Tēnā koutou, tēnā koutou, tēnā koutou

Ko Aoraki te māunga

Ko Waitaki te awa

Ko Murihiku te marae

Ko Wharetutu rāua ko Tahu Pōtiki ngā tipuna

Ko Takitimu te waka

Ko Ngāi Tahu, ko Kāti Māmoe ngā iwi

Ko Wilson te whānau

Ko Maryann Wilson taku ingoa

Nō reira, tēnā koutou, tēnā koutou, tēnā tātau katoa

E hara taku toa i te toa takitahi,

engari he toa takitini

My strength is not from myself alone,

but from the strength of the group.

For Māori and other indigenous people of the world, natural disasters, unusual weather events and the arrival of COVID-19 have magnified health inequities and longstanding negative health outcomes, as well as disturbing their usual way of life.

Government pandemic strategies originally aimed to stop the spread of the COVID-19 virus, primarily by vaccinating Aotearoa’s Māori and non-Māori populations and use of lockdown measures. These lockdown measures aimed to reduce the movement of populations in order to limit the virus’s access to its main vehicle of respiratory transmission — people.

However, for many people, lockdown measures undermined their ability to access essential health determinants such as education, employment, income, housing, and connection with whānau and other support systems, including cultural.

Opportunities in a crisis

As can happen in crises, however, opportunities also presented themselves.

While the COVID-19 pandemic highlighted how stretched and fragile health-care services in this country are, it also demonstrated the value of nurses and health professionals as frontline essential workers caring for, and collaborating with, tāngata whai ora (people seeking health) who were affected by the virus.

It is within this context that Māori wānangatanga (knowledge) and whanaungatanga (relationships between people, things and the environment) and Māori health nursing gained significance.

Crises such as the pandemic can encourage the use of Māori health nursing skills because emergencies force us to work together, encouraging kotahitanga (unity).

At the same time, the usual health-care structural constraints are loosened, freeing nurses and other health professionals to exercise the human values of warmth, kindness and fellowship, which are made explicit in te ao Māori.

During the pandemic, this country was also experiencing a rapid increase in the use of te reo Māori and Māori knowledge.

This was particularly evident in the news media, but also in crown entities such as educational and health-care organisations, which have a significant role in ensuring te Tiriti o Waitangi principles are embedded in the structure and delivery of education and health care.

Health service crises such as the pandemic can encourage the use of Māori health nursing skills because emergencies force us to work together, encouraging kotahitanga (unity).

This growth in the use of te reo and Māori knowledge during the pandemic could be partly seen as coincidence, partly the ongoing process of revitalising te reo and a way of connecting with Māori during the lockdown.

Before the pandemic, the Crown’s health and social services were expected to engage in a meaningful way and demonstrate a consistent cultural approach when working with Māori2.

During the pandemic, nurses and other health professionals were able to gain skills and demonstrate their knowledge through the use of te reo, engaging with tikanga practices and being aware of te ao Māori in their mahi.

Using this cultural approach to providing care can potentially help reduce Māori health inequities and improve health outcomes.

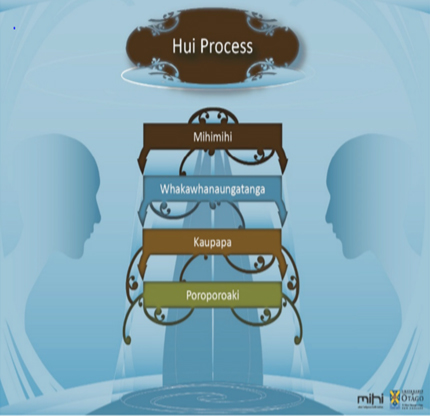

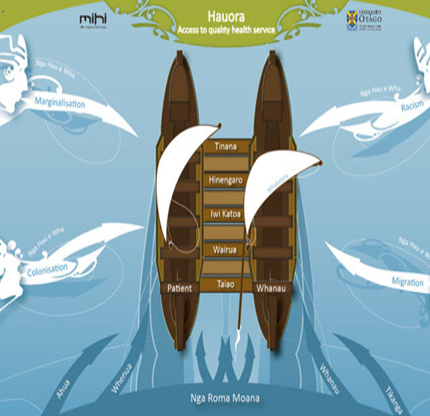

The indigenous health framework3 (see diagram below), comprising the hui process4 and the Meihana model (a clinical assessment framework)5, are cultural approaches which can expand nurses’ ability to improve health care for Māori and their whānau5.

