This article focuses on the Talking about Health: Long Term Conditions study1 participants’ experiences of general practice consultations.

The aims are to explore:

- Which doctors and nurses in the general practice team (GPT) are involved in their long-term condition (LTC) care.

- How people rated their experiences with the doctors and nurses working as part of the GPT.

- How people rated the overall LTC care and support received from the GPT.

- The relationship between ratings of general practice experiences and GPT support and their self-rated health and wellbeing.

- Whether people feel they know more about their health and make better choices when they have seen a doctor or nurse at their general practice.

- What people would like to change about their general practice consultations.

Most of the analyses are based on the 2016 (year 1) data, but the question regarding changes to consultations was asked in year 3, so the final aim is addressed using the 2018 data.

Specialist LTC nurses

In the MidCentral region, specialist community-based nurses are employed by practices or by the primary health organisation (THINK Hauora) to work alongside general practice teams in providing support for people with long-term conditions. They are known as community clinical nurses for long-term conditions (CCN-LTCs).

Measurement

To find out which primary-care practitioners were involved in our participants’ care, we provided a list comprising general practitioner (GP), practice nurse (PN), community clinical nurse for long-term conditions (CCN-LTC) and specialist nurse or nurse practitioner (SN/NP). Participants were asked to tick all that they had seen during the last year. Consultation experiences were rated separately for GPs and nurses (if they saw more than one, they were asked to rate the one seen most often), using the same set of 14 questions based on the New Zealand version of the United Kingdom General Practice Assessment Questionnaire2 for each.

The question stem was: “When you see the doctor/nurse at your general practice, how good are they at…” Each item represented a different aspect of the consultation, such as “listening to what you have to say” and “spending enough time with you”, and was rated using a six-point scale ranging from “very poor” (1) to “excellent” (6). Overall support received from the GPT for management of LTCs was rated on an 11-point scale from 0 (“not at all good”) to 10 (“extremely good”). Two statements were provided to assess whether people felt they had benefitted from their GPT consultations: “When I have seen a doctor or a nurse at my general practice, I feel I know more about my health”; and “When I have seen a doctor or a nurse at my general practice, I feel I can make better choices”. These statements were accompanied by the responses “strongly disagree” (coded as 1), “disagree” (2), “agree” (3) and “strongly agree” (4). General health (GH: single item with poor/fair/good/very good/excellent response options), physical health (PH: four-item scale) and mental health (MH: four-item scale) were measured using the PROMIS Global SF.3 The effect of LTC/s on quality of life was measured with a single question rated on a scale from 0 (“no effect”) to 10 (“very large effect”).

Results

The doctors and nurses involved in LTC care

Participants were asked about which doctors and nurses at their general practice had been involved in their LTC care during the last year (N=554). Almost all (96.8 per cent) had seen a GP and most (72.9 per cent) had seen a PN. A CCN-LTC had been seen by 29.6 per cent and an SN or NP by 29.1 per cent. Eighty nine people (16.1 per cent) said they had seen only one type of practitioner at their general practice during the last year; 72 (13.0 per cent) had seen just a GP, eight (1.4 per cent) an SN or NP, five (0.9 per cent) a PN and four (0.7 per cent) a CCN-LTC. The majority of participants had seen at least two practitioners, the most common combination being GP and PN (40.1 per cent).

Ratings of experiences with doctors and nurses

Table 1 displays the top and bottom-scoring items, based on mean ratings of GPs. It also shows the percentage of participants rating each as excellent or very good and poor or very poor.

Table 1. Top and bottom scoring items, based on mean ratings of GPs

| When you see the DOCTOR at your general practice, how good are they at… | Mean | Excellent or very good (%) | Poor or very poor (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| TOP | |||

| Making you feel comfortable about your physical examination | 4.9 | 67.1 | 2.0 |

| Knowing about your medical history and current treatment | 4.9 | 67.7 | 3.4 |

| Introducing themselves and asking you to introduce yourself | 4.8 | 66.9 | 4.7 |

| Listening to what you have to say | 4.8 | 65.2 | 4.0 |

| Explaining your problems or any treatment you need in a way you can understand | 4.8 | 65.4 | 3.9 |

| BOTTOM | |||

| Spending enough time with you | 4.5 | 56.0 | 6.7 |

| Involving family/whānau/fanau in decisions about your care | 4.5 | 55.4 | 11.6 |

| Knowing about you as a person, not just a patient | 4.4 | 53.2 | 10.7 |

| Learning about and helping with your social support needs | 4.2 | 44.7 | 12.4 |

The same results, but this time in relation to nurses seen in general practice, are presented in Table 2.

