Work readiness is a concept commonly used as an evaluation criterion for recruiting and selecting nursing graduates. Understanding this concept is valuable, not just to education providers, who must produce nursing graduates able to move seamlessly into practice, but also to health-care providers, who invest significant resources to help graduates develop competence levels required by the workplace.

The concept is also vital for new graduates themselves, who are entering a health-care environment whose complexity they find daunting.1

We undertook a study to evaluate the work readiness of new graduates from a New Zealand educational institution’s bachelor of nursing (BN) programme to ensure the compatibility of the programme’s objectives with the expectations of the BN profile, which lists the expected capabilities of a graduate. The focus of the research was to find out if there were deficiencies in the BN programme and whether changes to the curriculum were needed.

Quantitative data was gathered via surveys of expert nurses in three district health boards and of students in the transition phase at the end of their course, and qualitative data through focus group interviews with new graduates in their first few months of employment.

From the new graduates’ perspective, they were selective in who they would ask for help – they chose staff they felt were approachable.

This article reports in particular on one part of the study: the ability of new graduates to communicate clinical information, and their clinical decision-making skills. New graduates were concerned they were not taken seriously when reporting the deterioration of a patient to more senior staff, while senior nurses felt their communication skills could improve. Both the expert nurses and the new graduates emphasised the importance of having a supportive clinical environment for the new nurses to develop their confidence and skills, where they could ask for help they needed.

Ethics approval for the study was obtained from the ethics committees of the DHBs and of the researchers’ educational institution. At the time we started the project, there were no similar studies of new-graduate work readiness in New Zealand, although two theses have since been published.2,3

In 2011, Australian researchers Catherine Caballero, Arlene Walker, and Matthew Fuller-Tyszkiewicz,4 from Deakin University, embarked on a study to identify the attributes and characteristics of the work readiness of graduates and develop a scale to assess it. Their 167-item work readiness scale (WRS) was validated by a sample of 251 graduates across a range of disciplines. The scale was subsequently reduced to 64 items under four headings: organisational acumen, social intelligence, personal characteristics and work competence. Our research team used the work of Caballero et al as the springboard for an extensive literature search of CINAHL, Ebsco Host, Business Source Complete and MeSH databases. We used the search terms “work readiness”, “preparedness”, “skills gap”, “graduate gaps,” “graduate preparedness”, “unpreparedness”, “graduate perceptions” and “practice readiness” and examined 30 studies dating from 2007 to 2017.

From this background research, we developed four major themes to direct our research project. These were: “dimensions of work readiness”, “employability and work readiness”, “successful transition” and “experiences and perceptions of new graduate nurses”.

Three district health boards who employed graduates from the BN programme were approached to participate in the study, with one dominant employer of the educational institute’s graduates responding strongly to the invitation. Expert nurses from this employer were invited to take part in two rounds of a survey, to provide the study with insights into their expectations and experience of new graduates. The researchers felt that canvassing these senior clinicians would provide real-world knowledge from those who were familiar with BN graduates in their first post-registration employment.

The Delphi technique was used to canvas the opinions of these expert nurses.5 An “expert” nurse can be defined as one who is “expert in the area in which the researcher is interested”.5 The Delphi technique was designed to extract the views of a panel of experts using repeated rounds of questions. It is particularly useful in areas on which there is no scientific agreement or where contention might be expected.5,6 Its strength lies in its ability to offer a snapshot of expert opinion from a particular group “at a particular time” which can “inform thinking, practice or theory”.7 In this study, the expert panellists had between 10 and 30 years’ experience of being involved in employing new-graduate nurses in clinical practice. They included charge nurses, clinical nurse educators, clinical liaison nurses and those involved with running nurse-entry-to-practice (NETP) programmes.

The four research themes were used to develop the first round of 44 statements to be rated by these expert nurses in an online survey. A total of 22 expert nurses participated in round one of the survey. Of these, 17 participated in round two.

Weighted averages calculated from the responses to round one were considered for consensus of opinions on each statement. As well as rating each statement, the panellists could also provide qualitative comments in a text box to elaborate on their choices. Developed from both the quantitative and qualitative analysis, a 2nd round of statements drew further opinions from the participating panellists. From the 2nd round, an Alpha Cronbach analysis, with an 0.7 cut-off point, provided statistical verification of the strength of opinion from each panellist.

