* Reading this article qualifies as 30 minutes of CPD.

Key points

Written for a broad primary health care audience, including nurses, this article helps health professionals navigate youth mental health by providing information about:

- distinguishing between mental wellbeing, distress and disorder

- tools and questionnaires that help you make a good mental health assessment, formulation and diagnosis

- where young people can find support

- the importance of relationship-building

- the roles of health coaches, peer support workers and health improvement practitioners

- the range of management options and delivery modes

- when a referral should be made to a specialist mental health service.

Case scenario

Laura checked her clinic list and sighed. Running 10 minutes late into her afternoon list wasn’t too bad in the big scheme of things, but next up was Zoe, a 15-year-old whom she had been seeing weekly for a month.

Although Zoe had initially presented with poor sleep and worries about a relationship breakup, she was now also missing many days of school, not attending her beloved netball team’s games and spending most of her time in her bedroom.

Despite coming to Laura’s clinic for counselling, Zoe was adamant that she did not want her parents to be contacted about her problems because they had been unsupportive in the past. During her last appointment, Zoe disclosed that she had begun cutting her arm when she felt overwhelmed.

When asked directly, she also admitted to occasional, but not strong, thoughts about wishing she was dead. Laura considered what she should do to help Zoe – should she continue to offer her counselling, should she speak to the clinic’s GP about prescribing antidepressants, or should she try and refer her to the overburdened local child and adolescent mental health service (CAMHS)?

With all these thoughts running through her mind she walked to her office door and, with a warm smile, invited Zoe into her room.

The spectrum of mental health

Consultations such as the one introduced by Laura above are typical. Still, for many practitioners they remain challenging due to the variety of ways in which young people present with mental health issues and the range of treatment options and services they may require.

Before considering these in greater detail, it is useful to define some key terms and to consider how mental health is a dynamic spectrum that ranges from a state of wellbeing, through mental distress to mental disorder or illness.

Any of us can be at any of these stages at any time and we can also move to a different stage by doing (or being supported to do) things that are helpful or unhelpful.

Wellbeing

Wellbeing is defined by the World Health Organization (WHO) as a state in which an individual realises their own abilities, can cope with the normal stresses of life, can work productively and is able to contribute to their community.

Although historically construed as merely the absence of illness, it is now recognised as a distinct and complex phenomenon, related to resilience and health literacy, and affected by individual and environmental factors.

Culture also has an impact on wellbeing; non-exclusive examples being whenua (land) and moana (ocean/sea) providing sustenance and spiritual connection for Māori, spirituality being of great importance to Pasifika and collective identity being valued by Asian peoples.

Cultural expressions of wellbeing

Intergenerational influences, including colonisation, can have less visible, yet significant effects on individual wellbeing. For young people, family and school connectedness have been shown to be important for wellbeing.

In Aotearoa New Zealand, information about young people’s wellbeing has been collected for the past couple of decades via the high-school-based Youth 2000 series of studies.1 Although previously stable, wellbeing was found to have declined prior to the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic (from 78.2 per cent in 2007 to 69.1 per cent in 2019), especially among female and Pasifika students.

For more information about wellbeing, check out the Mental Health Foundation page.

Mental distress

Mental distress (also known as psychological distress) is an unpleasant emotional state that is usually transient and often occurs in response to stress or life events.

Commonly, people experience non-specific symptoms such as troubled thoughts, anxiety, low mood and poor sleep. They may also change their daily routines and relationships with people around them.

Rates of mental distress have increased among young people since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Mental distress may range in intensity from unpleasant to profound anguish, and the latter may lead them to use self-harm as a coping mechanism. Despite this, many people with a significant degree of distress may not meet criteria for a diagnosable mental health condition.

Rates of mental distress have increased among young people since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, with more young people presenting for support to school counsellors, engaging in self-harm (eg, rates of presentation to emergency departments increased by 150 per cent at the peak of the pandemic) and being referred to Child and Adolescent Mental Health Services (CAMHS) for assessment.

