The depressed or anxious patient who comes to see their general practitioner (GP) may be given the option of a prescription medication, but often very little else. Talking therapy is increasingly offered; however, there is often a waiting list and at times there are challenges in finding the right fit for the person. There is also the issue of whether it will be funded – either through GP provider services, employee service providers or Accident Compensation (ACC).

A mildly depressed or anxious individual who isn’t at risk of self-harm or suicide doesn’t need crisis input, may not need long-term psychotherapy or the type of intensive care that a community mental health centre (CMHC) would provide. However they could benefit from some practical strategies and support to improve their mood and well-being.

Psychiatry within conventional medicine has previously had little to offer the individual when it comes to preventative and interventional mental health strategies. While people are regularly exposed to “eat 5+ a day” and “quit smoking” strategies to improve physical health, there has been little attention paid to mental health and well-being.

The Mental Health Foundation has “Five Ways to Well-being” (give, connect, take notice, keep learning and stay active), but even these are not often taught to people who first present with mild symptoms of mental illness and some of these strategies may be difficult to implement.

Nurses in primary and secondary care are in a perfect position to provide short-term intervention to people who suffer from mild mental health disorders…

Part of a model of prevention is having people get the right care at the right time. We know that there are many factors which contribute to a person’s mental well-being and we know that early intervention – including support and the right practical tools – will often enhance the resolution of a mental health issue.1 Nurses in primary and secondary care are in a perfect position to provide short-term intervention to people who suffer from mild mental health disorders, either while waiting for an appointment with a psychologist or counsellor, or as part of the treatment process itself, without going outside our scope of practice.

So what can you do, as a nurse, to support someone with mild depression and anxiety?

The basics

A listening ear

Never underestimate the power of a friendly face and a listening ear. Even if all you do is listen patiently, this can have incredible power. Sometimes a person just wants to feel heard and sometimes, even in their own story-telling, they come to answers themselves about to what to do next. A good cry, reassurance that you are there for them if they need it, may be enough to support the person through a difficult time.

An explanation

Although we don’t actually have a clear understanding about what causes depression or anxiety, we can explain that:

- it’s not their fault

- depression is usually self-resolving, and

- there are things that they can do to help themselves get better.

It’s important they understand they are not alone and there are many organisations (and people) there to help them.

Additional supports

Offer a phone call every few days to see how they are getting on. Ask if they would like more support from a social worker, budgeting advisor or religious leader (if they are that way inclined). Pull in people around them; sometimes this might mean calling in a friend or family member (with permission).

Attending to self-care

The basics of self-care include eating in a way which nurtures, sleeping and resting as appropriate, and physical movement and breathing in a way which promotes relaxation.2 These are all interventions which can support recovery. Along with these are social relationships, time outside (exposure to sunlight) and attending to basic hygiene. Explaining that improvements in these areas can lead to improvements in their mental health can be very empowering and will make them more likely to engage and take steps to help themselves.

Below are more specifics regarding some of these areas.

Nutrition

Probably one of the least-asked questions in mental health is: “What are you eating?” You might be surprised how many people who present with low mood or anxiety are eating minimally or eating a very nutrient-deficient diet. If minimal food is being consumed, ask whether they are fasting or dieting (which can raise cortisol3 and contribute to anxiety, depression4 and fatigue symptoms) or if it’s simply an issue of having no appetite. Find out what types of foods they are eating – sugar,5 caffeine,6 highly-processed carbohydrates, poor quality food,7 dietary transfats8 and pro-inflammatory9 diets can significantly affect how a person is feeling.

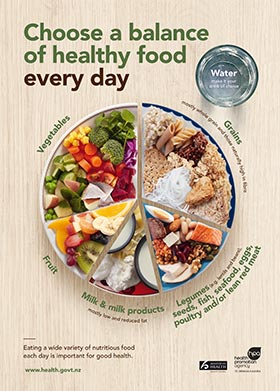

Studies such as the Smiles study10 suggest that changing from a SAD (standard American/Australasian diet) to a Mediterranean-style diet can reduce depression in more than 30 per cent of depressed people. As a nurse (and excluding other health issues which may require specific diets, such as coeliac disease, diabetes etc) you are able to offer basic nutritional advice based on the Ministry of Health11 guidelines (see poster). Encourage a simple but whole food diet (fruit, vegetables, meat, whole grains), as this alone has been shown to help improve mood.12

When asking about diet, be specific – don’t let them tell you their diet is “good” without asking what that means:

- What exactly do they eat for breakfast? When?

- What do they eat for lunch?

- What do they eat for dinner?

- Do they consume energy drinks or soft drinks?

- How much coffee do they drink?

- How much alcohol are they drinking?

- Do they eat carbohydrates, fats and proteins?

- Does their diet have variety?

- Are they following a specific diet (such as vegan or keto) which may be eliminating certain food groups and nutrients?

These may be basic questions, but you will be surprised how far someone can get through the mental health system before anyone asks questions about diet – an important factor for mental health and wellbeing.

Sleep

It’s important to understand the significance of the impact of poor sleep (including sleep apnoea)13 on anxiety, appetite, depression and mood.14 Research has found that poor sleep often precedes mental health deterioration15 and often accompanies depression, anxiety or other mood disorders. People who have experienced nightmares or suffer from post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) often put off going to bed until very late – significantly decreasing their length and quality of sleep.

Ideally, a person should get a minimum of seven to eight hours a night. Less than six hours or more than nine or 10 hours increases the chances of stroke16 and developing metabolic syndrome.17

- Find out when they sleep – are they staying up until 3am and sleeping until 1pm?

- Are their circadian rhythms disrupted?

- How do they feel when they wake?

- Are they waking regularly and not able to return to sleep?

- Do they have trouble getting off to sleep, or wake early?

- Is pain stopping them from sleeping?

They may be able to use sleep strategies (sleep apps, mindfulness, relaxation, breathing exercises or supplements) to support sleep. Encouraging exposing eyes to natural light first thing in the morning stimulates melatonin production to support night-time sleepiness,18 whereas exposure to LED lighting may suppress melatonin.19 Exercising during the day supports sleep at night.20

Other tips may include reducing screen time in the evening, writing down everything that’s on their mind before they go to sleep, ensuring the room is cool and dark and sometimes removing themselves from a snoring partner.

Movement

Exercise has a significant impact on mood and is shown to decrease depression in up to 30 per cent of those who participate.21, 22 Exercising outside may also help vitamin D levels (shown in some studies to be low in more than 90 per cent of people admitted to psychiatric hospitals).23

For those that are exercising, check they aren’t overdoing it. A depressed or anxious person may be driven by the exercise they do as it helps improve their mood – but aren’t eating or resting enough to sustain their energy levels, leading to exhaustion, poor sleep, anxiety and low mood.22

Physical assessment

Assess hair, nails and skin pallor and ask about slow-healing wounds which may suggest a zinc24 or other vitamin deficiency which can affect mental wellbeing.25 Is the person overweight or obese? This can increase inflammation (associated with depression) and is associated with lower vitamin D levels.26 People with diabetes also have a higher risk of becoming depressed.27

Observe their breathing pattern. Are they mouth or nose breathing? Is it shallow, tense? Encouraging deep, relaxed, slow and long belly breaths through the nose can be calming, reduce cortisol levels and help support sleep and relaxation. This type of breathing also has a number of other positive health benefits, including reducing anxiety.1

In some cases, testing can take a look into some of the contributing issues associated with depression. Low vitamin D levels are associated with mental illness,19, 25 while low ferritin/iron levels are associated with fatigue and depression. Low B12, folate and other B vitamins can affect energy levels, memory function and cognition,25, 29 and thyroid disorders can present as anxiety or depression.30, 31 Compare the current blood test to previous blood results – are there significant changes? Is their cholesterol not only not too high – but not too low (associated with low mood)?32 Vitamin levels are often thought to be optimal in the upper range of normal33, 34 (except for ferritin – high levels may indicate other disease states and illnesses).

In some cases, the medication the person is taking may be contributing to their symptoms. Ask if there is an association between starting a medication and onset of symptoms. Are they on medications which may affect their nutrient status? For example, methotrexate can contribute to a folate deficiency,35 statins can reduce CoQ10, diuretics can contribute to a magnesium, calcium or potassium deficiency, Omeprazole reduces vitamin B12 absorption,36 while Accutane has been associated with psychiatric disturbances.37 Also consider the effects of beta-blockers and hormone therapies, including the oral contraceptive pill.36

Supplements and nutrients

Although most nurses can’t prescribe or advise specific treatments, we can look at some of the research available and explain these results to the person. Use evidence-based research, but also be pragmatic. Waiting for a meta-analysis to tell us that a simple intervention is shown to be statistically significant can be a long wait.

There is some good clear evidence on use of omega three fatty acids38, 39 for depression and research on the impact a multivitamin might have for premenstrual syndrome.40 Treating a vitamin D,41 B12 or folate deficiency can have an impact.39, 42

Specific herbs and supplements have been shown to support mood. Ashwaganda and Rhodiola are fantastic to support people under a lot of stress.43 St Johns Wort has good evidence as an antidepressant.44 N‐acetylcysteine has been shown to help with mental health issues.39 Always check for interactions with any medication they may be taking, and ask them to check with their pharmacist or prescribing doctor.

Summary

Nursing is a complex task – and knowing what to do for someone who is anxious or depressed can be challenging. We often want to “refer on” to psychological therapists or to mental health services. However, there is a lot we can do to support the person during this time. We can (and should be) knowledgeable and comfortable providing some basic advice and support, which may mean the difference between a relatively quick recovery and a downward slide into a worsening or chronic mental health condition.

Many patients miss out on techniques, lifestyle advice, dietary changes and tools that might help them take those extra few steps towards wellness. These tools and knowledge may last them a lifetime and help to prevent future relapses.

Helen Duyvestyn, RN, MHSc, AdvDip MH Nursing, PGCert HSc in Adv Nurs, is a clinical nurse specialist in the Department of Psychological Medicine, Middlemore Hospital, and owner operator of One Life (Mental Health and Well-being Services).

References

- McGorry, P. D., & Mei, C. (2018). Early intervention in youth mental health: Progress and future directions. Evidence-Based Mental Health, 21, 182-184. doi.org/10.1136/ebmental-2018-300060

- Ma, X., Yue, Z. Q., Gong, Z. Q., Zhang, H., Duan, N. Y., Shi, Y. T., Wei, G. X., & Li, Y. F. (2017). The effect of diaphragmatic breathing on attention, negative affect and stress in healthy adults. Frontiers in Psychology, 8, 874. doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.00874

- Tomiyama, A. J., Mann, T., Vinas, D., Hunger, J. M., Dejager, J., & Taylor, S. E. (2010). Low calorie dieting increases cortisol. Psychosomatic Medicine, 72(4), 357–364. doi.org/10.1097/PSY.0b013e3181d9523c

- Patton, G. C., Carlin, J. B., Shao, Q., Hibbert, M. E., Rosier, M., Selzer, R., & Bowes, G. (1997). Adolescent dieting: Healthy weight control or borderline eating disorder? Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, and Allied Disciplines, 38(3), 299–306. doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7610.1997.tb01514.x

- Knüppel, A., Shipley, M. J., Llewellyn, C. H., & Brunner, E. J. (2017). Sugar intake from sweet food and beverages, common mental disorder and depression: Prospective findings from the Whitehall II study. Scientific Reports, 7(1), 6287. doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-05649-7

- Bruce, M., Scott, N., Shine, P., & Lader, M. (1992). Anxiogenic effects of caffeine in patients with anxiety disorders. Archives of General Psychiatry, 49(11), 867–869. doi.org/10.1001/archpsyc.1992.01820110031004

- Berk, M., Williams, L. J., Jacka, F. N., O’Neil, A., Pasco, J. A., Moylan, S., Allen, N. B., Stuart, A. L., Hayley, A. C., Byrne, M. L., & Maes, M. (2013). So depression is an inflammatory disease, but where does the inflammation come from? BMC Medicine, 11(200). doi.org/10.1186/1741-7015-11-200

- Golomb, B. A., Evans, M. A., White, H. L., & Dimsdale, J. E. (2012). Trans fat consumption and aggression. PLoS ONE, 7(3), e32175. doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0032175

- Haghighatdoost, F., Feizi, A., Esmaillzadeh, A., Feinle-Bisset, C., Keshteli, A. H., Afshar, H., & Adibi, P. (2018). Association between the dietary inflammatory index and common mental health disorders profile scores. Clinical Nutrition, 38(4), 1643-1650. doi.org/10.1016/j.clnu.2018.08.016

- Jacka, F. N., O’Neil, A., Opie, R., Itsiopoulos, C., Cotton, S., Mohebbi, M., Castle, D., Dash, S., Mihalopoulos, C., Chatterton, M. K., Brazionis, L., & Berk, M. (2017). A randomised controlled trial of dietary improvement for adults with major depression (the ‘SMILES’ trial). BMC Medicine, 15, 23. doi.org/10.1186/s12916-017-0791-y

- Ministry of Health. (2020). Eating and activity guidelines for New Zealand adults.

- Firth, J., Marx, W., Dash, S., Carney, R., Teasdale, S. B., Solmi, M., Stubbs, B., Schuch, F. B., Carvalho, A. F., Jacka, F., & Sarris, J. (2019). The effects of dietary improvement on symptoms of depression and anxiety: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Psychosomatic Medicine, 81(3), 265-280. doi.org/10.1097/PSY.0000000000000673

- Kaufmann, C. N., Susukida, R., & Depp, C. A. (2017). Sleep apnea, psychopathology, and mental health care. Sleep Health, 3(4), 244–249. doi.org/10.1016/j.sleh.2017.04.003

- Riemann, D., Krone, L. B., Wulff, K., & Nissen, C. (2020). Sleep, insomnia, and depression. Neuropsychopharmacology, 45(1), 74–89. doi.org/10.1038/s41386-019-0411-y

- Scott, J., Byrne, E., Medland, S., & Hickie, I. (2020). Short communication: Self-reported sleep-wake disturbances preceding onset of full-threshold mood and/or psychotic syndromes in community residing adolescents and young adults. Journal of Affective Disorders, 277, 592–595. doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2020.08.083

- Ge, B., & Guo, X. (2015). Short and long sleep durations are both associated with increased risk of stroke: A meta-analysis of observational studies. International Journal of Stroke, 10(2), 177–184. doi.org/10.1111/ijs.12398

- Ju, S. Y., & Choi, W. S. (2013). Sleep duration and metabolic syndrome in adult populations: A meta-analysis of observational studies. Nutrition and Diabetes, 3(e65). doi.org/10.1038/nutd.2013.8

- Takasu, N. N., Hashimoto, S., Yamanaka, Y., Tanahashi, Y., Yamazaki, A., Honma, S., & Honma, K. (2006). Repeated exposures to daytime bright light increase nocturnal melatonin rise and maintain circadian phase in young subjects under fixed sleep schedule. American Journal of Physiology, 291(6), R1799-R1807. doi.org/10.1152/ajpregu.00211.2006

- Bauer, M., Glenn, T., Monteith, S., Gottlieb, J. F., Ritter, P. S., Geddes, J., & Whybrow, P. C. (2018). The potential influence of LED lighting on mental illness. World Journal of Biological Psychiatry, 19(1), 59-73. doi.org/10.1080/15622975.2017.1417639

- Yang, P. Y., Ho, K. H., Chen, H. C., & Chien, M. Y. (2012). Exercise training improves sleep quality in middle-aged and older adults with sleep problems: A systematic review. Journal of Physiotherapy, 58(3), 157-163. doi.org/10.1016/S1836-9553(12)70106-6

- Blumenthal, J. A., Smith, P. J., & Hoffman, B. M. (2012). Is exercise a viable treatment for depression? ACSM’s Health & Fitness Journal, 16(4), 14–21. doi.org/10.1249/01.FIT.0000416000.09526.eb

- Chekroud, S. R., Gueorguieva, R., Zheutlin, A. B., Paulus, M., Krumholz, H. M., Krystal, J. H., & Chekroud, A. M. (2018). Association between physical exercise and mental health in 1.2 million individuals in the USA between 2011 and 2015: A cross-sectional study. Lancet Psychiatry, 5(9), 739- 746. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(18)30227-X

- Cuomo, A., Maina, G., Bolognesi, S., Rosso, G., Beccarini Crescenzi, B., Zanobini, F., Goracci, A., Facchi, E., Favaretto, E., Baldini, I., Santucci, A., & Fagiolini, A. (2019). Prevalence and correlates of Vitamin D deficiency in a sample of 290 inpatients with mental illness. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 10, 167. doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2019.00167

- Maxfield, L., & Crane, J. S. (2020). Zinc Deficiency. In StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing.

- Kennedy, D. O. (2016). B vitamins and the brain: Mechanisms, dose and efficacy – a review. Nutrients, 8(2) 68. doi.org/10.3390/nu8020068

- Vranic, L., Mikolaševic, I., & Milic, S. (2019). Vitamin D Deficiency: Consequence or Cause of Obesity? Medicina, 55(9), 541. doi.org/10.3390/medicina55090541

- Deischinger, C., Dervic, E., Leutner, M., Kosi-Trebotic, L., Klimek, P., Kautzky, A., & Kautzky-Willer, A. (2020). Diabetes mellitus is associated with a higher risk for major depressive disorder in women than in men. BMJ Open Diabetes Research & Care, 8(1), e001430. doi.org/10.1136/bmjdrc-2020-001430

- Motsinger, S., Lazovich, D., MacLehose, R. F., Torkelson, C. J., & Robien, K. (2012). Vitamin D intake and mental health-related quality of life in older women: The Iowa Women’s Health Study. Maturitas, 71(3), 267–273. doi.org/10.1016/j.maturitas.2011.12.005

