It might not seem the most glamorous of roles but we stomal nurses love our job! It’s an amazing role, because we stay with someone their whole journey — from diagnosis, through surgery to living in the community, and until patients get the stoma reversed or pass away.

So we get to form relationships with patients that nurses don’t get to do so much on the ward.

I originally wanted to be a cardiac nurse. But when I came home from Australia to Hawke’s Bay in my early 30s, colorectal was the only ward hiring. Then I started having babies, so I wasn’t going anywhere and ended up staying there for 12 years before moving into a new stomal nursing role in another department.

Every day we see the impact of our work, which is very satisfying.

It’s so noticeable to the patient and to us how much of a difference we make in people’s lives. If anything goes wrong with a stoma, it’s not life or death, but it’s extremely embarrassing and extremely uncomfortable – and just traumatising. People don’t want to have accidents in public.

And patients really appreciate us. So all stomal nurses love their jobs – they really do. If you don’t love it, you just couldn’t do it — you have to be committed and passionate.

Who are stoma patients?

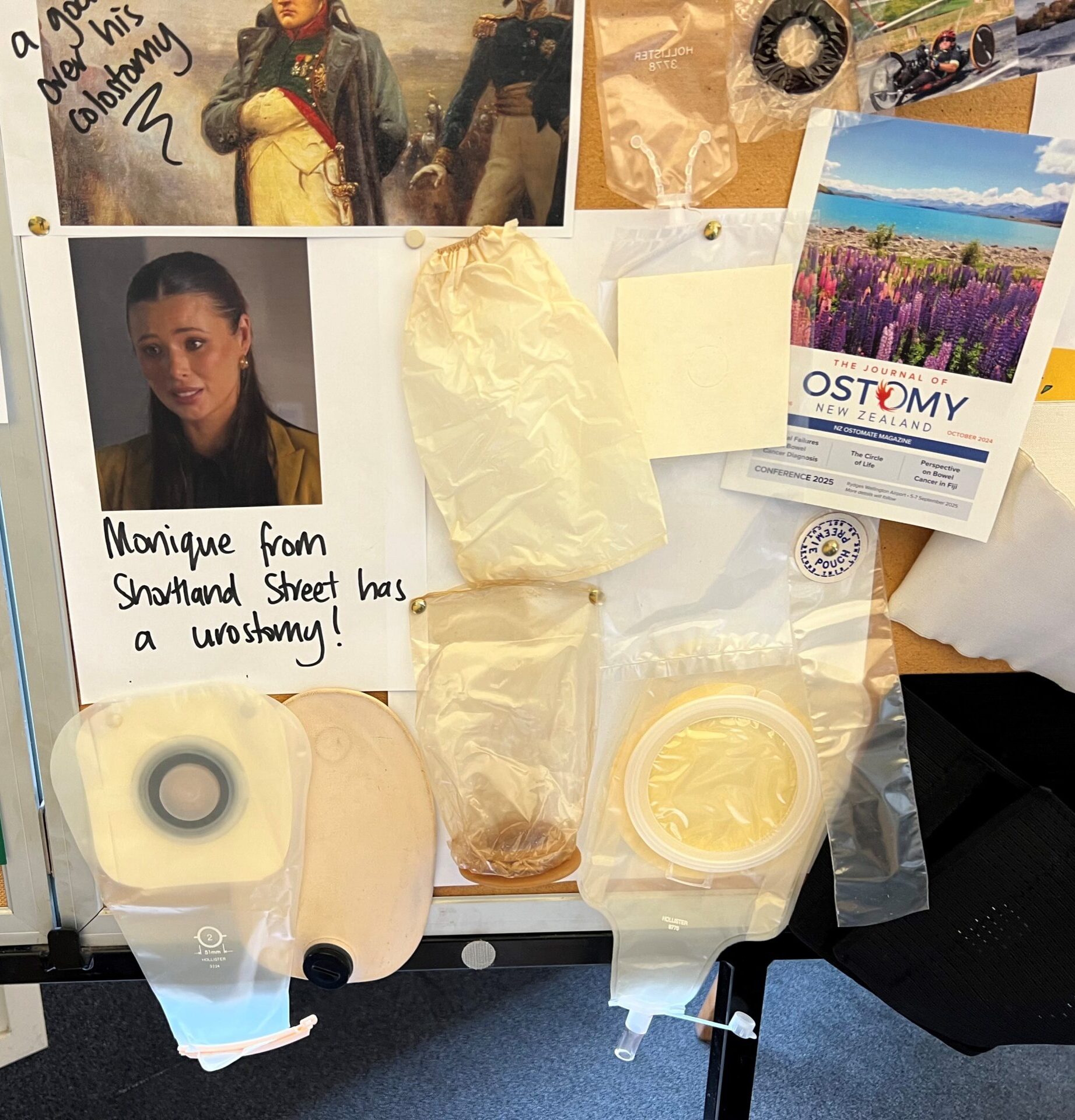

Most of our patients are cancer-related — and it’s mostly rectal. Often parts of their rectum have been removed and rejoined. That usually requires a temporary ileostomy — a stoma (opening) from the small intestine with a pouch. Other kinds of stomas include colostomy (a large intestine stoma), and ileal conduit after removal of the bladder due to cancer.

If surgeons are worried about the join holding, then they make a stoma upstream to divert the faecal flow so that you can allow that join to heal. That’s a faecal diversion.

Other stoma patients include the elderly, frail, immuno-suppressed, smokers and diabetics.

It’s not as easy as slapping a pouch on – I think that’s what a lot of people think you do. Whack on a pouch and send people on their way.

Some have inflammatory bowel conditions like Crohn’s disease or ulcerative colitis,

It’s not as easy as slapping a pouch on – I think that’s what a lot of people think you do. Whack on a pouch and send people on their way. But so much of our role is psychological.

There is a lot of counselling. People are so freaked out — it’s horrific for them. Some people welcome their stoma, as it’s a relief of their symptoms. But for a lot of people, they’re dealing with their cancer diagnosis, treatment and a stoma — they’ve got a shit bag on their tummy.

It affects every facet of your life. You don’t want to go out to the supermarket if you think you’re going to smell like shit, you’re worried about leaks, your sex life goes out the window. Everything — it’s your whole body image.

But usually by the end of it, most patients say that the stoma was the least of their problems.

Most stomas are temporary these days, so we see them pre-op, we see them in the hospital, get them prepared to go out in the community – and that’s probably our most intensive time, that first four to six weeks, when they’re getting their new stoma.

Education is also a major part of our role. We prepare patients for their surgery, explain what to expect — demonstrate the pouch, explain what will happen afterwards and then mark their abdomen where it is best to place the stoma.

After surgery, we check in, make sure they’re getting the hang of it, that they’re having no leaks, that their skin is okay, that they’re getting out and about doing their thing. Once they hit six weeks, they usually are pretty much independent and confident, and off doing their own things.

But it’s not always just at the start. Sometimes, people can have a stoma for years — decades — and then start having problems and complications after 40 years.

Others get theirs reversed after the six-week minimum — if they are fit or get prioritised.

Tiny workforce

We stomal nurses are a tiny and highly-specialised workforce of around 60 or so in New Zealand. The college has 180 members — but that includes hospital, primary health and district nurses who regularly work with stoma patients.

Getting qualified isn’t easy either. There hasn’t been a stomal specialty nursing course in New Zealand since 2001. There are two options, both in Australia and both one-year part-time post-graduate. One is at Curtin University in Perth and the other is through the Australian College of Nursing.

So the stoma nurses are getting big messes in the community because patients get discharged in a bad state.

Studying in Australia is just unaffordable for most nurses — the Curtin University qualification costs A$13,500 and you need to spend two weeks in Perth for the clinical practice, which is cost-prohibitive in itself.

Former college chair Emma Ludlow is negotiating for Curtin University staff to come over to New Zealand each year to supervise the clinical part of that course in Auckland. We need at least 15 participants for that to go ahead — and it looks like we might have enough.

More details on that can be found here, for those who are interested.

Other stomal nurses, like me, haven’t done any formal training but have just learned on the job over many years. Although I did focus on stomal nursing while studying for my Masters in nursing at the University of Auckland — my thesis was on hydration and people with ileostomies (where the stoma attaches to the small intestine, rather than the large intestine, as with a colostomy).

Cutbacks?

We work across hospitals, communities and aged-care — we go where our stoma patients are. But some regions have cut back, such as Auckland. Previously, their stomal nurses would move between the community and hospital but over the past year or so they have been replaced in Auckland hospitals by ward nurses.

Te Whatu Ora Auckland–Te Toka Tumai don’t seem to want to pay for specialists, so they think a nurse on the ward can do what a stoma nurse does. And I can tell you right now that they can’t.

So the stoma nurses are getting big messes in the community because patients get discharged in a bad state — then they have to travel across Auckland from one patient to another. It’s pretty dire — it’s not great.

But here in Hawke’s Bay, and most other regions, we stoma nurses can go anywhere the patient is.

On the college horizon

Our main focus at the moment is our upcoming biennial conference Resilience in Christchurch on March 5 and 6, 2026.

Alongside the Australian association of stomal therapy nurses (AASTN), we are also helping prepare for the the Asia-Pacific Federation of Coloproctology congress in Sydney in 2027.

We have a strong relationship with our brothers and sisters at AASTN and celebrated stomal therapy week together back in June. We also share a stomal nurse training scholarship with them for both Australian and New Zealand stomal therapy nurses.