Management of mental distress

Counselling and talking therapies (eg psychotherapies) can help people make sense of their experiences, address underlying stressors and develop useful coping strategies for situations that are not easy to alter.

Although medication is not usually indicated (and almost never as a first-line intervention), it may be occasionally useful for people experiencing significant anxiety or sleep difficulties for whom non-medication strategies have not proven helpful.

Mental distress versus mental disorder

The distinction between mental distress and mental disorder may not always be easy to make, especially in young people. It requires sound knowledge about normal development, an understanding of diagnostic criteria for mental disorders, and sufficient clinical skill to adequately engage and obtain clinical information from a young person who may not be used to talking with health professionals.

A HEEADSSS assessment can be a useful tool for obtaining a wide range of information about psychosocial factors affecting a young person’s mental state. More specific questioning about symptoms is needed to identify mental disorders.

To be termed a “disorder”, according to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual version 5 – Text Revision (DSM-5-TR), a person’s symptoms need to be present for a specific length of time and be severe enough to limit their functioning on a daily basis.

As stated above, mental distress is usually transient. Although mental disorders may also naturally resolve, symptoms can last for a much longer time and cause significant distress if untreated.

For example, depressive episodes often resolve within a couple of years, but are associated with increased risk of self-harm and suicide as well as delayed developmental tasks of early adulthood; with treatment, on the other hand, they can resolve within weeks to months.

In addition to confirming a diagnosis of mental disorder, a good mental health assessment should also gather information to understand:

-

- why a person may have been vulnerable to developing a problem in the first place (eg, they have a family history of the same disorder, they have experienced early life adversity or have a specific temperament or personality)

- what might have triggered the problem

- what might have kept it going, and

- what factors might have prevented it from getting worse.

This is called a formulation. While the same diagnosis can apply to many people, a formulation is specific to an individual. Both are important for determining a suitable treatment plan.

Common mental disorders among young people

While almost all mental disorders begin by early adulthood, the most common mental disorders during childhood and adolescence are anxiety disorders and depression. As self-harm and suicide are also common among young people in Aotearoa, these will also be briefly discussed below.

♦ Anxiety disorders

Anxiety is a normal human response to danger. However, if it occurs in the absence of, or disproportionate to, genuine danger and adversely affects a person’s daily functioning (eg, refusal to go to school), it may be termed an anxiety disorder.

Anxiety disorders affect around one in 10 children and young people, and may be classified as mild, moderate or severe. Validated questionnaires such as the Generalised Anxiety Disorder – 7 item scale (GAD-7), the Screen for Child Anxiety Related Disorder (SCARED) and the Multidimensional Anxiety Scale for Children 2nd Edition (MASC 2) can also be used to confirm symptoms. The most common types of anxiety disorders in this age group are:

- separation anxiety – worries about separating from caregivers, especially among younger children

- generalised anxiety – worries about multiple issues at home, school or elsewhere, usually in older children

- social anxiety – worries about performing or being seen in public, primarily in teenagers.

Treatment of anxiety usually involves talking therapy (most commonly cognitive behaviour therapy — CBT) to help people understand how anxiety works, what might set off their anxiety and how to change their responses.

Newer electronic (e-) therapies have also been developed and are now recommended as first-line interventions for mild to moderate anxiety disorders.2 If these are not effective, or anxiety is so severe that a child or young person cannot usefully engage in talking or e- therapies, anxiolytic medication (usually a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) such as fluoxetine) may be indicated.

♦ Depression

While everyone feels sad from time to time, depression, otherwise known as major depressive disorder, is a state in which one feels low in mood, loses interest in things that one usually enjoys (anhedonia) and experiences specific cognitive and physical symptoms for more than two weeks.

Like anxiety disorders, depression affects around one in 10 young people and may be classified as mild, moderate or severe, based on the number of symptoms present and level of functional impairment (the extent to which it gets in the way of important day-to-day activities).

While adults often experience sustained low mood and difficulty sleeping, young people may experience fluctuating low mood (often better around peers, worse when alone) and excessive sleeping.