- Mikkelsen, K., Stojanovska, L., & Apostolopoulos, V. (2016). The effects of Vitamin B in depression. Current Medicinal Chemistry, 23(38), 4317–4337. doi.org/10.2174/0929867323666160920110810

- Bathla, M., Singh, M., & Relan, P. (2016). Prevalence of anxiety and depressive symptoms among patients with hypothyroidism. Indian Journal of Endocrinology and Metabolism, 20(4), 468-474. doi.org/10.4103/2230-8210.183476

- Radhakrishnan, R., Calvin, S., Singh, J. K., Thomas, B., & Srinivasan, K. (2013). Thyroid dysfunction in major psychiatric disorders in a hospital based sample. Indian Journal of Medical Research, 138(6), 888-893.

- Sansone, R. A. (2008). Cholesterol quandaries: Relationship to depression and the suicidal experience. Psychiatry (Edgmont), 5(3), 22-34.

- Krzywanski, J., Mikulski, T., Pokrywka, A., Młynczak, M., Krysztofiak, H., Fraczek, B., & Ziemba, A. (2020). Vitamin B12 status and optimal range for hemoglobin formation in elite athletes. Nutrients, 12(4), 1038. doi.org/10.3390/nu12041038

- Smith, D. A., & Refsum, H. (2012). Do we need to reconsider the desirable blood level of vitamin B12? Journal of Internal Medicine, 271(2), 179-182. doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2796.2011.02485.x

- Visentin, M., Zhao, R., & Goldman, I. D. (2012). The antifolates. Hematology/Oncology Clinics of North America, 26(3), 629–ix. doi.org/10.1016/j.hoc.2012.02.002

- Mohn, E. S., Kern, H. J., Saltzman, E., Mitmesser, S. H., & McKay, D. L. (2018). Evidence of drug-nutrient interactions with chronic use of commonly prescribed medications: An update. Pharmaceutics, 10(1), 36. doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics10010036

- Ludot, M., Mouchabac, S., & Ferreri, F. (2015). Inter-relationships between isotretinoin treatment and psychiatric disorders: Depression, bipolar disorder, anxiety, psychosis and suicide risks. World Journal of Psychiatry, 5(2), 222–227. doi.org/10.5498/wjp.v5.i2.222

- McNamara, R. K. (2016). Role of omega-3 fatty acids in the etiology, treatment, and prevention of depression: Current status and future directions. Journal of Nutrition & Intermediary Metabolism, 5, 96-106. doi.org/10.1016/j.jnim.2016.04.004

- Firth, J., Teasdale, S. B., Allott, K., Siskind, D., Marx, W., Cotter, J., Veronese, N., Schuch, F., Smith, L., Solmi, M., Carvalho, A. F., Vancampfort, D., Berk, M., Stubbs, B., & Sarris, J. (2019). The efficacy and safety of nutrient supplements in the treatment of mental disorders: A meta-review of meta-analyses of randomized controlled trials. World Psychiatry, 18(3), 308–324. doi.org/10.1002/wps.20672

- Retallick-Brown, H., Blampied, N., & Rucklidge, J. J. (2020). A Pilot Randomized Treatment-Controlled Trial Comparing Vitamin B6 with Broad-Spectrum Micronutrients for Premenstrual Syndrome. Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine, 26(2), 88-97. doi.org/10.1089/acm.2019.0305.

- Penckofer, S., Byrn, M., Adams, W., Emanuele, M. A., Mumby, P., Kouba, J., & Wallis, D. E. (2017). Vitamin D supplementation improves mood in women with type 2 diabetes. Journal of Diabetes Research, 2017, 8232863. doi.org/10.1155/2017/8232863

- Coppen, A., & Bolander-Gouaille, C. (2005). Treatment of depression: Time to consider folic acid and Vitamin B12. Journal of Psychopharmacology, 19(1), 59-65. doi.org/10.1177/0269881105048899

- Head, K. A., & Kelly, G. S. (2009). Nutrients and botanicals for treatment of stress: Adrenal fatigue, neurotransmitter imbalance, anxiety, and restless sleep. Alternative Medicine Review: A Journal of Clinical Therapeutic, 14(2), 114-140.

- Ng, Q. X., Venkatanarayanan, N., & Ho, C. Y. (2017). Clinical use of Hypericum perforatum (St John’s wort) in depression: A meta-analysis. Journal of Affective Disorders, 210, 211-221. doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2016.12.048

This article was reviewed by Philip Ferris-Day, RN, MMH, a lecturer in the school of nursing, Massey University, Wellington.