Many New Zealanders are more centralist in their view of the governance of society than I am. I come from the tradition that sees local autonomy as a critical part of a democratic society – not to mention its benefits in terms of innovation, responsiveness and dealing with diversity. Sometimes it is necessary to have collective and central solutions to public policy problems, but when I am thinking about their design or evaluation, I never forget a decentralisation perspective.

The current “redisorganisation” of the health system is a shift towards centralisation. I am not inherently opposed to such a shift, but I am concerned we may be over-centralising.

In last month’s article, I concluded we should not be surprised if there are pressures to centralise the system further, even at the cost of the loss of local, and even clinical, autonomy and innovation. This conclusion was underpinned by four general propositions:

- There is an inherent tension between the centre (which funds health care), together with the complex organisations it charges to implement its plans, and what goes on at the clinical and local level of professionals dealing with patients. The tension is unavoidable in a publicly-funded system.

- The complexity of the sprawling health system is substantial. It has been described as a “disorganisation”. Plans to “redisorganise” it need to be humble, aiming for incremental improvements rather than those that are ambitiously neat, plausible and wrong.

- One of the sources of the sprawl in the health system is its historical development from the 19th century system when hospitals were small, not very technically advanced, local and isolated. Medicine then was primitive but not wholly ineffective. Despite the spectacular changes in the following 150 years, there are still fossilised remnants of the old system.

- The centre has made errors, but it generally does not acknowledge them. It is easy to blame the districts for everything. Mistakes are inevitable but failure to acknowledge they can happen will corrupt a planned redisorganisation.

A critique of the proposals

This analysis is based on a (released) Cabinet paper, which sets out a sevenfold justification for the proposed changes.

Māori issues:

The first two justifications concern Māori issues. One is constitutional, arguing that the “public health system does not meet the Crown’s obligations to Māori”. The second is that the “overall system performance” (which the Cabinet paper emphasises is “high”) “conceals significant underperformance and inequity, particularly for Māori and Pacific peoples” (although there is little attention to Pacific peoples’ needs).

This issue requires a lot more teasing out – but not here. The danger is that if we characterise the problem as “Māori”, with little thought about what is actually going on, we shall have an expensive failure. Such concerns are already justified given that those who have welcomed the new Māori health authority have so many different views on what it will do.

The paper admits there is also significant underperformance and inequity for others who are not Māori (or Pacific). It is not obvious that the paper addresses their needs. By focusing on the Māori dimension, the system may fail to identify general problems and continue to leave others behind.

Funding issues:

Justification 7 is that “funding has not increased in line with increasing costs and rising demand”. However, the redisorganisation does not address the funding issue. The transition will add to costs; if the 1990s redisorganisation is any indication, they may be very large. Nor should we be surprised if the new system is more costly to run. Additional layers of management often reduce the productivity of those who deliver services.

Moreover, if we deploy more health resources for Māori health care, as the Cabinet paper argues, and provide more resources to the other groups which the paper mentions as not being adequately covered, this means there will be less for the rest. Are we willing to accept fewer resources for the rest, perhaps compromising their health and wellbeing or pushing them into the private sector?

So the funding issues are not going to go away. At least nobody is making the stupid claim of the 1990s redisorganisation, that this time it will generate substantial cost savings.

Population health issues:

I have little trouble with justification 6, that the “system does not routinely take a population health approach”. Twice in the past three decades there have been attempts to deal with this, and twice the approach has been castrated because of powerful lobbies which profit by ignoring population-based health promotion.

Only insiders appreciate how magnificently our public health profession has responded to the COVID-19 pandemic, performing well beyond what we might expect, despite the gutting of the relevant institutions.

It is easy to reduce the focus of population health policies to the big ones of alcohol abuse, tobacco use and obesity. But, for instance, epidemiologist and public health expert David Skegg has drawn attention to the failure to provide quality water; we also need to prepare for the next pandemic. A wider perspective will reduce the leverage of the lobbies who want to close down advocacy of policies which will decrease their profits.