Validated questionnaires such as the Child Depression Inventory version 2 (CDI-2) and Kessler 10 scale can also be used to confirm symptoms. We now know that even mild depression during adolescence can predict symptoms continuing to adulthood and recurrent episodes of mood disorder during adulthood; therefore, it should be identified and treated.

Depression often co-occurs with anxiety, but fortunately, the treatments for both are similar.

Recommendations for the treatment of depression are influenced by its level of severity, which in turn hinges on the number of depressive symptoms (five connotating mild depression, six to eight moderate and over eight indicating the severe end of the spectrum) and the degree of resulting functional impairment.

While adults often experience sustained low mood and difficulty sleeping, young people may experience fluctuating low mood (often better around peers, worse when alone) and excessive sleeping.

First-line treatment of depression (of any level of severity) may include supportive counselling, stress management, physical activity and brief psychological interventions. These are more likely to work if a therapist has a good relationship with the young person.

In addition, addressing life events or adversities that may be precipitating or prolonging the symptoms can also be helpful. If available, structured psychological interventions such as CBT, interpersonal therapy (IPT) and acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT) are all potentially excellent interventions. These may be delivered in person, online or as e-therapies (eg, SPARX).

It is also important to consider when to (or not to) prescribe a psychotropic medication. Prescribing such a medicine is not inherently wrong by any means; in fact, for many this can be lifesaving when undertaken in a considered manner.

Whilst antidepressant medication does not work for mild depression, for depression that is more severe, antidepressant medication can be significantly beneficial if provided for the right people at the right times.

When talking or e-therapies are ineffective, or if depressive symptoms are so severe that a young person cannot gain full benefit from them, antidepressant medication (usually an SSRI such as fluoxetine) may be indicated.

Data recently released by He Ako Hiringa reveals that approximately one in eight young people (aged 12–25 years) had at least one psychotropic medication dispensed in the last 12 months. Between 2019 and 2022, commonly used antidepressants in young people increased from 1 per cent to 4 per cent in those aged 14 to 17, and 7 per cent and 10 per cent in those aged 18 to 25.3

. . . for depression that is more severe, antidepressant medication can be significantly beneficial if provided for the right people at the right times.

On the other hand, use of benzodiazepines or antipsychotic medication in this age group should be exceedingly rare (and only after discussion with a child and adolescent psychiatrist).

Regardless of how effective medication is, recurrence of depression is common (between 30-40 per cent within one to two years). Therefore, it is useful to educate young people about depression, help them develop a better understanding of what affects their mood, learn new skills for managing stressful situations in the future and how to identify early warning signs of a recurrence. Whānau involvement can also increase the effectiveness of these strategies.

♦ Self-harm

Self-harm (also known as deliberate self-harm and non-suicidal self-injury) is common among young people, with up to a quarter of those surveyed during the Youth 2000 series reporting they have engaged in some form of self-harm during the past year.

Rates for rangatahi Māori and Pasifika are two to three times those of other ethnicities, and young people from rural and more deprived areas are at greater risk. Common methods of self-harm include cutting, head banging, biting, scratching or burning of skin, pulling out hair or eyelashes, inhaling or ingesting poisonous substances, and overdosing on prescribed medication.

Most individuals who engage in self-harm do so in an impulsive manner, with the aim of managing mental distress or overwhelming life events. For others, these events occur in a more planned manner and in the context of acute mental illness, most notably depression.

Management of self-harm includes education about the connection between triggers, emotions and behaviour.

Self-harm can make people feel better for a little while, but usually not for long. It can also become an unhealthy habit that is hard to break. Young people are often embarrassed about engaging in self-harm and may not volunteer information unless asked. Self-harm can have short and long-term consequences including increased short-term rates of hospitalisation, later anxiety and depression, and three to four times greater rates of completed suicide.

Management of self-harm includes education about the connection between triggers, emotions and behaviour; provision of ideas about alternative coping mechanisms and improving peer and family support. Counselling or more formal talking therapies (eg, dialectical behaviour therapy (DBT) or CBT) may also be useful. Involvement of whānau can also increase the effectiveness of these strategies.

