Introduction

In February this year, differential diagnosis became an expected competency for registered nurses (RNs) in New Zealand.1 This change recognises nurses’ skills in using clinical reasoning to formulate a prioritised set of possible diagnoses when assessing a patient.

Although the Nursing Council states that a differential diagnosis is not an “official” diagnosis, including differential diagnosis in the scope of nursing practice makes clear that nurses need an understanding of the diagnostic process and how clinical assessment contributes to diagnosis.

Diagnosis can be a powerful tool in health care. Through diagnosis, health problems, including disease states, are identified, leading to appropriate recommendations for treatment.

This article focuses on one potentially problematic aspect of the diagnostic process which is known as diagnostic overshadowing. This occurs where one diagnosis “overshadows” another, with the result that important health problems are not addressed. Our focus is on diagnostic overshadowing as experienced by people with mental health and substance use conditions (MHSUC).

We discuss why diagnostic overshadowing is problematic and offer some suggestions for avoiding it. Included are excerpts from recent New Zealand research2, 3 in which health consumers describe their experience of diagnostic overshadowing.

What is diagnostic overshadowing?

In the context of people with MHSUC, diagnostic overshadowing is the term used to describe a clinician’s misattribution of physical health symptoms to an existing mental health or substance use problem.

It is the phenomenon where clinicians overlook physical symptoms in a consumer with a history or diagnosis of MHSUC, or misattribute physical symptoms to an existing mental health condition.

A typical scenario might be where a consumer who has previously been diagnosed with depression presents to a health provider with abdominal pain. The health provider, noting the previous diagnosis of depression, then begins to focus on the person’s mood and mental state, without first taking an accurate history of the consumer’s pain symptoms.

In the following example, a consumer describes how a GP focuses on anxiety rather than her physical symptoms:

“My GP often tries to blame any physical problem I have on my anxiety. I know my own anxiety pretty well now, I know what it feels like and how it behaves. It frustrates me when my GP is not willing to investigate my symptoms and just says ‘it could be your anxiety’.”

(woman aged 26-35)

In another example, a consumer’s ankle pain was overlooked because she had a previous diagnosis of bipolar disorder. The consumer’s mental health diagnosis has “overshadowed” the assessment to the point where a full and accurate assessment is not undertaken.

“I went to seek help for a sore ankle, the doctor replied with a ‘tell me about your bipolar disorder’. Turns out I had a torn ligament, diagnosed by someone else. My treatment was delayed and I felt humiliated.”

(woman aged 36-45)

Related to diagnostic overshadowing is the concept of therapeutic overshadowing. This refers to inferior treatment or no treatment being offered to people with MHSUC because the clinician does not believe the consumer is capable of managing their treatment or recovery and/or that people with MHSUC have lower capacity to respond to treatment.

Consequences of diagnostic overshadowing

In New Zealand, people with MHSUC experience significantly worse health outcomes than members of the general population.4 These outcomes include delayed diagnosis, lower life expectancy and premature mortality.

Although some of the difference in mortality arises from “unnatural” causes (suicide, homicide and accidents), most of the excess mortality comes from “natural causes”: dying prematurely from physical health conditions including cardiovascular disease, respiratory disease, diabetes and cancer.4

These disparities are accentuated for Māori with MHSUC who experience higher all-cause mortality in addition to higher rates of hospitalisation for diabetes, injury/poisoning and general physical health conditions.5

In New Zealand, people with mental health and substance abuse problems experience significantly worse health outcomes than members of the general population.

Consequences of diagnostic overshadowing are more severe for people with more severe MHSUC (schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, moderate to severe depression) and can be illustrated by considering cancer diagnosis and survival. The concept of treatment overshadowing is illustrated in the case of cancer, discussed below.

