The coalition Government has overturned legislation, gutted mechanisms and eliminated women’s involvement in decision-making about gender-based pay discrimination in Aotearoa New Zealand.

The changes, announced in the May 2025 Budget, are a matter of economic and political discrimination against women, which has resulted in significant injustice.

Her Caring Counts report had key role in Kristine Bartlett case

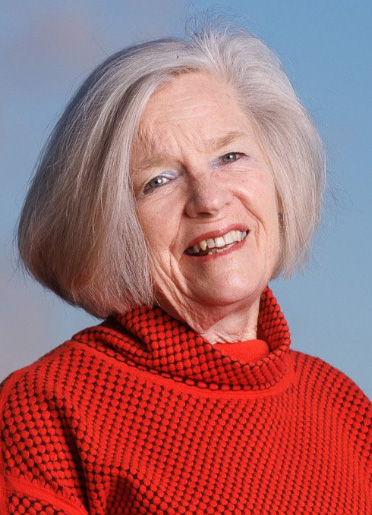

Dame Judy McGregor is a former newspaper editor and academic, was the first Equal Employment Opportunities Commissioner for the Human Rights Commission and chaired the Waitemata District Health Board through the COVID-19 pandemic.

Her Caring Counts report played a key role in promoting the Kristine Bartlett union-inspired case that achieved better pay for workers in the aged-care sector in 2017.

The report was based on the three weeks she spent undercover, experiencing first-hand what she branded as “slave labour”.

The Government had no political mandate for the changes, given that radical change to the pay equity regime was not contemplated in any party political manifesto at the last general election. The changes constitute the most significant regression of women’s economic and political rights in 35 years.

Changes occurred without consultation

The pay equity of 180,000 women, many low paid, involved in 33 claims which had been lodged and were undergoing due process, has been cancelled by this austerity legislation. The unheralded changes occurred without consultation with women and the public.

Over four years, $12.8 billion had been set aside in the Government’s accounts to remedy gender pay discrimination, funding which has now been diverted for other use.

In addition, women whose pay equity claims had been previously settled have now also been denied reviews for a decade. Employers’ powers have been significantly strengthened, including veto powers, to ensure that previously legitimate claims for pay equity will be considerably reduced and far fewer settlements, if any, will be implemented.

All of these arbitrary and discriminatory changes were made despite the Government in its most recent report to the United Nations Committee on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW) claiming practicality, utility and effectiveness for the law it has now overturned and the mechanisms and tools that it has now disbanded.

The changes constitute the most significant regression of women’s economic and political rights in 35 years.

Discrimination against women

The Equal Pay Amendment Act 2025 had the effect of substantially destroying the previous pay equity system. Prior to its elimination, 13 claims had been successfully settled, including a claim by 38,000 nurses employed by Te Whatu Ora — Health New Zealand.

This particular claim, like others that had been settled, contained a process requiring periodic reviews, which had to take place at least once every three years.

Thirty-three claims were in process when the 2025 legislation was passed. The new law means:

- All current unsettled claims were cancelled.

- All settled claims had their review clauses eliminated, whether they were in pay equity claims, collective agreements or individual employment contracts.

- Women involved in settled claims were prohibited from raising a new claim for 10 years

- Employers can decline to participate in a multi-employer claim.

- The concept of “arguability” in previous legislation as a gateway to raising a claim has been replaced by an employer or employers deciding whether the claim has “merit.” If employer(s) say “no”, claimants have no options other than to litigate or abandon their claims.

- Comparators have been curtailed by a mandatory narrowing. Comparators employed by the same employer must be used if they exist. If not, comparators employed by similar employers must be used. If there are none available in either class, comparators in the same industry or sector must be used.

- Employment lawyers say the new comparator provisions will magnify and perpetuate inequity.1 One of the biggest claims now defeated by the legislation is that of the 65,000 care and support workers who work in the community, in mental health and in aged care. Given the heavily female nature of this employment, there may be no available comparators under the austerity legislation. This in effect means that an inferior class of low-paid, female employee has been created.

- The denial of women’s rights is compounded by the retrospectivity of the legislation. Parliament’s Legislation Design and Advisory Committee (LDAC), which is available to help better lawmaking, has guidelines which state: “The starting point is that legislation should not have a retrospective effect. It should not interfere with accrued rights and duties” and “legislation should have prospective not retrospective effect”. The presumption against retrospective legislation which leads to uncertainty and injustice is contained in section 12 of the Legislation Act 2019.

- Significantly, many women in pay equity claims now have no domestic remedies available in the meantime because of the legislation. This means the act potentially breaches Article 2(3) (a) of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights which states: “Each State Party undertakes to ensure that any person whose rights or freedoms . . . are violated shall have an effective remedy, notwithstanding that the violation has been committed by persons acting in an official capacity.”