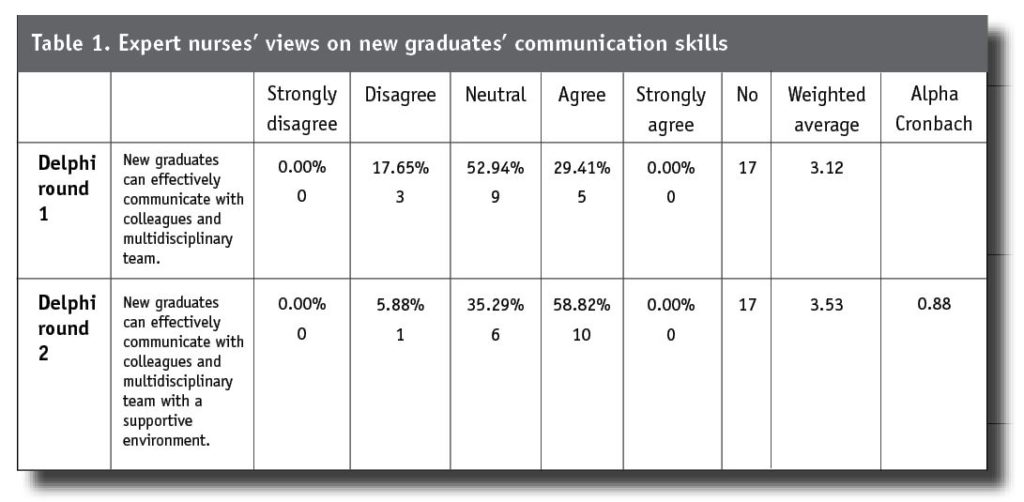

From the quantitative data, the majority of panellists in round one remained neutral in their opinion of new graduates being able to communicate effectively with the multidisciplinary team. In round two, most of the panellists (10/17) agreed that the new graduates could communicate effectively provided they were in a supportive environment. (Alpha Cronbach score of 0.88).

Data from the expert panellists’ surveys helped us develop a survey for BN transition students who had just completed their 12-week transition clinical experience. A total of 27 transition students answered the survey, which gauged how work-ready they felt prior to sitting their state examination and taking up registered nurse (RN) practice.

We also used focus groups of new graduates of the BN programme – who were in their first six months of employment post-registration — to gauge how work ready they felt they were as they began RN practice. From the breadth of data collection and analysis, this article focuses on new graduates’ communication and decision-making skills.

. . . some graduates lacked confidence to speak up and others had too much confidence and could appear challenging and aggressive.

A particularly dominant theme from the focus-group data was the new graduate’s ability to articulate their assessment of a patient’s health status when their patient was deteriorating. Most of the new graduates believed they were not taken seriously by more senior staff, even if their analysis was later proved accurate. The new graduates said they believed that more senior staff and the multidisciplinary team saw them as lacking the experience to evaluate the patient’s health accurately. This study found evidence that the new graduates were aware of their patient’s deteriorating health, but their ability to articulate clearly and succinctly their assessment and their concern in a manner that emphasised their knowledge was a weakness.

Data from the expert panellists showed they saw communication skills of the new graduates was an area that could be strengthened. The majority of panellists in round one remained neutral in their opinion of new graduates being able to communicate effectively with the multidisciplinary team. In round two, most of the panellists (10/17) agreed that the new graduates could communicate effectively provided they were in a supportive environment (Alpha Cronbach score of 0.88).

Comments from the panellists included that some graduates lacked confidence to speak up and others had too much confidence and could appear challenging and aggressive. It must be accepted that there is a broad range of abilities among new graduates, but graduates do need to have a basic ability to discuss their patients’ observations and concerns with the multidisciplinary team in an accurate and timely manner. One expert panellist commented that support was available for new graduates but many did not take enough responsibility to seek it.

“My experience is that many grads do not take enough responsibility for their role in communicating with me in regard to their (NETP) new to practice requirements despite being offered numerous avenues to do so. Communication is vital for safe and effective patient care. This is something a new graduate can build on but a good level of confidence in communication as a new graduate nurse is important from the outset”.

The expert panellists were asked several questions related to new graduates’ decision-making about their patients. One question related to new graduates ability to seek out information related to their patients’ care.