Cancer diagnosis and survival

Although the incidence of many cancers is similar in those with MHSUC compared to the general population, mortality rates from cancer are higher for those with severe mental illness.6

In New Zealand, the risk of death from breast and colorectal cancer in those with a diagnosis of schizophrenia or bipolar disorder is significantly higher than the risk to members of the general population. People with MHSUCs are diagnosed later and are more likely to experience comorbidity.7

International evidence also suggests that people with MHSUC are less likely to receive adequate treatment for cancer.8 These health disparities are reflected in marked differences in survival.

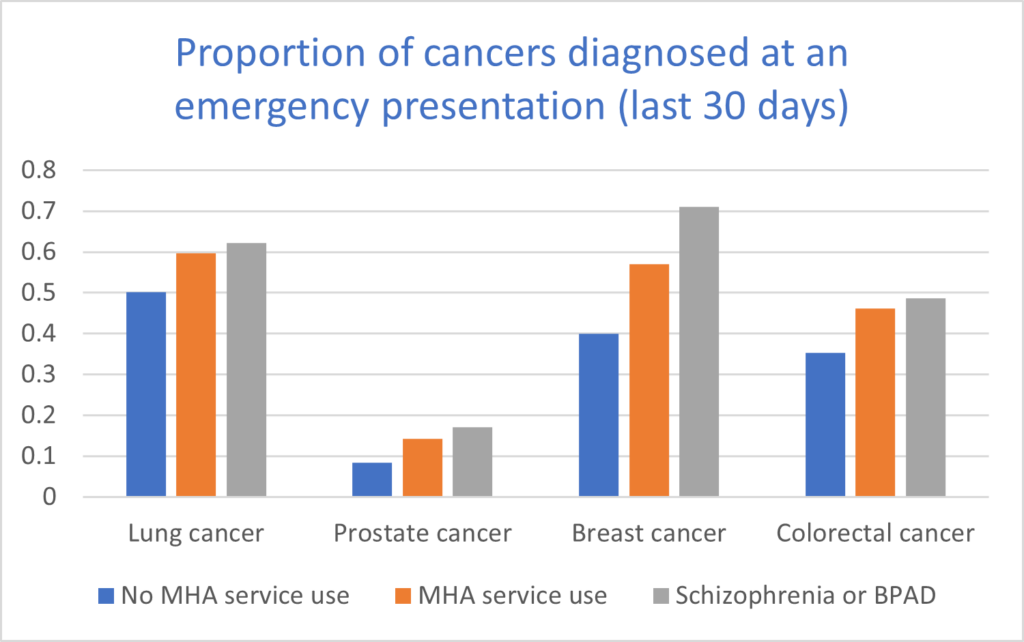

Timing of cancer diagnosis is also important. Receiving a cancer diagnosis as part of an emergency presentation (acute or emergency hospital admissions) is a marker of the timeliness of access to and quality of health care (from screening and diagnosis through to treatment and follow-up). High rates of diagnosis on presentation to emergency departments indicates lack of access to screening and early diagnosis.

In New Zealand, people using specialist mental health and addiction services are more likely to receive a diagnosis of prostate, lung, breast or colorectal cancer within 30 days of an emergency presentation.9 The likely reason for this is that this population have not been screened in primary care or have not been referred for specialist assessment. Emergency department presentation, usually for reasons unrelated to cancer, has become the pathway to cancer diagnosis.

Proportions of diagnoses on emergency presentation for each form of cancer compared by diagnosis and mental health service use are shown in Figure 1 (below). Differences are more marked for people with a diagnosis of schizophrenia or bipolar disorder.9

Figure 1. Proportion of cancers diagnosed as an emergency (emergency presentation within 30 days of diagnosis). MHA = Mental health and addiction; BPAD = Bipolar affective disorder. Graph shows rate ratios.

Figure 1. Proportion of cancers diagnosed as an emergency (emergency presentation within 30 days of diagnosis). MHA = Mental health and addiction; BPAD = Bipolar affective disorder. Graph shows rate ratios.

The importance of nursing assessment

A critical component of the nursing process is assessment, listening to a consumer’s concerns, observing signs and symptoms, attending to non-verbal cues, and exploring patterns that might help understand what is happening for them.