Denial of rights to participate in legal and policy decisions that directly affect them

- Lack of consultation

A new and significant feature of the Government’s regression on pay equity was the shutting out of women’s voices, involvement and agency in all aspect of the pay equity changes. This democratic deficit is damaging to public trust in legislative governance.

Participation in the formulation of government policy is specifically mentioned in CEDAW, Article 7. This obligates the Government to ensure to women on equal terms with men, that they enjoy the right to participate in policy formation. The Coalition Government is likely to claim that Article 7 does not apply in this case because men were not consulted either.

There was no prior consultation with the Ministry for Women, no external consultation with any major women’s civil society groups of NGOs or with individual experts with pay equity expertise. Trade unions which have been at the forefront of pay equity claims were not consulted either. This troubling lack of trust in stakeholders and disregard for tripartite industrial processes is a new dynamic in the political-policy nexus surrounding pay equity.

Since the 1972 Equal Pay Act, equal pay and pay equity progress has been characterised by task forces, reports, inquiries, legislative developments and varying degrees of political will. Despite often distinct political differences, pay equity development took place in an environment where women were able to access the process as workers and advisers. The new no-trust dynamic is especially damaging to effective policy development to advance women’s rights.

- Poor parliamentary processes and human rights implications

The disclosure report on the legislation indicated there was no regulatory impact statement to inform policy decisions on the Bill when it was introduced to Parliament. Those most directly affected, low-paid women, were also not considered in policy analysis nor was any analysis undertaken on whether the bill was consistent with the Treaty of Waitangi, due to “ministerial time constraints”.2

The general public, women’s groups and Opposition MPs were denied access to the advice given to Cabinet about the human rights implications of the Equal Pay Amendment Bill 2025 before it became law.

They were ‘alarmed that the human rights implications were not disclosed or examined and regarded as insignificant’.

When the cabinet paper was released, the traditional section on the human rights implications was redacted so it could not be read. It can be presumed the redacted section would have referenced the Government’s obligations under CEDAW Article 11(1)(d), “the right to equal remuneration, including benefits, and to equal treatment in respect of work of equal value as well as equality of treatment in the evaluation of the quality of work” and ILO Convention 100 relating to Equal Remuneration.

Four Equal Employment Opportunities (EEO) Commissioners (the current Commissioner and all three former commissioners) with the Human Rights Commission formally called on the Government to release the human rights analysis. They were “alarmed that the human rights implications were not disclosed or examined and regarded as insignificant”.3 No response was forthcoming.

The current EEO Commissioner, Gail Pacheco, made a subsequent request under the Official Information Act. The Government continues to withhold the human rights implications on the grounds of “professional legal privilege”. It is unprecedented for the human rights implications of bills not to be disclosed in this manner.

- Urgency and no select committee

Aotearoa New Zealand does not have a written constitution. Its human rights legislation consists of the Human Rights Act 1993 (HRA) and the New Zealand Bill of Rights Act 1990 (NZBORA). Neither are entrenched and cannot be used to strike down inconsistent legislation, although an amendment to the Human Rights Act allows complaints about discriminatory enactments.

Aotearoa New Zealand continues to be asked by various UN treaty committees to strengthen constitutional safeguards, to no avail. The brutal and radical changes to pay equity legislation are a contemporary example of the pitfalls of the unbridled power inherent in parliamentary sovereignty.

The use of urgency by successive governments has been criticised domestically by a raft of researchers, legal experts and Opposition politicians because of its negative impact on the quality and integrity of law-making.4 Its use is increasing rapidly and the Government is likely to set a record for speed on controversial law change,5 much of it dismantling workers’ protection and rights. The changes to workers’ protections are driven by the ACT Party, which has an unashamed ideological affection for the concept of “the market rules”.

The new no-trust dynamic is especially damaging to effective policy development to advance women’s rights.

If a bill is introduced under urgency, this foreshortens democratic deliberation. Urgency closes off formal avenues for public feedback through a select committee, which is a unique feature of Aotearoa New Zealand’s law-making process.

The Equal Pay Amendment Act 2025 was passed under urgency being announced on a Tuesday morning, introduced into Parliament a few hours later and passed by Wednesday evening. No select committee examination took place.

Government rationale

Why has the Government undertaken such a policy change? The answer is partly ideological and mostly financial — about resources and priorities. ACT leader David Seymour categorically told the media that axing pay equity settlements had “saved” the Government’s 2025 Budget.

The estimated reductions allowed Finance Minister Nicola Willis to reallocate $12.8 billion in savings, previously reserved to pay for gender discrimination in employment. As Public Service Minister, she abolished a specialist pay equity unit within the Public Service Commission to assist unions and employers with pay equity claims, also without consultation.

Government ministers pay muted rhetorical homage to what they call “sex-based discrimination”. But paying for gender-based pay discrimination has been sacrificed for other political priorities.