Commercial apps such as Headspace® and Calm® have accessible and appealing, relaxation and mindfulness-based modules that can be used to prevent and manage thoughts of self-harm. Locally developed communication apps such as Village® can help young people learn to reach out to trusted whānau members and peers, and for these people to support them in helpful ways.

♦ Suicide

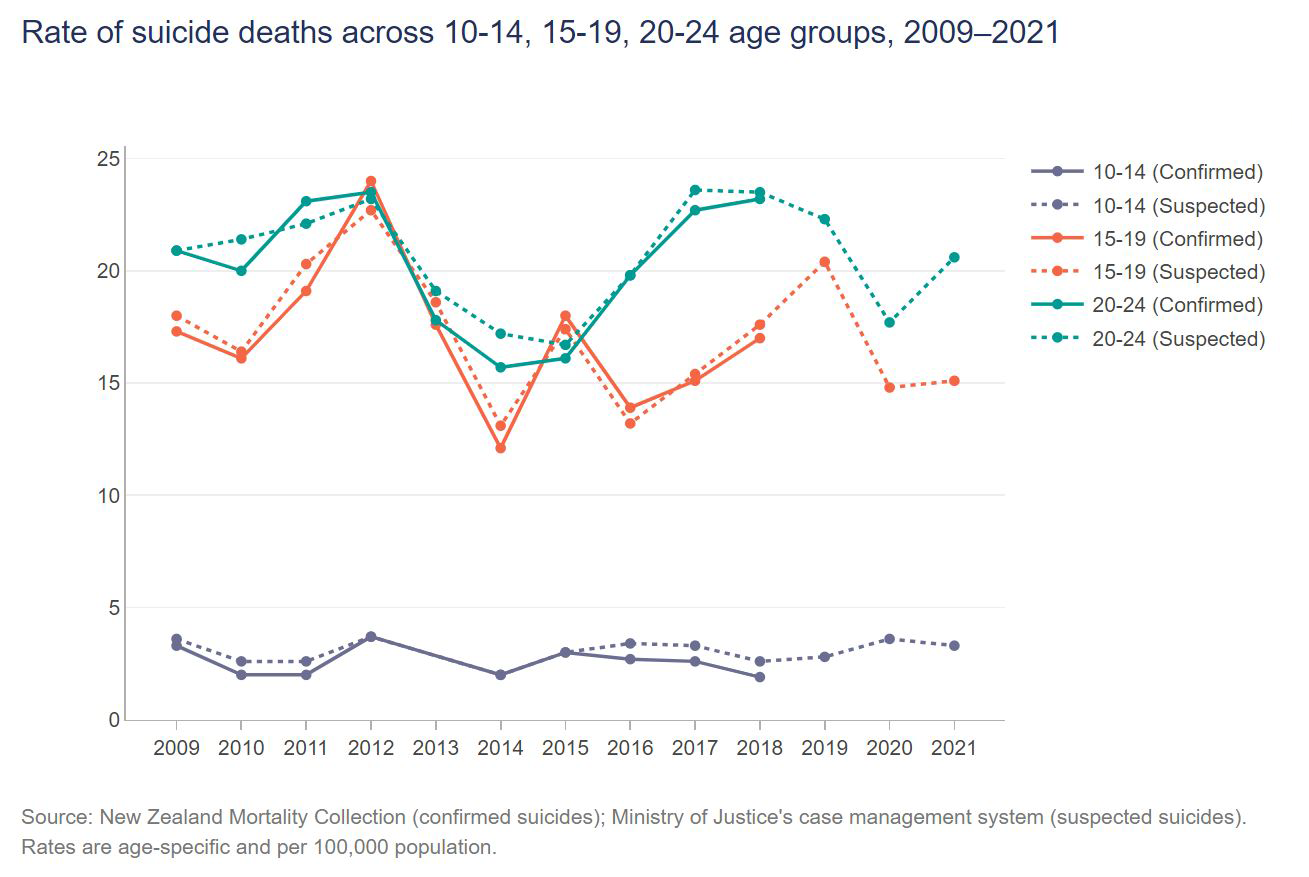

Aotearoa has one of the highest rates of youth suicide in the world (between 15-25 per 100,000 people), with particularly high rates among rangatahi Māori and Pasifika (see Figure 1, below).