Assessment is defined by the Nursing Council1 as “A systematic procedure for collecting qualitative and quantitative data to describe progress and ascertain deviations from expected outcomes and achievements” (p9). The process of assessment is described as going “. . . beyond technical and organisational skills to a willingness to connect with the recipient.” (p10).

It is this process of connection that can help avoid the pitfalls of diagnostic overshadowing.

It is this process of connection that can help avoid the pitfalls of diagnostic overshadowing. In the New Zealand context, nursing assessment incorporates the values of the consumer within a bicultural, holistic framework.10 The hui process is recommended to create a respectful, culturally safe place in which nurses can listen to the concerns of consumers.11

Assessment should occur in the context of a therapeutic relationship based on trust, respect and empathy. That relationship should value lived experience and facilitate effective communication.

As nurses develop their practice in differential diagnosis, it will be important that they don’t position themselves as the experts on consumers’ problems but rather remain open to listening to and responding to consumers’ concerns.

A critical component of the nursing process is assessment, listening to a consumer’s concerns, observing signs and symptoms, attending to non-verbal cues, and exploring patterns.

Consumers consistently report collaboration as important in health care and appreciate clinicians’ engagement and listening to understand their health problems.12, 13 Accurate diagnosis is enhanced by the understanding and empathy developed within a therapeutic relationship.

“I changed to my current GP service because of the exceptional care, they are accommodating, listen rather than speak over you and work with you to find the best solution for you.”

(woman aged 26-35)

Avoiding diagnostic overshadowing

Avoiding diagnostic overshadowing starts with the clinician using critical self-reflection and becoming aware of whether bias is affecting their assessment. Sources of bias could be observations of the practice of experienced nurses or other professionals, societal views about people with MHSUC, or ideas encountered in education programmes.

Nurses and other health professionals share many of the biases common in the general public and so, without the opportunity for critical self-reflection, are likely to introduce those biases into their practice.

One specific strategy to minimise overshadowing is to take the approach that symptoms should be treated the same in all patients, including those with a history of MHSUC.

The benchmark for practice is that consumers with MHSUC should receive the same assessment for a physical symptom as those without MHSUC, even if a psychosomatic cause may be higher on the differential diagnosis list.

Another strategy is to share diagnostic uncertainty with the consumer.

Consumers want to be listened to, validated, taken seriously and have the same consideration and investigation for a physical cause for their symptoms as someone without a history of MHSUC.

Another strategy is to share diagnostic uncertainty with the consumer.14 As clinicians, we are often unsure of what an accurate differential diagnosis is. We may not have sufficient history, a consumer may be uncomfortable about sharing aspects of their health, there may be a need for laboratory tests, or we may want to observe to see how symptoms evolve.

In such cases uncertainty can be shared with the consumer, with a discussion on the best plan of care, and a time for review.

Structural aspects of diagnostic overshadowing

Nursing practice occurs within a social context, in which there are prevailing narratives about MHSUCs, as well as other factors that relate to a person’s perceived social level — factors that have an impact on health experience and health care.

In addition to discriminatory attitudes towards people with MHSUC,3 factors such as social deprivation, racism, sexism and resource constraints all shape health care and nursing practice.

Nurses share the cultural resources of their society, including attitudes to people with MHSUC, racism and sexism. In addition, nurses practise within a context of limited resources and institutional policies which also have an impact on practice.

In a health setting which is understaffed, and with a restricted range of services, nurses may be under pressure to make decisions quickly. In such circumstances it is less likely that nurses will have the opportunity to critically reflect on their practice and on how their decision-making is influenced by unconscious bias.

In a health setting which is understaffed, and with a restricted range of services, nurses may be under pressure to make decisions quickly.

Nurses, like other health professionals, are likely to fall back on familiar heuristics (rules of thumb) to make quick decisions. Nursing as a profession therefore has a responsibility to ensure that health service resourcing and policies support nurses to undertake sound clinical assessments and not uncritically follow short cuts in the assessment process.