Presentation in Australia

At the 19th National Nurse Education Conference held on the Gold Coast, Australia, in June last year, I gave a presentation on the development of the Waitaha (Canterbury) graduate certificate in Māori health nursing.

I explained to an appreciative audience of both nursing educators and clinicians that the development of this course, which started in 2016, was a collaboration between Te Whatu Ora in Canterbury and the Ara Institute of Canterbury.

Underpinned by te ao Māori, te reo, tikanga practice, Māori beliefs and values and the indigenous health framework3,4,5, the Māori health nursing course goes some way to strengthening and advancing cultural capabilities within the nursing workforce.

The key learning outcome of this course is for nurses to be able to critically analyse and discuss the contributing factors that affect the health of Māori, with the aim of improving their health status.6

How the course was developed

Ada Campbell and myself, Maryann Wilson — senior nursing lecturers in the department of health practice at Ara Institute of Canterbury — were reviewing the content and structure of the Wanaka Hauora (Māori health) course in Ara’s undergraduate bachelor of nursing programme.

At around the same time, at Te Whatu Ora Waitaha, postgraduate education nurse coordinator Jo Greenlees-Rae and her nursing workforce development team were reviewing aspects of their nursing education programmes. These included their nursing entry to practice (NETP) programme and professional development recognition programme (PDRP).

During our collegial discussions with the Te Whatu Ora team, it became apparent that while staff from both organisations were responsible for developing the same nursing workforce, they had different approaches to teaching te Tiriti o Waitangi and different learning objectives in these programmes.

We agreed that it was important to engage and collaborate in the development of Māori health nursing.

Yet these undergraduate students and registered and enrolled nurses were working together in health care. We agreed that it was important to develop a consistent approach to Māori health nursing, rather than just developing a pipeline of nurses for the Waitaha region. Hence the graduate course on Māori health nursing was jointly developed.

Course participants tend to come from a broad range of nursing backgrounds, including occupational health, primary health, mental health, Māori health providers, and surgical and medical units.

Positive feedback

Participant and stakeholder feedback has been positive. For example, one participant reported their pre-course expectations as being: “I thought I would learn about health statistics, Māori models of health, cultural safety, and te Tiriti o Waitangi . . . and I did, but I learnt so much more.

“On reflection, I realised people I knew and cared for had become health statistics and that they were reflective of the health disparities which currently exist in New Zealand.”

Participant feedback has enabled the graduate course to be expanded to include both online and kanohi ki te kanohi/face-to-face delivery. While the original participants were from the Waitaha region, participants are now from all over New Zealand.

Successful graduates also return to share how their practice has changed since completing the course, and contribute to the course’s kaupapa.

However, the application of this new knowledge requires a development process that involves time and long-term commitment.

Participating in Māori health education enables nurses to gain cultural competence, knowledge, values and skills, with the aim of improving the experience of Māori engaging with health-care services.

However, the application of this new knowledge requires a development process that involves time and long-term commitment. Once applied, nursing practice can be strengthened and be effective across different Māori health contexts.

Course participants are required to produce a 2000-word case study. This requires them to analyse health disparities due to colonisation, racism, migration, and marginalisation on Māori. They then apply the indigenous health framework3, 4, 5, and cultural safety and te Tiriti o Waitangi principles7 to the case study.

Analysing the health experiences of Māori to whom they have provided care, enables nurses to strengthen their practice to better meet Māori health needs.

Since the course started in 2016, it has been delivered annually by Te Whatu Ora staff, and eight cohorts have graduated, a total of around 100 nurses. It includes two days in class in Christchurch, hearing presentations from Māori nursing leaders from across the Waitaha health sector.

Feedback from participants last year lead to the course’s name being changed to “graduate course in te Tiriti o Waitangi and Māori health nursing”.

Observing the stressors on nursing staff

As part of ongoing professional development, I spent time in clinical practice during the pandemic. This allowed me to witness the stressors of the clinical environment in the lead-up to Christmas. It also allowed me to witness and participate in the use of Māori health nursing skills in an understaffed unit.

One particular stressor was the movement of nurses between units to fill nursing shortages. In the unit I was working in, one nurse was moved away and not replaced for a shift — the remaining staff still had duty of care for tāngata whai ora in their unit, which was at capacity.

The removal of one nurse highlighted how equity of care for tāngata whai ora could be compromised. In our unit, this impaired our ability to conduct a successful admission process, so our efforts to connect and engage with tāngata whai ora and provide effective nursing care became vulnerable.

Yet the day flowed — we all worked together: RNs and ENs updated computer information and tag-teamed with clinical data — of who was doing what, where and when. And lunch was taken on the run.