Table 2. Top and bottom scoring items, based on mean ratings of nurses

| When you see the NURSE at your general practice, how good are they at… | Mean | Excellent or very good (%) | Poor or very poor (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| TOP | |||

| Making you feel comfortable about your physical examination | 4.9 | 69.6 | 1.5 |

| Listening to what you have to say | 4.9 | 69.1 | 1.3 |

| Asking fully about your symptoms and how you are feeling | 4.9 | 68.0 | 1.9 |

| Introducing themselves and asking you to introduce yourself | 4.9 | 68.5 | 2.7 |

| BOTTOM | |||

| Involving family/whānau/fanau in decisions about your care | 4.5 | 58.1 | 9.4 |

| Knowing about you as a person, not just a patient | 4.5 | 55.5 | 8.7 |

| Learning about and helping with your social support needs | 4.4 | 51.2 | 9.2 |

There are obvious similarities in the top and bottom items for doctors and nurses, with making people feel comfortable during physical examinations and listening to people featuring in the top for both GPs and nurses. Knowing the patient, embracing an holistic view of health, and cultural needs being met were all rated relatively low for both disciplines. However, the observation that “asking fully about symptoms” appears in the top three for nurses, not doctors, and “spending enough time” appears in the bottom three for doctors, but not nurses, may reflect appointment systems enabling nurses to spend more time with patients than doctors, thus encouraging more in-depth discussion of issues. Interestingly, involving family/whānau/fanau in care decisions was considered to be “not applicable” by more than half of the participants.

GP experience (GPE) and nurse experience (NE) scales were formed by averaging the item scores. If participants had answered 12 or more of the 14 questions, they were included; if not, they were discarded from the calculation. GPE scores ranged from 1.4 to 6, with an overall mean of 4.7, and NE scores ranged from 1 to 6, with a mean of 4.8. Nearly half the sample rated their interactions with general practitioners and nurses at the general practice as very good to excellent on average. However a quarter of the respondents rated their interactions with their GP, and a fifth rated their interactions with nurses, as less than good (ie very poor, poor or fair).

Ratings of care and support for LTC management from the GPT

The overall ratings of care and support for managing LTCs received from doctors and nurses at the general practice (N=542) ranged from 0 to 10, with a mean of 7.9, a median of 8 and a mode of 9. Half of the participants rated the LTC support they receive to be a 9, or a 10 out of 10, and 14.2 per cent rated it as 5 or less.

Relationships between general practice experience and support and self-rated health and well-being

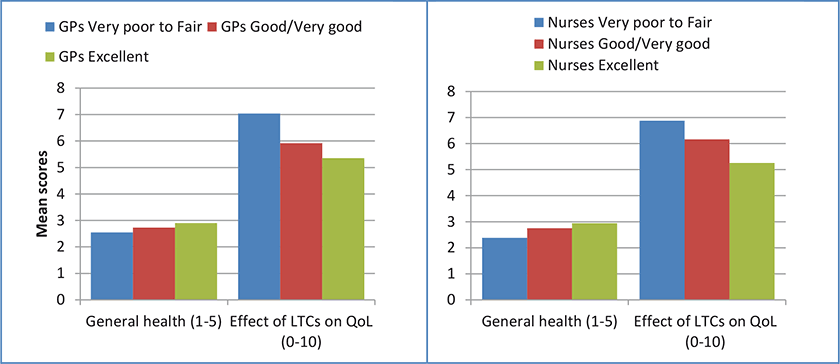

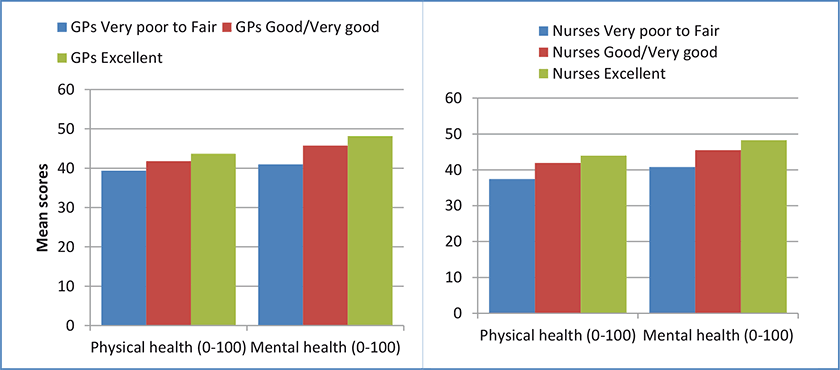

The mean GP experience (GPE) and nurse experience (NE) scores were re-coded into three groups, based on the following scores (category labels): 1 to 2.9 (very poor/poor/fair); 3 to 4.9 (good/very good); and 5 to 6 (excellent). Mean scores on general health, physical health, mental health and the effect of LTCs on quality of life were calculated and compared for the three groups. As can be seen in Figures 2 and 3, on average as the ratings of doctor and nurse experiences increased, so did ratings of general, physical and mental health. Higher general practice experience scores were also associated with LTCs having less of an impact on quality of life.

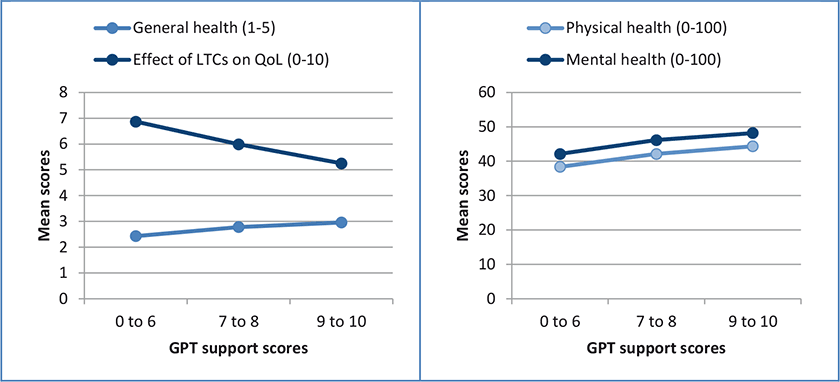

GPT support scores were similarly used to divide the participants into three groups; scores of 0 to 6, 7 to 8 and 9 to 10. Comparing mean scores on health and the effect of LTCs on quality of life across these three groups (Figure 4) demonstrates that those reporting a higher level of support had better self-reported health on all three measures and indicated their LTCs were having less impact on their quality of life.

Knowledge and choices after GPT consultations

Most people agreed that they knew more about their health after seeing a doctor or nurse at their general practice (71.8 per cent), with 12.2 per cent agreeing strongly. However, 14.5 per cent disagreed and 1.5 per cent disagreed strongly. Similarly, the largest group (67.7 per cent) agreed they could make better choices following a consultation, 14.1 per cent agreed strongly, 16.2 per cent disagreed and 1.9 per cent disagreed strongly. Scores on these two questions were moderately positively correlated with GPT support scores (r=.52 and r=.37 respectively), suggesting that people who agreed that they knew more, or that they could make better choices following a consultation, also felt better supported to manage their LTCs.

We looked at the group of people who had disagreed or disagreed strongly with both statements (n=57), and compared them to those who had agreed or agreed strongly with both statements (n=397). Those who disagreed were generally younger, less likely to have a care plan, to have more LTCs on average and have less income than those who agreed.

Changes wanted in consultations

In 2018, we added a question at the end of the GPT ratings to ask what, if anything, participants would change about their consultations with doctors/nurses at the general practice. This open-response format question generated a broad range of answers. Of the 174 respondents, 50 (28.7 per cent) indicated the question was not applicable, that they were unsure of what they would change, or said they were happy with the service provided. The other responses were grouped according to content, and the main themes were (with comments from participants):

Personalised care and respect:

Participants expected to be treated well in the consultation. They expected practitioners to have a pleasant approach, and to feel concern and interest and allow them to express their own thoughts and ideas. They also wanted to be shown respect, to be heard and accepted (not judged).

“Doctor listening to me, not looking at the computer. Telling me to come back next week if I still have a problem instead of addressing it at the time. Not prepared to discuss more than one problem.”

Access:

Many participants said the waiting time for getting an appointment was too long, many having to wait for weeks rather than days. This was particularly problematic when they wanted to see their own GP.

“Often hard to get an appointment with my GP as the practice is very large and very busy.”

Cost:

The cost of general practice consultations, repeat prescriptions and collecting medicines was frequently raised.

“Not everything is about money, they will charge you for everything they can, you cannot see the emergency doctor without going to the nurse first and they charge you for both.”

Time:

People identified the busyness of general practice as a problem. Some people felt “rushed” and others felt like a “nuisance”. More allocated time per consult was requested, as 15 minutes was not perceived to be enough to meet the needs of people with LTCs.

“Stop making me feel like I’m taking up their time and then wanting me out even though I haven’t been there for the allotted time.”

Care continuity:

Participants wanted consistency of care and having their own GP or nurse for the consultation was very important. Extended waiting times often meant that patients had to see other practitioners or locums.

“Being able to make appointment with original (normal) doctor and not seeing any doctors that are free at the time.”

Follow up:

Follow up was important, as it showed participants that practitioners cared about their progress.

“Follow up after certain time frame from the visit, just to check that you may (or may not) be improving.”

Discussion

It is clear from these results that most of the Talking About Health participants had received care from both GPs and practice nurses at their general practice, and about a third had seen one or more specialist nurses or a nurse practitioner (including CCN-LTCs). Clearly more people are now receiving care and support for their LTCs from nurses, rather than GP alone. This reflects the purposeful change introduced in our region a decade ago, with nurses promoted as being best placed to provide effective LTC care and self management support.

Although a large number of people were satisfied with their experiences, many good suggestions for consultation changes were offered. Many wanted a system that was more responsive to their needs as a person with at least one LTC. This included care continuity, reduced waiting times (both for an appointment and in the waiting room), more personalised support and lower costs. A recent survey of experiences with New Zealand health services found one in five of the 72,000 participants avoided a general practice appointment and one in five of the Māori/Pasifika respondents chose not to collect a medicine due to cost. Cost was more of a challenge for younger people and those with LTCs.4

In the Talking About Health study, experiences people had with doctors and nurses in general practice were considered to be good overall, and more positive experiences were associated with better self-reported health and LTCs having less impact on quality of life. However the experiences rated least well were those of particular relevance to people with LTCs who generally need more time, to be known as a person, have their social/living situation taken into account during consultations and have whānau included in care decisions. These are key components of holistic care and most could be addressed through a longer consultation and by providing ongoing self-management support. Using a “what matters most approach” in care discussions would be a great start to learning more about the individual and their life context.

LTCs consume 59 per cent of publically funded health expenditure and 13 per cent is due to multi-morbidity (the amount spent over and above the costs associated with specific conditions).5 Therefore reviewing the processes used to deliver LTC care and self-management support is essential – especially within general practice, the patient’s health-care home. For people to be good self-managers, they need to feel informed and have the knowledge, skills and confidence to care for themselves and to work in partnership with their health-care team to improve their LTC management.

Key points

- Almost everyone had seen a GP during the previous year and almost four-fifths had seen a practice nurse. Around a third had seen a specialist nurse or nurse practitioner at the practice and a third had seen a community clinical nurse (CCN-LTC).

- Consultation experiences were rated as good to very good overall. However, a quarter of the respondents rated their interactions with their GP, and a fifth their interactions with nurses, as less than good (very poor, poor or fair).

- Aspects of the consultation said to be done best were things that are integral to all types of consultations. Some of the aspects most relevant to people with LTCs – such as knowing the patient as a person, spending enough time, learning about broader social needs, and including whānau in decision-making – were considered to be less well done.

- A number of participants, Māori as well as non-Māori, noted that having their whānau included was not relevant.

- Overall LTC-related care and support from the GPT was rated as 7.9 out of 10 on average.

- Higher ratings of consultation experiences with doctors and nurses and higher ratings of support from the GPT were associated with better self-rated general, physical and mental health, and with LTCs having less impact on quality of life.

- Desirable changes to general practice consultation included more personalised care and respect, quicker access, lower costs, better follow up, more time and continuity of care.

Practice points

- Experiences with doctors and nurses were rated positively overall, but those rated least positively were things that were of particular relevance to an LTC population and consequently identify areas for improvement.

- Having a better understanding of what people are dealing with, in the context of their conditions and social situations, can enable practitioners and support people to know how they can best provide self-management support. Involving whānau and friends in consultations and care decisions can facilitate better use of self-management resources by patients. Therefore they should be actively encouraged to bring along a support person (who may well be waiting in the car) to be part of the consultation. This provides an opportunity to gain their input, educate and inform supporters and enhance the quality of support.

- Lack of time during the consultation is always going to be an issue for LTC patients, as most are on medications, requiring repeat prescriptions and follow up, and most have more than one condition, adding to management complexity. Perhaps patients could be taught to prepare for appointments, bringing a prioritised list of what they want to talk about and the confidence to ask important questions. Others have cultural requirements that may be better met by another practitioner such as an iwi or Māori provider. Thinking about the person in their entirety, and, therefore, who would be more likely to have the most time to support them and their whānau with their LTC management, is central to good care.

- Taking a “what matters most” approach,6 asking people what is important to them during the consultation, would address a number of our participants’ concerns. This would enable care to be personalised and respectful, and would increase practitioners’ understanding of individuals’ challenges. If you ask what is most important at any one time, the answer may surprise you, as it might not relate to their diabetes or respiratory health but might be concerns about caregiving, mobility or loneliness. All of which could be addressed.

Could more people be encouraged to sign up to the portal so they can contact their provider by email or see their reports and recent results?

- In light of the changes to mode of consultation encouraged by the COVID-19 situation, it is timely to consider what changes could be implemented into the new “business as usual” model for people living with LTCs. For example, could we increase the number of those with a care/action plan? Could more people be encouraged to sign up to the portal so they can contact their provider by email or see their reports and recent results? How could you change the way you do things to provide better self-management support for people with LTCs?

Claire Budge, PhD, is a health researcher for THINK Hauora. Since completing her PhD in psychology in 1996, she has conducted a wide range of health-related research projects, more recently on self-management issues for people with LTCs.

Melanie Taylor, RN, BASocSci, MN, is a nurse adviser, long-term conditions, for THINK Hauora. For the last 13 years she has focused on improving LTC management in primary care, with a particular interest in health redesign, self-management and health literacy.

References

- Taylor, M., & Budge, C. (2020). Talking about Health: Study overview and self-care challenges experienced by people with long-term conditions. Kai Tiaki Nursing New Zealand, 26(2), 20-23.

- Zwier, G. (2013). A standardised and validated patient survey in primary care: Introducing the New Zealand General Practice Assessment Questionnaire (NZGPAQ). New Zealand Medical Journal, 126(1372), 47-54.

- Hays, R. D., Bjorner, J., Revicki, R. A., Spritzer, K. L., & Cella, D. (2009). Development of physical and mental health summary scores from the Patient Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) global items. Quality of Life Research, 18(7), 873-80.

- Health Quality and Safety Commission New Zealand. (2019). New data shows cost as the main barrier to accessing health services.

- Blakely, T., Kvizhinadze, G., Atkinson, J., Dieleman, J., & Clarke, P. (2019). Health system costs for individual and comorbid noncommunicable diseases: An analysis of publicly funded health events from New Zealand. PLoS Med 16(1), e1002716.

- Barry, M. J., & Edgman-Levitan, S. (2012). Shared decision making – pinnacle of patient-centered care. New England Journal of Medicine, 366(9), 780–1.