Saju Cherian was six months into his nursing degree when his first wife of seven years, Shanty – a nurse – died suddenly.

“She was fit and healthy and one day she didn’t wake up.”

A coronial investigation could not determine the cause of death and found it to be “unexplained”, about a year after Shanty’s death.

Following a complaint by Cherian, the coroner referred the case to medical researchers who eventually found Shanty had a rare hereditary heart condition, Brugada syndrome, and it was likely she died from a heart attack.

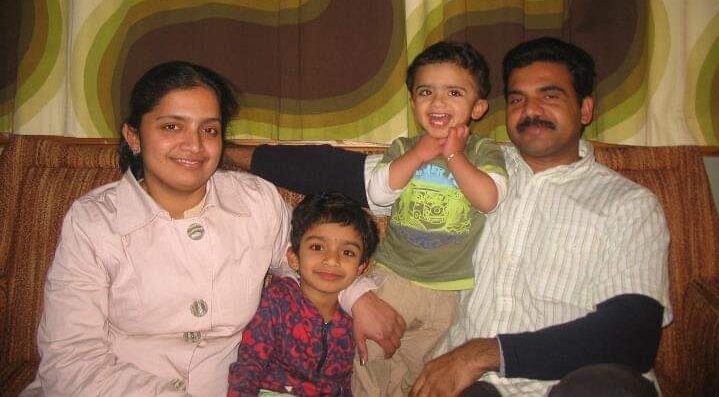

The mental health nurse and new board member says his wife’s drive to gain her nursing registration and complete a bridging programme in New Zealand was the catalyst for the couple’s move from Kerala, India a few years earlier.

Now remarried and celebrating the arrival of a new baby, the past trauma of losing Shanty has become a little easier to cope with, Cherian said.

When he first arrived in New Zealand, Cherian struggled to find work with his masters of economics and, inspired by his wife’s career, started a bachelor’s degree in nursing.

“She shared some stories from work and I thought that sounds good, helping people to get well.”

But after her death Cherian found himself alone without family support to care for the couple’s two young children.

“My wife wanted to do this and she wanted our children to grow up here.”

He says the small Palmerston North Kerala community came to his aid, helping to raise thousands of dollars needed to take his wife’s body home for burial.

Back in India, Cherian said he was under pressure from his family to stay there, where he and the children would have support, but he wanted to honour his wife’s vision to live in New Zealand.

Starting again

At first he returned to Palmerson North on his own, but unable to bear the separation from his children, they joined him a few months later.

“It was a tough struggle looking after the children, studying and working part-time.”

Immigration rules at the time meant he wasn’t eligible for government financial assistance until two years after being granted residency.

With the support of the Palmerston North Kerala community, he was able to pay for his student fees for the next 18 months. And in the third year he was able to take out a student loan.

For the past seven years he has worked in an acute mental health unit in Palmerston North Hospital, and is now an associate charge nurse manager.

“I liked being able to spend time with patients – other areas are very task-orientated.”

Becoming an advocate

Cherian’s involvement with the Kerala and other migrant communities became entwined with nursing and his support of NZNO, he said.

A majority of people in the Palmerston North Kerala Association and the Kerala Catholic Community – groups Cherian helped found – were nurses as the Indian state was the first to offer nursing education in India.

Cherian joined NZNO as a new graduate and could see it had the power to improve pay and conditions for nurses. But more recently he realised many migrant nurses were reluctant to get involved.

“When it comes to the union, it can feel like they are questioning authority, or going against the authority.”

Many migrant nurses were used to working in a more authoritarian work culture where employee rights and unions were either non-existent or weak, he said.

While NZNO has began negotiating for better pay and conditions for members since 1969, in Kerala the first nurses union was established in 2011, following the suicide of a young nurse.

“When it comes to the union, it can feel like they are questioning authority, or going against the authority.”

Indian nurses who came to New Zealand faced many hurdles to gain registration and residency, and were reluctant to risk losing their hard-fought gains.

Cherian said he was encouraged to become an NZNO delegate and run for a position on the board by fellow migrant nurses, to increase membership among this group and advocate for them.

He said New Zealand needed to increase its own nursing workforce but internationally qualified nurses (IQN) would still play an important role in the shorter term and they needed to be treated fairly.

Cherian’s second wife, Nitha, a health care assistant and also from Kerala, is considering studying nursing in the future, when immigration rules allow.