There was a relatively high internal consistency of agreement from the panellists, with 82.35 per cent (14/17) agreeing that new graduates could do this (Alpha Cronbach 0.76). Another question concerned thinking through clinical problems at a beginner’s level. Less than half the panellists agreed that new graduates could do this (8/17, 47.06%) with 41.18 per cent (7/17) remaining neutral on this area of new-graduate practice. Another question related to new graduates’ ability to problem-solve relevant to the clinical situation. In Delphi round one, most expert panellists remained neutral rather than giving an opinion on this (11/17, 64.71%), with only four (4/17, 23.53%) agreeing they could do this. For round two, a new statement was drafted — that “new graduates can problem-solve relevant to the situation but prefer to discuss it with their senior team members for a second opinion which is excellent”. The majority of panellists agreed that this was the case (10/17, 58.82%) and four strongly agreed (4/17, 23.53%) (Alpha Cronbach 0.64 level of internal consistency).

Both the expert nurses and the new graduates emphasised the importance of having a supportive clinical environment for the new nurses to develop their confidence and skills, where they could ask for help they needed.

The issues of decision-making and clinical judgement were further pursued with the transition students and the new graduates in their first six months of their practice. When the transition students were asked if they felt confident in making complex clinical decisions, 37 per cent agreed or strongly agreed that they were able to, as their RN preceptor had given them opportunity to practise the skill in their transition experience. However, 11.11 per cent disagreed or remained neutral, and 3.7 per cent strongly disagreed, saying they needed to gain more practice at articulating their clinical reasoning and their clinical decision-making for them to be able to graduate with confidence to do so. This identifies an area for strengthening in the current pre-registration experience of students.

Also, preceptors who supervise pre-registration students could be counselled to engage the students to articulate, in a professional manner, the current health status of their patients, identifying areas of concern based on sound clinical reasoning and evidence. The best place for preregistration students to gain confidence and the ability to succinctly describe situations where the health status of patients is deteriorating is in their transition clinical practicum alongside their supervising RN, prior to sitting the state registration examination.

Four focus groups were held with new graduates from the BN programme who were in their first six months of their practice, with one participant (T31.P1) being in the 2nd six months of her practice. Each group had between four and 10 participants. Analysis of the focus groups revealed a number of themes, with one in particular standing out: “managing challenging situations (coping strategies)”. This theme included clinical decision-making processes. In contrast to the expert panellists’ opinions, new graduates in the focus groups said they felt reasonably confident in their clinical decision-making.

Prioritising was part of the decision-making process. New graduates described prioritising their workload as challenging due to the number and acuity of their patients. Uppermost in their minds was patient safety. As one participant explained: “I just did what was most important at the time for the patient”. (T31.P1)

New graduates demonstrated they were able to think critically and use clinical reasoning to inform their decision-making. One participant (T32.P2) summed up this process by describing her thinking in a clinical situation concerning a patient diagnosed with dementia who was declining her regular medications:

“She [the patient] was due for her antibiotics . . . you need to build a rapport with them [patients diagnosed with dementia] and I had to have a better relationship in order to gain her trust but she did not know me. I’m trying to tell her this is for her infection but she doesn’t want to. You can’t do anything about it . . . you feel guilty that you know you want to treat this infection. I had to wait for her husband to come in who comes at 10 o’clock to give her medication because she will then take her medication. The husband said that she always takes the medication at home because she knows the medication . . . so involving the families” (T32.P2).

This clinical situation involves not only knowing the importance of maintaining a therapeutic level of the medication in the patient’s circulatory system, but also being aware that social factors affect the nurse’s ability to comply with correct practice. Such a situation is an added stressor to a new graduate.

New graduates also stated that when confronted with clinical situations that required problem-solving, they asked senior nursing staff to help them or they looked up organisational protocols. They also said they were resourceful and able to self-assess and identify deficiencies in their own knowledge. They were able to find out information essential to their patients’ care by reading up theoretical knowledge for themselves. As one new graduate stated:

“I am working in the theatre. So I feel like most of the stuff there wasn’t even mentioned in the classroom. So a lot of stuff, I have to go home and do my research and do my own study before I go to work the next day”. (T35.P3)

New graduates also identified that at times they were afraid, but knew how to seek help. If they found themselves in a situation that they felt they could not manage, they had no hesitation in asking for help. As one participant (T31.P1) stated: “ . . . it is better to ask when you are concerned about a patient than to do something that you think you know”. New graduates also appreciated an opportunity to debrief when faced with challenging clinical situations: “ . . . being able to talk about your problems and feelings with other people is very helpful”. (T31.P2)

On the whole, the expert panellists thought that new graduates needed to develop better communication skills, but if the new graduates felt they were in a supportive environment they were better able to communicate effectively. From the new graduates’ perspective, they were selective in who they would ask for help – they chose staff who they felt were approachable. One focus group participant described her experience in seeking help when confronted with a challenging clinical situation:

“I found there were barriers to communication just being new I guess, because people are much more willing to help you, and drop what they are doing, or prioritise your needs, if you have already developed a relationship with them. And you know, like build I guess interpersonal relationships within the team you work in, so being new, that has been a barrier to being able to communicate effectively”. (T35.P10)

In conclusion, the transition students in our study felt positive about their work readiness, and the new graduates in practice remained positive but with greater insight into areas where they needed to improve. Their insights mirrored those raised by the generic work-readiness researchers Caballero, Walker and Fuller-Tyszkiewicz,4 in their development of the work-readiness scale. Important elements of their work-readiness scale, such as “work competence” (including organisational ability, critical thinking, problem-solving, creativity and innovation) and “social Intelligence” (including teamwork/collaboration, interpersonal/social skills, adaptability and communication skills)8 were reiterated by the new graduates in this study. The new graduates felt that work competence — including organisational ability, critical thinking and problem-solving — was enhanced when they knew they were working in a supportive environment, when they could approach staff when uncertain, and could seek help if necessary. Their overriding concern was patient safety.

The new graduates said they believed that more senior staff and the multidisciplinary team saw them as lacking the experience to evaluate the patient’s health accurately.

Further, they felt that social intelligence — including team work/collaboration, interpersonal skills, adaptability and communication skills — depended on their familiarity with the context. For example, if the new graduate had done their transition experience in the area of practice where they were currently employed, it increased their confidence to practice. Conversely, if the new graduate felt unsupported, or out of their depth and perceived an oppressive organisational context, the feeling of being new undermined their confidence and comfort in speaking up.

If BN students at the transition stage were given the opportunity to share these insecurities with both peers and preceptors, it would likely help them develop better skills in articulating their clinical reasoning and judgment. Then, as new graduates, they would develop greater resilience in the face of “being new” as they began their careers as registered nurses.

- This article was reviewed by Sally Dobbs, RN, EdD, MSc, MAEd, who is the head of faculty at SIT2LRN at the Southern Institute of Technology, Invercargill.

Louise Rummel, RN, PhD, is a senior lecturer, academic/research, in the School of Nursing, Manukau Institute of Technology (MIT), Auckland. Sheona Watson, RN, MHSc, is a senior lecturer academic and quality lead at the MIT School of Nursing. Julie Beck, RN, MN, is clinical nurse director at Counties Manukau Health. Jane Kelly, RN, RM, is a senior lecturer academic and clinical lead at the MIT School of Nursing.

References

- Mellor, P., Gregoric, C., & Gillham, D. (2017). Strategies new graduate registered nurses require to care and advocate for themselves: A literature review. Contemporary Nurse 53, (3): 390-405. DOI: 10.1080/10376178.2017.1348903

- Cracknell, D. J. (2018). ‘Thrown in at the deep end’. A qualitative study with New Zealand new graduate nurses working in mental health. A dissertation for the degree of Master of Health Sciences. Centre for Post graduate Nursing Studies, University of Otago.

- Ferguson, D. (2019). What are the elements of work readiness in new graduate nurses in the New Zealand context. A professional consensus. A thesis submitted to Auckland University of Technology in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Health Science, School of Clinical Sciences. Faculty of Health and Environmental Science.

- Caballero, C. L., Walker, A., & Fuller-Tyszkiewicz, M. (2011). The work readiness scale (WRS): Developing a measure to assess work readiness in college graduates. Journal of Teaching & Learning for Graduate Employability, 2(2), 41-54. https://doi.org/10.21153/jtlge2011vol2no1art552

- Keeney, s., Hasson, F., & McKenna, H. (2011). The Delphi technique in nursing and health research. Wiley-Blackwell.

- Hsu, C., & Sandford, B. (2007). The Delphi Technique: Making sense of consensus. Practical Assessment, Research & Evaluation, 12, 1-8.

- Hasson, F., & Keeney, S. (2011). Enhancing rigour in the Delphi technique research. Technological Forecasting & Social Change, 78: 1695-1704. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2011.04.005

- Casner-Lotto, J., & Barrington, L. (2006). Are they really ready to work? Employers’ perspectives on the basic knowledge and applied skills of new entrants to the 21st Century US workforce. The Conference Board, Partnership for 21st Century Skills, Corporate Voices for Working Families, and the Society for Human Resources Management.