I add here a criticism of a too-common canard – that better prevention will reduce treatment costs. It may not. For instance, banning smoking increases costs because people live longer – perhaps an extra 10 to 20 years – and will be a charge on the future health system during their longer life. From a health and welfare perspective, we may celebrate that outcome, but from an accounting perspective the ideal is the cigarette which explodes on the day the smoker retires.

The provider capture issue:

Justification 5 says: “. . . services are too often built around the interests of providers, and not around what consumers value and need. Improvements in service design and adoption of new technologies have been sluggish, resulting in little shift of services from hospital to community environments, despite this having been government policy for more than 20 years. Virtual consultations only became common during the height of the COVID-19 pandemic; and since the lowering of alert levels, have retrenched again.”

What this cryptic bureaucratic passage may indicate is the view that health professionals use their political power to divert resources from high priority care to their less important practices – especially from preventative and primary care to treatments.

It is true that some treatments are not as efficient as their proponents argue. There is also a phenomenon called “supplier-induced demand” (SID), when a professional proposes a course of treatment which the funder would not choose if they were fully informed. (Often the SID treatment is to the financial benefit of the promoter, which is why it is a greater problem in the private health sector.)

However, that account is only partial. The main reason resources are used in some areas and not others is that public demand prioritises urgent treatments. It insists, for instance, that inflamed appendices be dealt with immediately.

Perhaps a plodding economist or bureaucrat would do an analysis which showed there were more valuable treatments than the urgent ones and that the higher priorities are being neglected. Perhaps the public, given the information, would agree. But that would lead to the conclusion that there should be more resources.

It is too easy to invent such bureaucratic jargon as in the passage I quoted to divert attention from its real content. The writers ought to provide a jargon-free account of what they actually mean.

System complexity issues:

Justification 3 is that “the system has become complex and unnecessarily fragmented, with unclear roles, responsibilities and boundaries”.

In my first article, I argued that complexity and fragmentation are inevitable. It may be useful to make the traditional distinction between surgeons and internal medicine. The patient arrives at hospital with an inflamed appendix and the surgeon deals with it. The patient arrives at hospital with an internal ache; in the course of the diagnosis the medical team finds they have a host of other problems, including perhaps excessive drinking and not getting on with the spouse. There is no simple remedy, even if the clinicians were certain about what is going on.

Centralisation policies for the health system are usually based on the surgical model, ignoring the complexity and fragmentation clinicians face. Thus they miss the problems identified in justifications 2 (underperformance for certain groups) and 5 (the failure to integrate primary and secondary care). That was what happened in the early 1990s redisorganisation – even the promises of productivity increases reflected a view of health care as a series of a surgical operations.

Do people have a say?

As for justification 4: “the public do not have a consistent say in the operation of the system”, the kindest thing to say about the proposed redisorganisation is that it provides consistency across the public by reducing everyone’s say to zero. It was never great, but under the new system it is going to be less.

We have a health and disability commissioner who does an excellent job of remedying a failure by a health professional after you are dead. However, if the problem is one of various services not interfacing, the commissioner is unlikely to be involved. A stiff letter to the head of the proposed Health New Zealand, which is to supervise the running of the hospitals, will likewise get no remedy.

The proposals hardly elaborate how consumers of health care will have a voice. (The exception may be Māori.) Voice is required at the personal level. Consider those in hospitals (or rest homes) who fall between the cracks because no one seems to be in charge; a problem quickly fixed with goodwill and an effective advocate – if there is one. (I do not think clinicians should fear such a well-designed complaint system, especially if it is built around a no-fault but “fix it” culture.)

Voice at the local level matters too. The likelihood is that rural and provincial communities will feel disenfranchised under the new system. When the folk in Whangārei have a community complaint, they will have to picket in Auckland (or possibly Hamilton) – or even Wellington.

Recall, too that one of the reasons for separating out the Counties-Manukau crown health enterprise (later a district health board) in 1992 was because the Auckland Area Health Board was thought to be underplaying the needs of South Auckland; a similar local concern generated the Wairarapa CHE/DHB. For a locality, a regional centre can be over-centralised.

I have long doubted the effectiveness of elected representatives on the governing boards. Friends with the best intentions who got elected would leave after one term because they felt they had no effect. But they did grumble and they were a part of a system which gave people a feeling they had some say. Because they grumbled, elected representatives were killed off by Parliament one night in 1991; this time they have been neutered – told not to comment.

The public has to have confidence in those whom it asks to take up its cases. Centralised appointments will not be trusted, especially in the regions. There are a number of ways representation can be organised. All should require some local input in the selection.

While I would like to say that the 1990s redisorganisation collapsed because of the severe technical deficiencies of the underlying theories and the resulting implementation failures, probably far more important was the popular uprising against the imposition of what seemed to be a foreign culture of commercialisation by Wellington.

Back to the inherent tension

The usual reason for more central control is the demands of public funding, which pushes the balance away from the patient, the clinician and the local. Thus we see the decades-long efforts to increase central control of the health system. The abolition of the district health boards follows a logical continuation from the limitations of the local hospital boards of the 1950s when the central government took over total responsibility for funding.

Yet, as the central government has got involved, the problem of the increasing fiscal burden has not been resolved. A solution has been to offload on to private health care, but that adds to the inequity of the system. This redisorganisation will not resolve these problems. The danger is that other strengths of the current system will be lost.

Centralisers make mistakes

A major weakness of centralisers is their tendency to design systems on the assumption they never make mistakes. Had they been more realistic, the planned redisorganisation would have observed that some part of the various failures can be attributed to the failure of the centre (Wellington).

In my first article I went through the sad story of the recent Canterbury DHB fracas. I know the centre has never given its side of the story – perhaps it does not want to admit failure.

It is likely that such things will happen again under the new regime. Despite its brilliant handling of the COVID-19 crisis, there is little confidence in the Ministry of Health as one of our better government agencies (at a time when there is much pessimism about the quality of the public service generally). A covert purpose of the redisorganisation may be to improve the functioning of the ministry. If it happens, it will be welcome.

The failure to acknowledge that the centralisers will make errors – grievous errors – is why the designers think there is no need to build the public’s involvement into the new system. Voice is unnecessary if you never make mistakes.

If one never acknowledges mistakes, one never learns from them. There have not only been poor appointments to DHBs but some of the appointments to the ministry itself have also been of poor quality (also true for some ministers). The system also needs to be designed to insulate itself from a minister who is unsympathetic to the principles underlying the system and who systematically undermines them – as has happened. Should we design a system so heavily dependent upon those at the centre?

Of course mistakes are also made at the local level. Good design which accepts they happen makes a decentralised system more robust.

Local innovation

Centrally organised systems are not very good at genuine innovation. DHBs offered the promise of local innovation and experiment, which could then be applied elsewhere (for instance in primary-secondary integration). Experiments may have happened, but usually the lessons did not percolate through the whole system. The shortage of funds inhibited them as boards focused on urgent care. (It is difficult to get GPs to address alcoholism if you are desperately removing appendices.)

Some of the “experiments” are interestingly subversive of the current centralisation proposals. I have a personal interest in paediatric endocrinology. Quite large provincial DHBs may have work for only one specialist; professionally that leaves them isolated. Who can the sole endocrinologist consult on a particularly tricky case? Who provides cover when he or she is on holiday?

One answer has been to build up a collegial network across a number of DHBs. This sounds sensible to me. It suggests that to work properly one needs centres of advanced health-care excellence – in effect a tertiary hospital associated with medical schools together with a remit to support a set of identified secondary providers.

The role of medical schools in the system is hardly touched on, in part because universities are allergic to central direction. But the schools are repositories of much knowledge, not only about hospital medicine, but about public health, care of the elderly and disabled and primary care.

You may wonder whether the proposed four regional offices for Health New Zealand are such centres of excellence. That is not the intention. Their purpose is funding and governance, not provision. They are more an echo of the later-discarded regional health authorities of the 1990s redisorganisation.