Using elements of te ao Māori

As I mentioned earlier, it is within crisis events that opportunities present themselves and on this day they did. Elements of te ao Māori/the Māori world and te Tiriti o Waitangi principles were demonstrated by the nursing staff.

These ranged from answering the ward telephone in te reo — “Kia ora, welcome to…” — to demonstrating whanaungatanga with tāngata whai ora at the beginning of their admission process, and empowering them to establish whakamanatanga, ie make connections between previous and new health experiences.

For tāngata whai ora, this kind of nursing practice helps them to establish tino rangatiratanga/self-determination for their care and future life meaning — a key aspect of their recovery journey.

This involves practising in the moment, and viewing the care they provide through the lens of te ao Māori.

I am aware that crisis events and their protracted impacts, as well as adjusting to the daily changes and expectations of the current health environment, are stressful. Such stresses are now considered by many as the new normal for both nursing staff and tāngata whai ora.

However, even in stressed circumstances, nurses can practise the art of nursing from another, different perspective. This involves practising in the moment, and viewing the care they provide through the lens of te ao Māori; it involves incorporating Māori models of health such as te whare tapa whā8, the hui process4, and the Meihana model5, and undertaking reflective practice.

This entails nurses moving their perspective from what care they should be providing, given appropriate resources, to what cultural care they are effectively providing at this moment in time, for this tāngata whai ora and whānau.

Collective kotahitanga

This creates an environment of collective kotahitanga/unity.

In the example from clinical practice mentioned earlier, the removal of one nurse for a shift enabled those nurses remaining in the unit to join with tāngata whai ora and practise with a Māori cultural perspective.

On this occasion, the environment of collective kotahitanga enabled the nurses to buffer the stressors of the clinical environment, and show the strength of their cultural capability and Māori health nursing practice.

So, in those often self-defining crisis moments of nursing, “be brave, be bold”, and be that culturally capable nurse who can achieve positive health gains for Māori.

Maryann Wilson (Ngāi Tahu, Kāti Māmoe), RN, MN, PGDipHSci (mental health), GradDipTertTchgLn, is a senior academic nursing lecturer and kaiāwhina Māori ākonga support for Tihi-o-maru/Timaru, at Te Pūkenga — Ara Institute of Canterbury, Ōtautahi/ Christchurch.

Acknowledgements: The author acknowledges the support and assistance of Ada Campbell, RN, CertAT, DTT, MHealSc, an academic nursing lecturer at Te Pūkenga — Ara Institute of Canterbury, Ōtautahi/ Christchurch; Jo Greenlees-Rae, RN, BN, MN, Cert AEd, postgraduate education nurse coordinator/kairuruku nehi, nursing workforce development, Te Whatu Ora/Health New Zealand Waitaha/Canterbury.

References

- Stewart, G. T. (2021). Māori philosophy: Indigenous thinking from Aotearoa. Bloomsbury Academic.

- Mclachlan, A. D., Pitama, S., & Adamson, S. J. (2020). Kia whakatōmuri te haere whakamua: Engaging Māori rural communities in health and social service care. AlterNative: an International Journal of Indigenous Peoples, 16(3).

- Al-Busaidi, I. S., Huria, T., Pitama, S., & Lacey, C. (2018). Māori Indigenous Health Framework in action: addressing ethnic disparities in healthcare. New Zealand Medical Journal, 131(1470), 89-93.

- Lacey, C., Huria, T., Beckert, L,. Gilles, M., & Pitama, S. (2011). The Hui Process: A framework to enhance the doctor-patient relationship with Māori. New Zealand Medical Journal, 124(1347), 72-78.

- Pitama, S., Huria, T., & Lacey, C. (2014). Improving Māori health through clinical assessment: Waikare o te Waka o Meihana. New Zealand Medical Journal, 127(1393), 107-119.

- Ara Institute of Canterbury. (2023). Graduate certificate in nursing: Māori health nursing.GCMH701/ENMH501 Course information booklet.

- Nursing Council of New Zealand. (2011). Guidelines for Cultural Safety, the Treaty of Waitangi and Māori health in nursing education and practice.

- Durie, M. (1998). Tirohanga Māori: Māori health perspectives. In Whaiora: Maori health development (2nd ed., pp. 66-80). Oxford University Press.

- Pitama, S., Robertson, P., Cram, F., Gillies, M., Huria, T., & Dallas-Katoa, W. (2007). Meihana model: a clinical assessment framework. New Zealand Journal of Psychology, 36(3), 118-124.