Although reasons for this remain unclear, it is possible that individual factors (including previous suicide attempts, family history of completed suicide, association with someone who has recently completed suicide and current mental illness – particularly depression), environmental factors (including relationship difficulties, bullying and poverty) and societal factors (including widespread “she’ll be right” and “harden up” attitudes that limit help-seeking, and colonisation-related disparities) may all play a role.

Enquiring about suicidal thoughts and actions does not increase the risk of suicide and should be sensitively undertaken as part of routine mental health assessment.

However, it should also be noted that, given how rarely suicide occurs, clinicians and risk-related questionnaires are notoriously bad at predicting who will end their life by suicide.

As such, management of identified suicidal thoughts and actions includes immediate safety planning with young people and whānau, routine referral for specialist assessment and follow-up, and further treatment depending on the presence and type(s) of associated mental disorder.

Where can young people get help with mental distress or disorders?

Children and young people primarily receive support from whānau, peers and members of their usual communities (including school counsellors and churches).

When experiencing mental distress or disorder, reliance on these individuals for support will depend on the young person’s previous experiences of help, their own knowledge about prevailing attitudes and prejudices, and their immediate mental state. They rarely present to health services themselves, usually being brought in or referred by others who are concerned about them.

The landscape of mental health services in Aotearoa can broadly be divided into primary health services and specialist mental health services:

Primary health services

- School-Based Health Services (SBHS) – these vary in composition, with most high schools having school counsellors and some having psychologists and visiting GPs.

- Primary health organisations (PHOs) – including GP clinics.

- Non-governmental organisations (NGOs).

- Kaupapa and iwi services.

Specialist mental health services

- CAMHS (child and adolescent mental health service) – funded to see those with the top 3-5 per cent of needs (ie, usually those with severe and/or life-threatening mental illness).

- Private practitioners – usually counsellors, psychologists or psychiatrists who can offer talking therapies and medication.

What are Access and Choice Services?

Following the release of He Ara Oranga: Report of the Government Inquiry into Mental Health and Addiction (2018), the Access and Choice programme was developed, and rollout started in February 2020. Access and Choice builds on mental health and addiction expertise in general practice teams and adds additional staff to services already providing mental health and addiction input.

There is a specific work stream for kaupapa Māori, Pacific and youth primary mental health and substance use services. Funding has also been provided to InsideOUT and Rainbow YOUTH to expand mental health and wellbeing services for takatāpui/rainbow young people.

Within PHOs, health coaches, peer support and health improvement practitioners (HIPs) were offered as part of the Access and Choice programme:

- Health coaches (health navigators, Kaiāwhina or Kaiarahi, community health workers or whānau ora workers) have five roles including self-management support, being the bridge between clinicians and service users, assisting navigation of the healthcare system, providing empathy for the person and ensuring continuity of care. Health coaches generally work with those with long-term conditions and may not have the training to support young people. There is room for the development of health coaches to work specifically with young people with mental health and addiction needs.

- The peer support workforce, also known as the peer, consumer or lived experience workforce, comprises people who have lived or living experience of mental distress or difficulties with substance misuse. Te Pou, the national workforce development agency for adult mental health and addiction, has led the development of a trained peer support workforce, complete with a strategic direction, action plan, values, competencies, training and resources. Whāraurau, the national workforce development agency for infant, child and youth mental health and addiction issues, leads the development and training of the youth peer workforce.

- HIPs are registered health professionals and can be psychologists, nurses, GPs, social workers, psychotherapists, or other health professionals with a mental health qualification. They provide brief interventions (usually one to four sessions) using fACT (a brief version of ACT) and culturally appropriate therapies.

Examples of services that have been specifically tailored for youth are outlined below:

-

- Youth One Stop Shops (YOSS): These services have been available for more than 20 years and provide wrap-around health care for young people aged 12-24. The staff comprise GPs, practice nurses, counsellors, social workers, youth support workers and administrative staff. Some YOSS have specialist mental health practitioners including psychiatrists, clinical psychologists, and alcohol and drug coexisting problems (AOD-CEP) counsellors. Along with sexual health and primary medical care, interventions include individual counselling, various groups (eg, young parents, transgender, rainbow), peer support, assistance with life skills (employment, education, housing, benefits, etc.) and a drop-in or hang-out space. Some YOSS accept walk-ins and others are appointment only. YOSS are known for being youth friendly and engaging well with young people; they all have some level of youth advisory in how the services are developed and continue to run.

- Youth-focused services: There are several youth specific services throughout the country that offer wellbeing care across the age range, with some programmes specifically designed for young people. Many of these services, including Pacific and Māori specific services, received additional Access and Choice The national mental health and addiction workforce development centres, Whāraurau, Le Va and Te Rau Ora provide support and training to improve service delivery and upskill staff to work with young people.

- Fresh Minds: This service in Auckland is part of ProCare Health, the largest PHO in Aotearoa. They offer free or low-cost wellbeing services and receive Access and Choice funding. The staff include registered mental health professionals such as psychologists (clinical, educational, general, health), mental health practitioners, mental health nurses, and social workers.

- The Piki programme: Co-designed with young people and service users, Piki is part of Tū Ora – Compass Health, a PHO providing services in the greater Wellington and Wairarapa regions. It was developed as a pilot programme in 2018 following the release of He Ara Oranga. Piki is noted for its innovative service delivery using peer support, professionals and technology to assist young people 18-25 to overcome adversity and strengthen their wellbeing. Like Fresh Minds, the Piki staff include a range of registered mental health professionals. The Piki service also offers peer support services, through PeerZone, using the Intentional Peer Support model.

What are Child and Adolescent Mental Health Services?

Traditionally called CAFS (child, adolescent and family services) or CAMHS, these secondary youth services are now known as Te Whatu Ora services. Some services include maternal and infant mental health and go by the titles ICAFS (infant, child, adolescent and familiy service) or MICAMHS (maternal, infant, child and adolescent mental health services).

Nationally, almost all secondary youth services offer same day “acute” appointments for young people presenting with particularly high levels of risk. Many services also offer an “urgent” appointment, within a day or two, for those who are not suitable to be waitlisted. In most cases, anybody can refer a person to Te Whatu Ora CAMHS services, and most services will accept self-referrals.

The national KPI (key performance indicator) Programme has waiting time targets of 80 per cent of young people being seen within three weeks of “first contact” (ie, referral letter), and 95 per cent of young people being seen within eight weeks. Most secondary youth mental health services structure their approach using CAPA (choice and partnership approach), a supply and demand model.

The initial “choice” appointment is primarily to understand what brings the young person in and determine which service may work well with the young person and whānau. At this point, the young person and their family may be linked in with another more suitable service, or care will remain with the secondary service and move on to a partnership appointment.

A fuller assessment will be conducted, and a plan developed in collaboration with the young person and whānau, which outlines potential wellbeing options and identifies who will be involved.

Secondary services use a multidisciplinary team approach and generally have a range of registered mental health and addiction staff, including child and adolescent psychiatrists, child psychotherapists, social workers, clinical psychologists, counsellors, nurses and occupational therapists.

All young people are discussed with the team and each member uses their expertise to help guide the care. The teams may have disciplines different to the ones mentioned above (eg, employment specialist, speech and language therapists, youth support workers) and each team will have a range of registered professionals.

When should children and young people be cared for in non-specialist settings?

In general, children and young people experiencing mental distress may be effectively cared for by school-based health services, primary health organisations and non-specialist health services. Those experiencing mild to moderate levels of mental disorder are also likely to benefit from talking therapies in these settings.

Although medication is ideally prescribed in specialist settings, it may be usefully commenced by prescribers if initial approaches (talking therapies) have not been effective, symptoms are worsening or there is likely to be delay in accessing specialist services. Telephone consultation with a child psychiatrist is usually undertaken at this stage.