A group of researchers led by psychiatrist and educator Javeed Sukhera have described how discriminatory attitudes can become incorporated into an organisation’s processes as “structural stigma” .

They define this term as ” . . . how inequity is manifested through rules, policies, and procedures embedded within organizations and society at large. Structural stigma is also prominent within clinical learning environments and can be transmitted through role modeling, resulting in inequitable treatment of vulnerable patient populations.”15 (p127)

These authors propose a four-part model for addressing structural stigma. Their model is based on a clinician using critical reflection, both on their own individual practice and on structural aspects of the practice setting. The model is summarised below in Table 1.

Table 1. A proposed framework for addressing structural mental health and substance use stigma in education for health professionals (adapted from Sukhera et al., 2022)15

| Component | Focus | Example |

| Recognise | Recognising how structural stigma manifests during care processes | During handover a consumer with a history of substance use is admitted with pain. One nurse refers to the consumer’s request for pain relief as “drug seeking”. Another nurse comments that other consumers with similar presentations require pain relief and argues that both consumers should receive the same treatment. |

| Reflect | Reflecting critically on how assumptions, values, and biases underpin systems of care | A consumer with a MHSUC is admitted from the emergency department with a relapse of a respiratory disorder precipitated by not taking prescribed medication. Rather than blame the consumer for being “non-compliant”, the charge nurse encourages nurses to consider whether factors such as cost or access to transport might have contributed to the consumer’s relapse. |

| Reframe | Reframing situations to highlight structural components and enhance connection | A consumer on a medical ward has a diagnosis of schizophrenia and is referred to by some staff as “a schizophrenic”. An alternative framing of “a person with severe mental health problems” is used instead of the diagnostic label. |

| Respond | Role modeling structural humility and by advocating for structural change | Nurses in a primary care clinic engage in community-level advocacy, including codesign of an initiative to ensure consumers with MHSUC have access to exercise programmes to improve their physical health. |

The role for nursing education

Nursing education programmes have a role to play in raising awareness of diagnostic overshadowing and raising faculty and students’ awareness of the problem, and how to avoid it. Beginning with learning the practice of therapeutic relationships, education can also help students develop the critical self-awareness needed to address discrimination and unconscious bias.

In New Zealand, nursing education can learn much from the teaching of cultural safety, which begins with reflection on one’s own identity and place within practices of colonisation in New Zealand.16

The skill of critical self-awareness is readily transferable to differential diagnosis. Nurses providing preceptorship in clinical practice can also help students develop awareness of diagnostic overshadowing by exploring with students examples of bias in the assessment process. These can include, for example, how the nurse’s own health experience might influence her perception of a consumer’s presentation.

Conclusion

New competencies for nursing practice in New Zealand provide an opportunity for reflection on the role differential diagnosis plays in clinical practice, the problem of diagnostic overshadowing with people with MHSUC, and strategies for preventing bias in the diagnostic process.

A wide range of information and resources to help nurses develop their practice to avoid discrimination and promote the physical health of people with MHSUC is available at the Equally Well website.

Addressing diagnostic overshadowing has the potential to improve inequities in health outcomes experienced by people with MHSUC and to promote person-centred nursing care in the context of a therapeutic relationship.

Anthony O’Brien, RN, PhD, is an associate professor in the nursing school at the University of Waikato.

Carolyn Swanson, FRANZCP, is the principal advisor for mental health, and service user lead at Te Pou.

Debbie Peterson, MA(App), PhD, is a senior research fellow in the Suicide and Mental Health Research Group and Department of Psychological Medicine at the University of Otago.

Ruth Cunningham, MBChB, PhD, is a public health physician and research associate professor in the Department of Public Health, University of Otago.

Stefan Heinz, RN, is a nursing lecturer at the University of Waikato.

- This article was reviewed by Lynere Wilson, RN, PhD, who is a lecturer in mental health at the Department of Nursing, University of Otago, Christchurch.

References

- Nursing Council of New Zealand. (2025). Standards of competence for registered nurses.