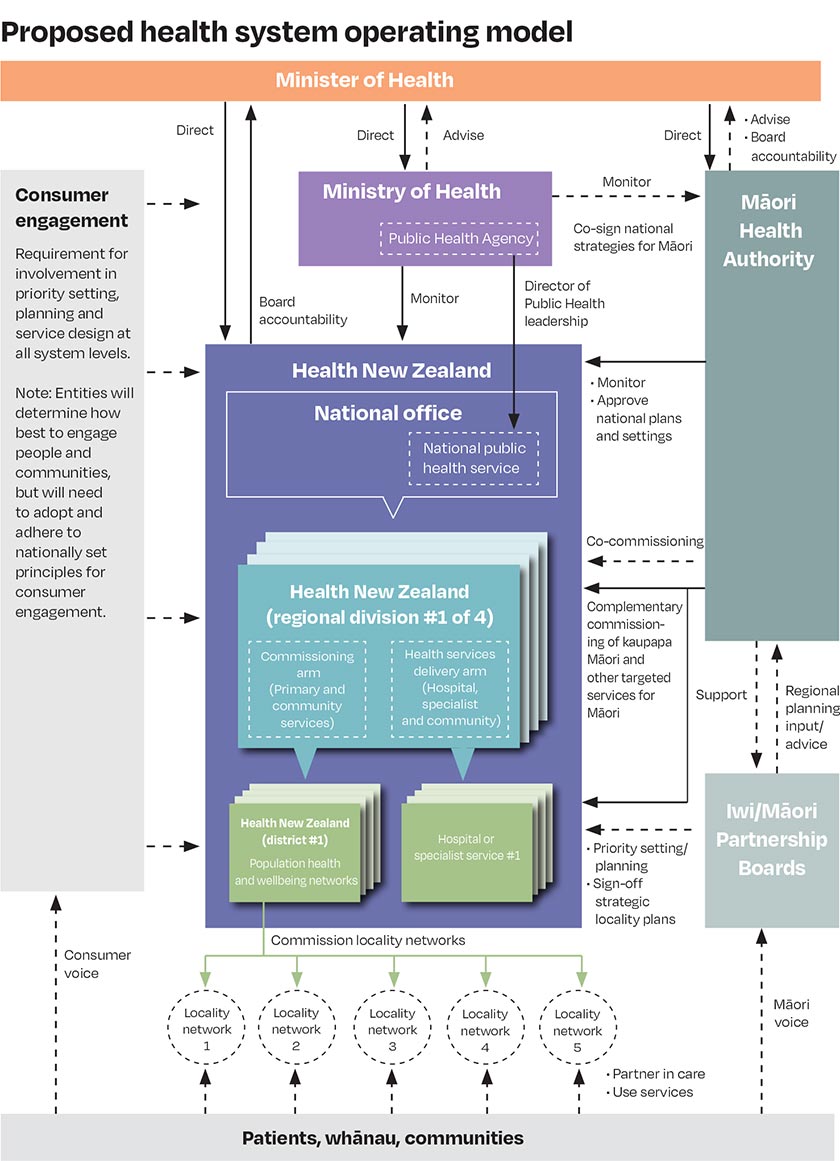

I have deliberately not gone through the new structure, instead focusing on its design principles. However the diagram provided says it all. At the top is the minister and Ministry of Health, power descending from the top. Patients do not appear.

My perspective is the other way up, with the patients at the top. I do not deny the necessity of central structures, especially given that the centre is the source of funding.

But I start with the people, and those treating and supporting them, and build the structure with their wellbeing at the centre of our vision – not the dollar.

Brian Easton, BSc(Hons), BA, FRSS, CStat, DSc, is an economist, social statistician, policy analyst and historian. He has held a variety of university teaching posts, and is a commentator and well-published author. He was formerly the director of the New Zealand Institute of Economic Research, and was economics columnist at the The Listener for 37 years. He has just published Not in Narrow Seas: The Economic History of Aotearoa New Zealand where some of the material in this article comes from.

This article – the final in a series of two – is an edited version of a speech given by the author at the conference of theatre managers and educators in Dunedin in May. It is used with permission.

The first article entitled “The roots of today’s public health system” is also available on this website.