The importance of relationship building

Photo: iStock Working with young people is often complicated by the very fact that they are young and many of us are not.

We cannot stress enough the importance of engagement and rapport building. Time taken to find out what’s important to the young person and how they spend their time is never wasted; a successful treatment strategy starts with particular founding principles (such as the ideas presented in this article) and must be carefully tailored to the young person and their individual context.

Young people, for a variety of reasons, often do not want their whānau to know that they are sad or distressed, and while we need to respect their confidentiality, use available opportunities to revisit the discussion. Many young people do want the support of their parents and whānau, yet they are afraid of their reactions. Talking through the fears and discussing the value of family support, can assist young people to see things differently.

We cannot stress enough the importance of engagement and rapport building.

Other relationships that are important to both make and sustain are those with services in your area that work with young people, such as YOSS, PHOs and other youth specific services. There are also pharmacists with expertise in mental health and addiction issues who can provide valuable assistance with prescribing options.

Often NGOs effectively provide counselling in many areas, and places such as Catholic Social Services, Presbyterian Support, City Mission, etc, are all around. Consultation with local CAMHS, even prior to making a referral, may help with this orientation process.

A strong network of providers in a local area is often really helpful to draw upon when weaving together a plan for a young person and their whānau at a time when they are feeling most challenged.

When should a referral be made to a specialist mental health service?

Referral to specialist mental health services (usually CAMHS) should be considered in the following instances:

- When there has been no improvement and/or worsening of symptoms with the treatment employed to date, whether this is a talking therapy or a psychotropic medication.

- If multiple issues are identified and need treatment (eg, the ADAPT study found 85 per cent of young people presenting with depression had another mental disorder, especially anxiety or obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD).4

- If acute risk is identified – most commonly this pertains to risk of suicide, with a young person actively thinking about or having recently tried to end their life. It may also include more frequent or severe self-harm, harm to others or harm from others.

Returning to Laura’s clinical dilemma, she’s right to consider referring Zoe to CAMHS. Zoe’s lack of improvement despite ongoing therapeutic work, and her behaviour showing increasing evidence of acute risk are both consistent with situations in which CAMHS involvement may be beneficial.

Hiran Thabrew is a child and adolescent psychiatrist, a paediatrician and director of Te Ara Hāro, the Centre for Infant, Child and Adolescent Mental Health, University of Auckland.

David Chinn is a consultant child and adolescent psychiatrist for the Infant, Child, Adolescent and Family Service (ICAFS), Mental Health, Addiction and Intellectual Disability Service (MHAIDS), Te Whatu Ora; he is also a clinical senior lecturer in the Department of Psychological Medicine, University of Otago.

Karin Isherwood is a senior consultant clinical psychologist and senior advisor at Whāraurau, the national mental health and addiction workforce development centre for infant, child, youth and whānau.

Options for recording your CPD activities and hours include:

- the Nursing Council’s MyNC “continuing competence tab”

- the council’s “professional development activities template” (you can download a PDF from this page)

- the app “Ascribe” which can be found on Google Play or the App Store.

References

- Sutcliffe, K., Ball, J., Clark, T. C., Archer, D., Peiris-John, R., Crengle, S., & Fleming, T. T. (2023). Rapid and unequal decline in adolescent mental health and well-being 2012-2019: Findings from New Zealand cross-sectional surveys. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 57(2), 264-282.

- Wise, J. (2023). NICE recommends digital CBT for children and young people. BMJ, 380, 311.

- He Ako Hiringa. (2023). EPiC dashboard: Youth Mental Health.

- Goodyer, I. M., Dubicka, B., Wilkinson, P., Kelvin, R., Roberts, C., Byford, S., Breen, S., Ford, C., Barrett, B., Leech, A., Rothwell, J., White, L., & Harrington, R. (2008). A randomised controlled trial of cognitive behaviour therapy in adolescents with major depression treated by selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors. The ADAPT trial. Health Technology Assessment, 12(14), iii-iv, ix-60.