- Cunningham, R., Imlach, F., Haitana, T., Clark, M. T. R., Every-Palmer, S., Lockett, H., & Peterson, D. (2024). Experiences of physical healthcare services in Māori and non-Māori with mental health and substance use conditions. Australian & New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 58(7), 591-602.

- Cunningham, R., Imlach, F., Haitana, T., Every-Palmer, S., Lacey, C., Lockett, H., & Peterson, D. (2023). It’s not in my head: a qualitative analysis of experiences of discrimination in people with mental health and substance use conditions seeking physical healthcare. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 14, 1285431.

- Cunningham, R., Sarfati, D., Peterson, D., Stanley, J., & Collings, S. (2014). Premature mortality in adults using New Zealand psychiatric services. New Zealand Medical Journal (online), 127(1394).

- Monk, N. J., Cunningham, R., Stanley, J., Crengle, S., Fitzjohn, J., Kerdemelidis, M., Lockett, H., McLachlan, A. D., Waitoki, W., & Lacey, C. (2024). The physical health and premature mortality of Indigenous Māori following first-episode psychosis diagnosis: A 15-year follow-up study. Australian & New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 58(11), 963-976.

- Hill, S., Sarfati, D., Blakely, T., Robson, B., Purdie, G., Chen, J., Dennett, E., Cormack, D., Cunningham, R., Dew, K., McCreanor, T., & Kawachi, I. (2010). Survival disparities in Indigenous and non-Indigenous New Zealanders with colon cancer: the role of patient comorbidity, treatment and health service factors. Journal of Epidemiology & Community Health, 64(2), 117-123.

- Cunningham, R., Sarfati, D., Stanley, J., Peterson, D., & Collings, S. (2015). Cancer survival in the context of mental illness: a national cohort study. General Hospital Psychiatry, 37(6), 501-506.

- Murphy, J. F., Amin, L. B., Celikkaleli, S. T., Brown, H. E., & Tapan, U. (2024). Disparities in cancer care in individuals with severe mental illness: A narrative review. Cancer Epidemiology, 93, 102663.

- Cunningham, R., Stanley, J., Imlach, F., Haitana, T., Lockett, H., Every-Palmer, S., Clark, M. T. R., Lacey, C., Telfer, K., & Peterson, D. (2024). Cancer diagnosis after emergency presentations in people with mental health and substance use conditions: a national cohort study. BMC Cancer, 24(1), 546.

- Cameron, M., Foxall, D., & Holman, G. (2023, Aug 2). Mahere hau — an integrated bicultural nursing assessment framework. Kai Tiaki Nursing New Zealand.

- Minton, C., Burrow, M., Manning, C., & van der Krogt, S. (2022). Cultural safety and patient trust: the Hui Process to initiate the nurse-patient relationship. Contemporary Nurse, 58(2-3), 228-236.

- Ross, L. E., Vigod, S., Wishart, J., Waese, M., Spence, J. D., Oliver, J., Chambers, J., Anderson, S., & Shields, R. (2015). Barriers and facilitators to primary care for people with mental health and/or substance use issues: a qualitative study. BMC Family Practice, 16, 1-13.

- Sturman, N., Williams, R., Ostini, R., Wyder, M., & Siskind, D. (2020). ‘A really good GP’: Engagement and satisfaction with general practice care of people with severe and persistent mental illness. Australian Journal of General Practice, 49(1/2), 61-65.

- Cranley, L., Doran, D. M., Tourangeau, A. E., Kushniruk, A., & Nagle, L. (2009). Nurses’ uncertainty in decision‐making: A literature review. Worldviews on Evidence‐Based Nursing, 6(1), 3-15.

- Sukhera, J., Knaak, S., Ungar, T., & Rehman, M. (2022). Dismantling structural stigma related to mental health and substance use: an educational framework. Academic Medicine, 97(2), 175-181.

- Hughes, M. (2018). Cultural safety requires ‘cultural intelligence’. Kai Tiaki Nursing New Zealand, 24(6), 24-25.