From feeling like bothersome aunts, always going on about hand-washing, IPC nurses have suddenly found themselves in hot demand in hospitals and health care across the world, since the COVID-19 pandemic, Auckland IPC nurse specialist Justine Wheatley says.

“IPC has been brought to the forefront, from being a somewhat tedious aspect to a crucial part of everyone’s daily practice,” Wheatley said. “It’s been really cool to see the change in people saying ‘she’s going to tell us to wash our hands again’, to everyone wanting to do their best.”

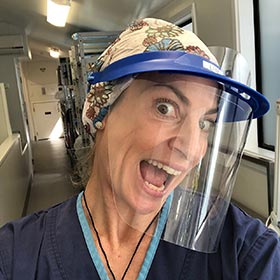

A nurse for 29 years, Wheatley has been an IPC nurse specialist for the past nine of them. She was one of the first graduates of Toi Ohomai’s master’s degree in IPC in 2019, after completing a postgraduate diploma in public health at the University of Auckland in 2016.

She works across two Auckland private hospitals, where IPC nursing staff are involved in everything from mapping out the cleaners’ daily regime to checking management plans and procurement of personal protective equipment (PPE). “I’ve been checking all the face mask samples coming in. I even had to cut them up to see if they had the layers of protection they said they had.”

While it was nice to be appreciated, it could be draining being at the forefront of a pandemic. “It’s pretty overwhelming, everyone wanting you to be everywhere at the same time,” Wheatley said. “From being in the background, now we’re having to be involved in everything. I’m coming home really late and really exhausted, as all essential workers will be able to relate to,” she said.

Hospital processes have been constantly changing since the arrival of COVID-19, and IPC nurses are heavily relied on to ensure the updates are understood and applied. “There is a lot of anxiety. I have to stay really calm for everyone, reminding them they already have all the skills they need,” says Wheatley. But collegial support helped – and they all vent their stress behind closed doors.

“We in the management team looked after each other, we had to be strong for everyone – there have been people crying in the office.”

Fortunately alleviating anxiety is one of her skills, acquired during 12 years working in the United States, where she travelled as a new graduate in the early 1990s. Picking up work in neurology in Miami, then as a multiple sclerosis (MS) clinical nurse specialist in New York Hospital’s Cornell Medical Centre (Judith Jaffe MS Centre), Wheatley found she had a natural ability to de-escalate people’s anxiety and nurture the nurse/patient relationship.

This grew into a love of sharing information and best practice with both colleagues and patients. “I just love discussing things and educating people.”

Emotions as part of practice

Wheatley has deliberately allowed her emotions to become part of her practice and education role, believing it makes her more effective, as both a nurse and teacher. “It’s hard to make it personal and emotive. But giving that feedback in a constructive way brings it back to how our practice affects people’s lives.”

She went on to work at New York University, where she was heavily involved with setting up and coordinating a specialist MS clinic – Langone’s MS Comprehensive Care Center – before returning to New Zealand in 2006 with her young daughter.

The personal approach she now brings to her IPC role, which is a hugely educative one. “I try to drive home how important IPC is to people’s lives.”

And people are listening. “It feels like we are all on a level playing ground in our team of five million,” Wheatley said. “It feels like more like partnership, from the kitchen, to the cleaners to the medical specialists – they all want to do their best. They don’t want to take things home to their families.”

Nor is IPC just one thing – it’s many things, performed repeatedly. That includes physical distancing, patient screening, hand and surface hygiene, along with appropriate PPE being donned and doffed correctly.

Wheatley said she found it surprising to discover how complacent some staff had become to transmission-based precautions, such as droplet spread. But staff were keener now to double-check their processes, constantly seeking out IPC nurses for guidance. “People are really paying attention.”

Even in private hospitals, primarily dealing with elective surgery, people were scared.

“You want to create a culture where preventive behaviour is embedded in everyday practice. I don’t want to be the IPC police. I just want to be a facilitator of good IPC behaviour.”

Wheatley demonstrated how to wear face masks correctly on Television New Zealand’s Seven Sharp last August.

She acknowledges colleagues in district health boards (DHBs) are having a much tougher time than the private sector.

“DHB IPC nursing teams have just had it so hard, and I have seen many of my colleagues breaking down under the pressure – it’s relentless.”

And her former colleagues in New York have shared their struggles too. The city has been “destroyed” by the pandemic, with city occupancy plummeting as residents depart.

Even IPC nurses became a bit “COVID complacent” during the recent long period at level one, but the latest cases of community transmission were a stark reminder of the importance of practising infection prevention consistently.

One of the biggest problems was people washing their hands, then touching their face. People can touch their faces about 40 times an hour and it was a “huge ask” to change such behaviours. “It’s really hard. We’re all human.”