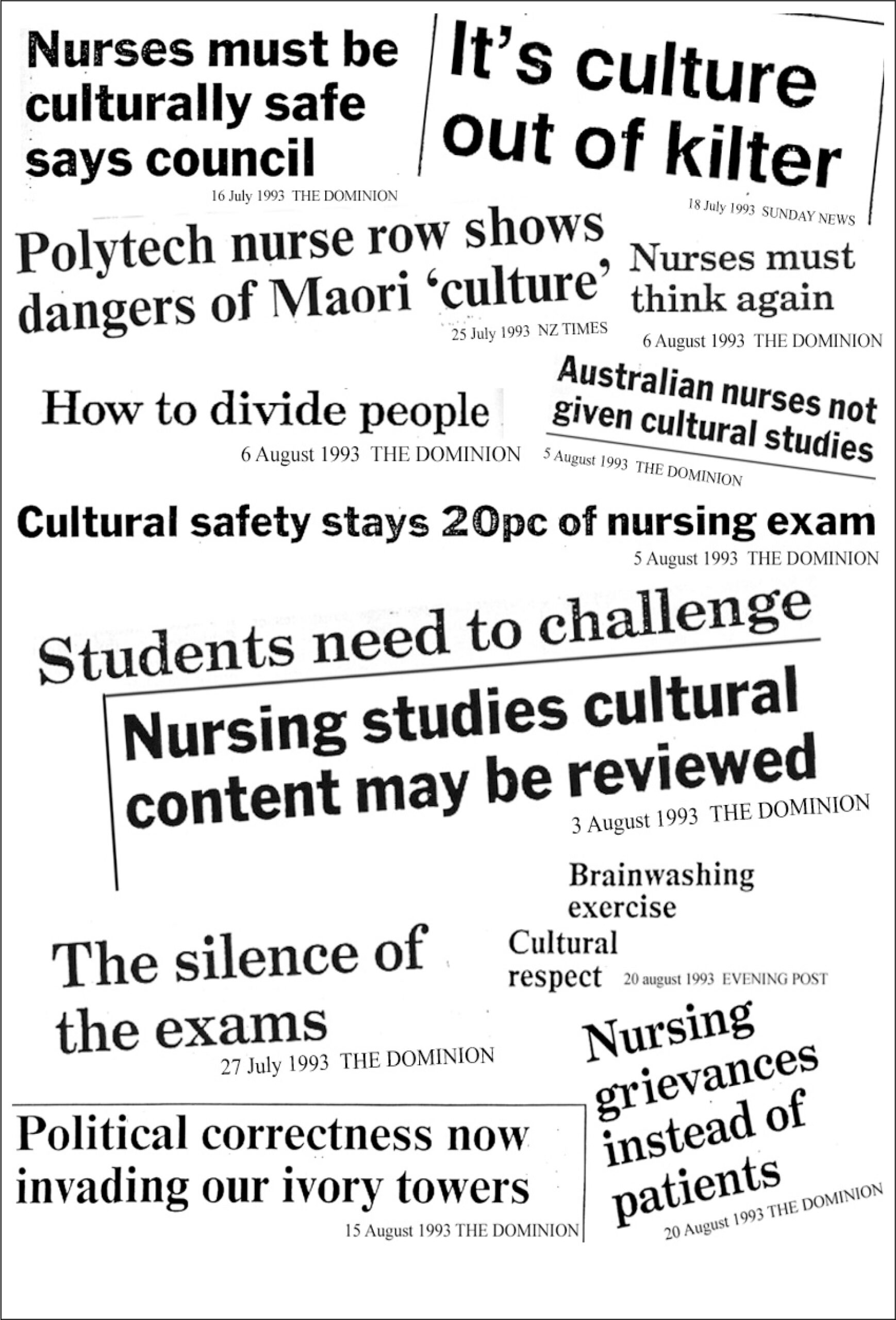

By the early 1990s, cultural safety had become part of the state exam for registered nurses. But the public of Aotearoa rebelled over “political correctness”, leading to a media outcry and parliamentary committee hearings.

Having lived through that, we were ahead of our time and, socially, the country wasn’t ready.

I’ll go to my grave remembering what an ugly time that was to be a nurse educator — to have something that was about trying to improve quality of care and experience, not only for Māori but for everybody, become so challenging.

A subsequent government-initiated review of how cultural safety was being taught resulted in the original concept of kawa whakaruruhau being diluted into a broader concept embracing age, gender and socio-economic status, alongside ethnicity.

Kawa whakaruruhau had been very focused on the safety of Māori and our whānau entering the health system, along with the safety of Māori nurses and tauira (students) as they studied nursing.

I believe its politically-driven broadening into cultural safety has allowed apathy in adopting it as a fundamental nursing concept.

The courage of Māori nurses who introduced kawa whakaruruhau in the late 1980s and early 1990s needs to be reflected on — as does where we go now.

Nurse leaders and educators have languished in unfulfilled rhetoric. They are complicit in the long-standing Māori health inequities, upholding systemic practices deemed to be racist, according to the 2019 Waitangi Tribunal health services and outcomes inquiry (Wai 2575) and Health and Disability System Review. Such discriminatory practices might include rigid clinic hours which do not recognise the realities of whānau work obligations.

Inequal health outcomes for Māori

The courage of Māori nurses who introduced kawa whakaruruhau in the late 1980s and early 1990s needs to be reflected on — as does where we go now.

All nurses have huge potential in this space and are key to a future with accessible, equitable and quality care for whānau and families who are marginalised and prone to poor outcomes due to problems accessing health care.

At the end of the day, all people — but particularly tāngata whenua who continue to endure such poor health outcomes — have the right to access the health system at its various points and come away feeling okay.

The challenge now is for nurses in relatively privileged positions to address their roles in the issues facing whānau Māori, and others marginalised by the health system.

Window-dressing responses, such as using kupu Māori, whakataukī, and tikanga are insufficient to effect change.

Māori nurses are taonga — give them a voice

If we truly see Māori nurses as taonga, then we need to look at how we do things differently. That means people might have to give up something they’re used to doing and give it to someone else. We need to make the space for our Māori nurses to have a voice at all tables seeking solutions to grow our workforce.

It is also time for some hard reflection on the paternalistic “we know best” attitudes and behaviours within nursing that have effectively silenced Māori nurses wanting leadership.

Window-dressing responses, such as using kupu Māori, whakataukī, and tikanga, are insufficient to effect change. Having a Māori nursing workforce that reflects the population is critical to improving equity in outcomes and whānau Māori satisfaction when they engage with health services.

Hamiora Hei (Te Whānau-a-Apanui) — the sister of Ākenehi Hei, one of the first Māori nurses registered — said in a 1897 kōrero to the Te Aute College Students Association that: ” . . . a scheme to train Māori women to tend the sick and to give advice on matters of hygiene, would strike at the root of many evils. It would work below the surface with little trumpeting of its methods . . . and would tend to the increase of the numbers of the race’ (McKegg, 1992, p. 145).

Despite a lot of rhetoric, little has changed.

Kawa whakaruruhau and cultural safety is about people’s dignity, mana, and the essence of humanity.

I am a strong advocate for improving the health and wellbeing of our whānau, hapū, iwi and hapori Māori, and will lay a wero (challenge) going forward. Kawa whakaruruhau and cultural safety is about people’s dignity, mana, and the essence of humanity. Its absence in our people is evident in poor health status, outcomes and determinants.

All health professions need to be culturally safe. Whānau need to know they can expect high quality and culturally safe care. Māori nurses are pivotal in this — they are not nurses who happen to be Māori, they are Māori who happen to be nurses. They bring with them innate knowledge and skills such as relational care, whanaungatanga, manaakitanga and aroha, and can be tika [correct] and pono [dependable] in their practice with Māori.

I have observed a lack of understanding of the taonga status and the mana of Māori nurses and what they offer in nursing education and practice.

I see talented, enthusiastic, and visionary young Māori nurses around me — they are the beacons as we progress into the future.

Space must be given to Māori nurses to lead the way in creating a korowai of kawa whakaruruhau, not only for our Māori nurse educators but, also for whānau, hapū, iwi and hapori Māori. I see talented, enthusiastic and visionary young Māori nurses around me — they are the beacons as we progress into the future.

Health practitioners and nurses are critical in safely caring for our whānau facing social and health challenges. So, while we have challenges moving into the next 50 years, I see great potential, hope, and a growing understanding among nurses in general.

My wero is for nursing education to have the courage to enable Māori leadership going into the next 50 years.

Kia hora te marino, Kia whakapapa pounamu te moana,

Kia tere te Kārohirohi I mua I tōu huarahi.

May the calm be widespread, may the ocean glisten as greenstone.

May the shimmer of light ever dance across your pathway.

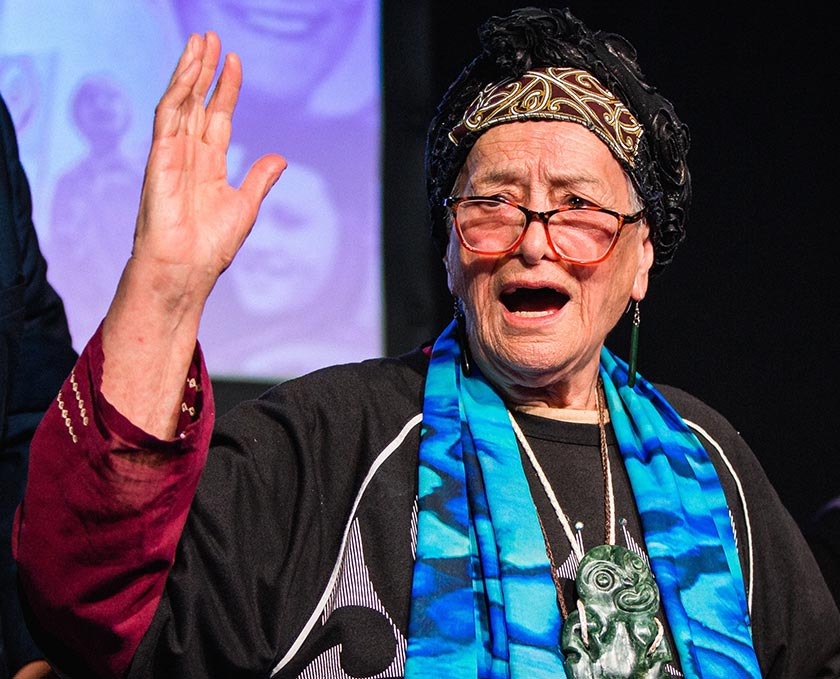

Denise Wilson (Tainui, Ngāti Porou ki Harataunga, Whakatōhea, Ngāti Oneone, Ngāti Tūwharetoa) RN, MA, PhD, is associate dean Māori advancement and professor of Māori health at Auckland University of Technology.

— This article was adapted from Denise Wilson’s kōrero in June, at the 50-year-celebration of nursing education in the tertiary sector and a recent interview with Kaitiaki Nursing New Zealand.

Listen to RNZ’s Kim Hill interviews with Irihapeti Ramsden about cultural safety in nurse training in 1993 and 1995.