Why has the Government undertaken such a policy change? The answer is partly ideological and mostly financial — about resources and priorities.

New Zealand did not lack the resources to settle legitimate claims. It had the $12.8 billion earmarked for pay equity, but chose to take money owed to under-valued women to balance its books.

The UN committee monitoring the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights states:

“ A failure to remove differential treatment on the basis of a lack of available funds is not an objective and reasonable justification unless every effort has been made to use all resources that are at a State party’s disposition in an effort to address and eliminate the discrimination as a matter of priority.”6

Previously a poster child for equality

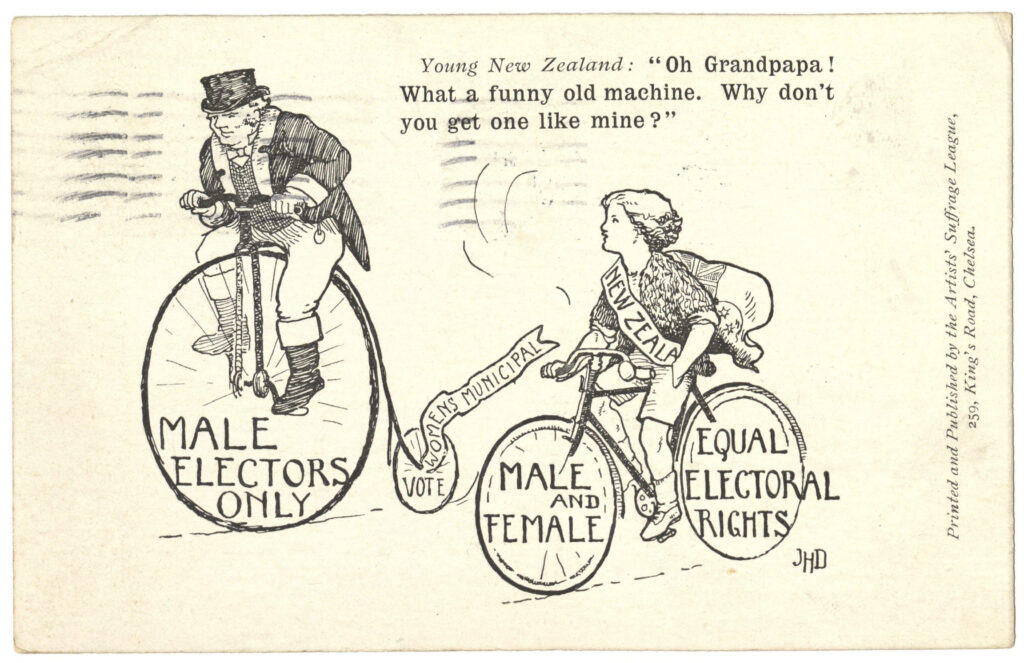

Aotearoa New Zealand has previously been regarded internationally as a poster child for gender equality. However, this Government has fundamentally and deliberately backtracked on pay equity. Women feel angry at the disrespect shown to them by a policy change made about them, without them. They are despairing of the halt to pay equity progress given Aotearoa New Zealand was the first nation state to grant women’s suffrage.

The Pay Equity Coalition Aotearoa (PECA) has formally advised the UN Committee on the Status of Women of these fundamental breaches of the political, economic and social rights of women in this country.

It has also requested that a committee member visit this country to hear the stories and witness personally the anger and despair of thousands of women, many of them Māori, Pacific and migrant women workers, who are now condemned to decades, if not a lifetime of poverty wages.

See also: ‘We won’t back down’ — NZNO pushing ahead with 12 pay equity claims

This article is an edited version of a submission, written by Judy McGregor, from the Pay Equity Coalition Aotearoa (PECA) to the United Nations Committee on the Status of Women on gender pay discrimination in Aotearoa New Zealand. PECA is a national coalition of unions representing women workers in the care and support, health, education sectors, and in the public service, and women’s civil society organisations.

- Of the 33 existing pay equity claims which were cancelled, 12 were from NZNO or NZNO with other unions.

References

- Public Service Association. (2025). Equal Pay Amendments Explainer with Peter Cranney. (Youtube video).

- Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment. (2025). Departmental Disclosure Statement: Equal Pay Amendment Bill 2025.

- Te Kāhui Tika Tangata — Human Rights Commission. (2025, May 9). Current and former Commissioners call for the release of equal pay amendments’ human rights analysis.

- Geiringer, C.,Highee, P., & McLeay, E. (2011). What’s the hurry? Urgency in the New Zealand Legislative Process 1987-2010. Victoria University Press with the New Zealand Law Foundation.

- Smith, P. (2024, March 3). Parliament: Why so much urgency? RNZ.co.nz.

- UN Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights. (2009). General comment No. 20: Non-discrimination in economic, social and cultural rights (art. 2, para. 2, of the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights).