The challenges faced by neonatal nursing teams around the motu have of late been compounded by the constraints of our health system, the socio-economic difficulties faced by our communities and capacity issues faced by many neonatal intensive care units (NICUs).

The challenges faced by neonatal nursing teams around the motu have of late been compounded by the constraints of our health system, the socio-economic difficulties faced by our communities and capacity issues faced by many neonatal intensive care units (NICUs).

Our day-to-day work is increasingly focused on the support and well-being of māmās and the wider whanāu, as well as the increasing complexity of the physical and technical care of pēpi.

Yet, at a time when many units are squeezed with up to 130 per cent occupancy, NICU across the country are experiencing significant understaffing. Some report they are 20 per cent down on what their staffing should be, according to safe staffing tool CCDM calculations.

This impacts on the quality of care we give whānau and pēpi. We are seeing increasing numbers of errors and incidents of direct harm. One NICU earlier this year reported 224 adverse incidents in six months — a 200 per cent increase. In their words, staff felt very unsafe.

At the same time, we are supporting families displaced from their homes to access specialist care for their pēpi, who are socially and culturally isolated, vulnerable, and often under financial, as well as emotional, stress.

We are also growing cultural awareness in our models of care for supporting whānau and fostering strong nurse-whānau relationships.

To manage, many NICU must do “patchwork” staffing, bringing in other nursing staff without specialist neonatal knowledge. This is risky for all concerned.

How to cope?

We explored some of these challenges in our recent symposium, Bouncing Back, held in Queenstown in May, which focused on resilience, recovery and innovation in neonatal care in Aotearoa.

As part of neonatal nurses college of Aotearoa (NNCA) progress towards actualising te Tiriti o Waitangi, we are also growing cultural awareness in our models of care for supporting whānau and fostering strong nurse-whānau relationships.

But speaking to neonatal nurse managers ahead of the symposium, Tōpūtanga Tapuhi Kaitiaki o Aotearoa – NZNO president Anne Daniels reminded us that the burden of resilience cannot fall solely on nurses, midwives and health-care assistants (HCAs).

Systemic change was needed to ensure the safety of nurses and minimise the harm we see and experience. Change was needed to ensure that we nurses can practise in safely-staffed workplaces, Daniels said — challenging us to hold our health leaders and Government to account, ensuring they reflect the values of te Tiriti.

Daniels suggested safe staffing would only be achieved with robust national data and monitoring — which could also feed into long-term nursing workforce planning.

The care given by neonatal nurses came at a price, she said. While rewarding, it is emotionally and physically demanding — and can also be heart-breaking. But she urged us to keep doing what we do, because it matters.

As well as supporting the growth and development of pēpi and their whānau, we also have a responsibility for our own growth.

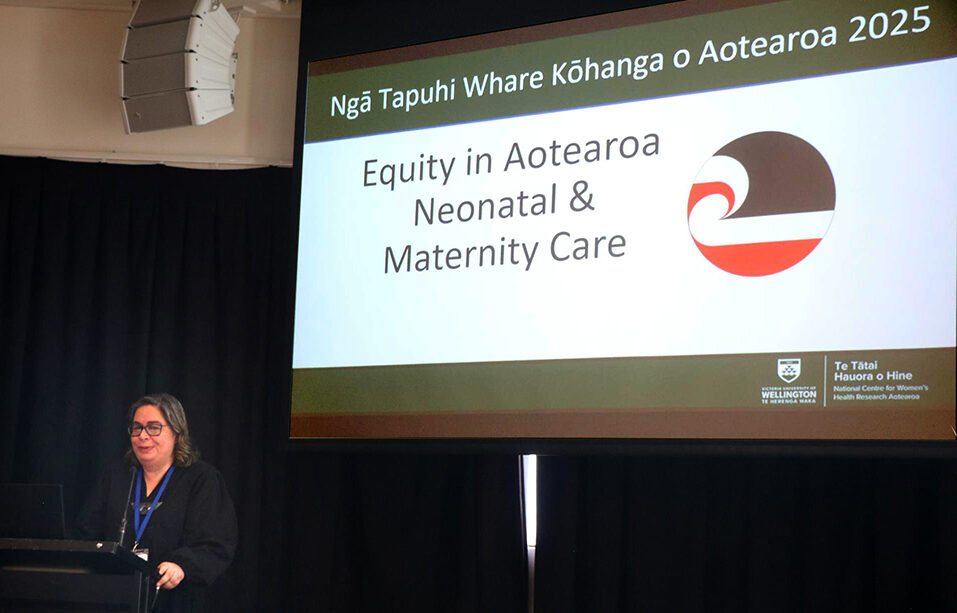

Otago neonatologist, paediatrician and researcher Liza Edmonds (Ngāpuhi, Ngāti Whātua) talked about how projected population growth showed that one in three children will be Māori by the 2040s.

Sharing the whakataukī, mā ngā pakiaka e tū ai te rākau — with strong roots a tree will stand — Liza emphasised that as neonatal clinicians as well as supporting the growth and development of pēpi and their whānau, we also have a responsibility for our own growth.

Only then are we likely to have stronger roots both for ourselves and the future of health care.

She suggested approaching Māori nursing and medical students might encourage people to become neonatal nurses or pediatricians to support the Māori neonatal workforce and health of our future tamariki.

These are confronting statistics that represent not only loss of life but the irretrievable interruption of whakapapa.

As a Māori doctor, Edmonds acknowledged the responsibility she felt for indigenous health. Her research work with the Health Quality and Safety Commission’s perinatal and maternal mortality review committee (now disestablished) found in the five-year period 2016-2020, that if mortality rates were the same for Māori as non-Māori, 188 pēpi and mama lives would have been saved.

These are confronting statistics that represent not only loss of life but the irretrievable interruption of whakapapa.

Social determinants (privilege), neglectful care (avoiding whānau we see as “difficult”), judgmental care (involving young mothers, people experiencing mental health challenges or substance use) and systemic barriers (access by NICU whānau to transport and childcare), all contributed to the disparities in neonatal and maternal mortality rates, Edmonds said.

Canberra neonatal research nurse Margaret Broom also discussed the need to put whānau and pēpi at the centre of care and design of NICUs.

One Mother to Another and the Little Miracles Trust shared the perspective of parents and whānau with a baby in NICU as they try to make sense of their experience.

Te kaikōmihana matua / chief children’s commissioner Claire Achmad talked about the barriers to whānau access to pēpi in NICU, particular for siblings, and how distressing this can be for both families and staff.

Dunedin neonatologist Lela Yap and Toronto neonatologist Mary Woodward broached moral distress and how neonatal staff can develop resilience in caring for neonatals amid periviability changes, and trying to balance the benefits and risks of treatment.

Our college representative on the Council of International Neonatal Nurses (COINN), Debbie O’Donoghue, described the history of COINN, of which NNCA is a founding member. COINN supports the economic and social needs of neonatal services across 181 countries, including the delivery of care, nursing workforce sustainability and outreach programmes.

- Juliet Manning is NNCA’s outgoing secretary, while Michelle Willows is incoming secretary.