Hutia te rito o te harakeke

Kei hea te kōmako, e kō?

Kī mai ki ahau

He aha te mea nui

He mea nui o tēnei ao?

Māku e kī atu kia koe

He tangata, he tangata

Background

Waikato nursing leaders have developed a new nursing programme at the University of Waikato — Te Whare Wānanga o Waikato. Underpinned by te Tiriti o Waitangi,1 the programme aims to support equitable health outcomes for the region’s Māori and rural population.

Additionally, those developing the curriculum were responding to clear direction from the Government for a broad and collaborative approach to meeting mental health needs in Aotearoa.2

Two pre-registration nursing courses were launched at the University of Waikato in 2021 — a three-year bachelor of nursing, and a two-year master of nursing practice course for students who already have another degree. Both the bachelor and masters curricula aim to provide an integrated programme with “mental-health-in-nursing” embedded from day one.3

Rather than mental health being siloed in one section of the nursing programmes, at Waikato mental health skills are integrated into all parts of the curricula, based on the belief that physical and mental health are intertwined and that a truly comprehensive nurse needs mental health skills that could potentially be used in any nursing interaction.

This article explains how the authors developed a health assessment approach that supports the growth of a truly comprehensive nurse, who intentionally has a whole-person view and who places the health consumer and whānau at the centre of their care.

The interrelationship between mental and physical health is not a new concept to nursing practice in Aotearoa;4 nor is the understanding that many dimensions — including ecological, environmental and social factors — contribute to overall well-being.5, 6

Strong evidence highlights that poor physical health is directly linked to mental health problems including depression, and social challenges.7 There are clear links between mental health conditions and an increased risk of poor physical health, specifically apparent in rates of diabetes, respiratory conditions and cardiac disease.7, 8, 9

At the University of Waikato, we have emphasised looking at health and well-being in people and communities through a holistic Māori lens. This has led to us developing a curriculum in which the assessment of mental well-being is integral to comprehensive health assessment, which emphasises “mental-health-in-nursing” skills, and which breaks down barriers between physical and mental health nursing care in all practice settings.

There are clear links between mental health conditions and an increased risk of poor physical health, specifically apparent in rates of diabetes, respiratory conditions and cardiac disease.

Assessment skills are foundational to nursing practice; the ability for nurses to accurately and efficiently assess and interpret findings is essential in providing safe, appropriate and effective care.10

The priority of assessment is identified clearly in the scope of practice for all registered nurses (RNs) in Aotearoa. RNs use their “knowledge and complex nursing judgment to assess health needs and provide care”.11 To assess a client’s needs in a way that is culturally responsive and cognisant of the whole person and their whānau environment requires a comprehensive and intentional approach to nursing assessment and practice.

Structured assessment frameworks provide essential guidance to nursing students as they develop their clinical reasoning skills.10 However “health assessment” has traditionally been closely linked with physical assessment, from which there is a focus on developing physical assessment skills.12

In our undergraduate programme, we have integrated “mental-health-in-nursing” skills into the curriculum and the assessment frameworks we teach, to help meet the holistic and wellbeing needs of patients.

An integrated approach

Developing an integrated approach to health assessment

The development of an integrated approach to health assessment in the curriculum was initially iterative — an ongoing process where the lecturers were refining ideas through discussion, teaching together, and trialling. We quickly identified that there were three elements to our way of working:

-

- lecturer collaboration and co-design of curriculum,

- co-delivery of lectures and tutorials, and

- use of a nursing framework to guide thinking in health assessment.

The first two elements required a willingness among staff to invest time into exploring and understanding our different practice backgrounds and our shared values, and developing a collective understanding of what specific skills and knowledge students would require to be able to reflect our intended graduate profile.

Graham Holman Thirdly, we aimed to develop an assessment framework to underpin an integrated approach to assessment that can be scaffolded over the length of the degrees.

The framework, underpinned by Māori models of health, aims to support holistic assessment and provide an integrated structure. Aspects of a bicultural approach and mental health are interwoven into existing approaches to health assessment.

Although there are existing frameworks for health assessment in physical and mental health specialties, we have aimed to develop one framework that can be adapted and implemented across different contexts and clinical settings.

Our intention is to shape this framework around “aromatawai”. The word “aro” means to take heed, take notice of, pay attention to and to consider; “mata” can mean face or surface, and “wai” means water.

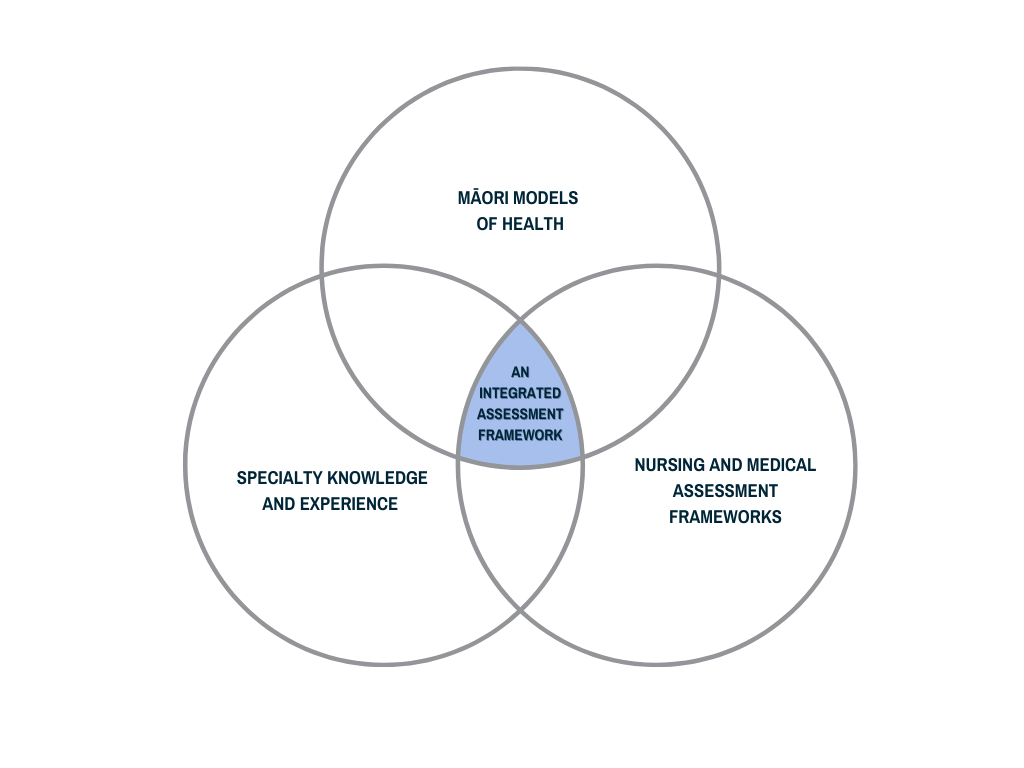

“Matawai” means to look closely, to scrutinise, to inspect and to examine. This idea is very important when considering wairua, whānau, hinengaro, tinana, whenua and reo. Figure 1 (below) illustrates the key components that contributed to the development of a unique and still evolving integrated nursing assessment framework at the University of Waikato.

Figure 1: Development of an integrated assessment framework

Figure 1: Development of an integrated assessment frameworkAn integrated framework

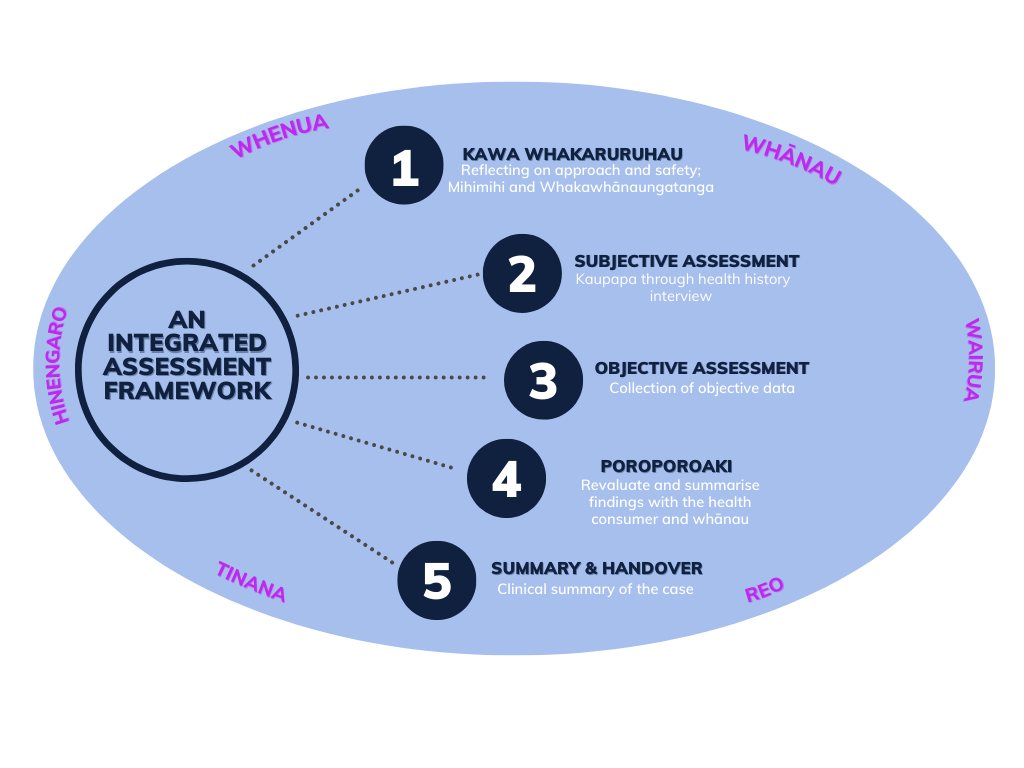

The conceptual assessment framework is structured in a way that is recognisable to registered health professionals. Its five broad sections are reflected in most approaches to comprehensive nursing assessment and include:

-

- preparing for the assessment,

- a health history interview,

- focused assessment,

- closing of the assessment, and

- summary (as outlined in figure 2).

However, there are key differences with applying an integrated approach. Students are encouraged to structure their thinking and approach to comprehensive assessment by making an intentional connection with individuals and whānau.

At the beginning of an assessment, students practice preparation through an approach that asks them to reflect both inwardly and outwardly. Early parts of the curriculum focus on developing the students’ understanding of their own personal values, worldviews and biases.

They are also encouraged to look outwardly at their surroundings, assessing the environmental and contextual safety for both themselves and the health consumer.

Our framework is informed by the hui process and the Meihana model of clinical assessment. These two models are based on Māori values which emphasise the importance of establishing and maintaining a trusting and responsive nurse-patient/whānau relationship.13, 14

Recent publications have highlighted the importance of the health professional-health consumer relationship in terms of cultural responsiveness. They have also noted the relevance of the hui process in guiding conversations about that with nursing students in Aotearoa.13, 14, 15 Understanding and implementing the hui process is crucial for relationship-building with health consumers.

Figure 2: An overview of an integrated assessment framework

Consideration of mental and emotional well-being, and the importance of mental- health-in-nursing skills are reflected in the framework. This helps students apply the ideas of holistic well-being in their everyday assessment practice.

Drawing on principles of mental health-focused assessments, the framework prompts students to think about safety for both the nurse and health consumer when conducting interviews. It also encourages developing rapport and from that a shared understanding of the issues.16 We have used assessment language and terminology that is inclusive, non-stigmatising, and focused on the health consumer experience.

The framework encourages developing rapport with the health consumer and from that a shared understanding of the issues. Photo: Adobe Stock. Another key difference in Waikato’s approach is the inclusion of a “mental state assessment” (MSA). Although an MSA is often undertaken when a mental health or neurological assessment is clinically indicated, the framework taught at Waikato considers the information obtained from an MSA as equally important as vital signs and other objective data.

Therefore, students are encouraged throughout the assessment to be reflecting on a person’s mental wellbeing and to be prepared to explore that dimension of health in all settings.

Delivering an integrated approach in health assessment

Terminology and teaching principles

Close attention is paid to the terminology we use when teaching comprehensive assessment. For example, we have moved away from using the phrase “presenting complaint” or similar, to encouraging students to seek to understand the kaupapa of the presentation and the purpose of the encounter.

This is important to the philosophy of the curriculum because we aim for our students to understand that the stated reason for referral or the priority of the assessing health professional may be different to that of the health consumer or whānau, and that this must be captured and understood.

We discuss the concept of focused assessment of systems or needs, rather than a generic term such as “physical assessment”.

We have moved away from using the phrase ‘presenting complaint’ or similar, to encouraging students to seek to understand the kaupapa of the presentation and the purpose of the encounter.

The delivery and facilitation of learning is also undertaken in an integrated way. To facilitate students’ learning about the framework, we use a number of teaching principles, including co-teaching, ako, scenario-based learning and incorporating clinical practice.

Teaching in collaboration (where two lecturers develop course content together and/or teach a class together) takes advantage of the different strengths, skills and cultural perspectives of lecturers from different specialties. Collaborative teaching not only enhances the delivery of theory, but also creates an interactive and potentially more inclusive learning experience.

Based on the concept of ako, course developers value the importance of recognising the knowledge that both students and teachers contribute.17 Co-delivery allows for a more interactive approach in which facilitators encourage students to share their knowledge – this is particularly evident with conversations about health history.

The structure of the clinical practice hours and the theory blocks enables students to bring experiences of using the framework back to the campus. Through reflective practice and group discussion, both educators and students share their experience, understanding, and perspective.

Closing the gap between theory and clinical practice is a common focus in nursing education. The Waikato programme’s increased clinical practice hours — 700 more than the 1100-hours minimum required by the Nursing Council — enables students to regularly apply the theory of this integrated framework, adapting it to the context they encounter in a range of placement settings.

Where to from here

The holistic framework guides our students’ thinking so they can understand their role in reshaping health services in a way that responds to the needs of our communities.

With the application of kawa whakaruruhau to this conceptual framework, our intention is to continue to evaluate and adapt our teaching principles of this integrated approach to nursing assessment.

The development of this conceptual framework has also supported conversations between colleagues about what bicultural integration looks like in the programme. Teaching the framework, and specifically, the intent behind the hui process, has strengthened colleagues’ understanding of a te ao Māori view and the importance of developing that shared understanding in relation to the programme’s aims.

Future development of the framework will include collaboration with the recently appointed Poutumatua Pasifika (Tausisoifua) to broaden the inclusivity and co-ownership of this approach.

We also intend to extend the teaching of this approach into post-graduate education, including the critique of how assessment of cultural and mental health needs are captured and addressed.

This 2021 photo, published in Kaitiaki Nursing New Zealand, shows the first intake of students in the new undergraduate nursing degree programme at the University of Waikato. It was accompanied by the article Nurses ‘can do more’ in mental health.

Michelle Cameron, BN(hons), PhD candidate, is co-ordinator of the masters of nursing practice and a senior lecturer in Te Huataki Waiora — the School of Health, at the University of Waikato.

Donna Foxall, BN, MN is a pūkenga matua/senior lecturer in nursing in Te Huataki Waiora — the School of Health, University of Waikato.

Graham Holman, RN, MNurs(hons), is a senior lecturer in nursing in Te Huataki Waiora — the School of Health, University of Waikato.This article was reviewed by Sally Dobbs, RN, MSc, EdD, former head of the nursing school at the Southern Institute of Technology (SIT) and now SIT’s head of faculty for SIT2LRN and Telford.

References

- Ministry of Health – Manatū Hauora. (2020). Whakamaua: Māori Health Action Plan 2020-2025.

- Ministry of Health – Manatū Hauora. (2020). He Ara Oranga Response.

- Longmore, M. (2021). Nurses ‘can do more’ in mental health. Kaitiaki Nursing New Zealand, Sept 1.

- Roberts, R., Lockett, H., Bagnall, C., Maylea, C., & Hopwood, M. (2018). Improving the physical health of people living with mental illness in Australia and New Zealand. Australian Journal of Rural Health, 26(5), 354-362.

- World Health Organization. (2009). Milestones in health promotion statements from global conferences.

- Durie, M. (1998). Whaiora: Māori Health Development (2nd ed). Oxford University Press.

- Doan, T., Ha, V., Strazdins, L., & Chateau, D. (2022). Healthy minds live in healthy bodies – effect of physical health on mental health: Evidence from Australian longitudinal data. Current Psychology.

- Wheeler, A. J., McKenna, B., & Madell, D. (2014). Access to general health care services by a New Zealand population with serious mental illness. Journal of Primary Health Care, 6(1), 7-16

- Te Pou. (2020). Achieving physical health equity for people with experience of mental health and addiction issues: Evidence update.

- Munroe, B., Curtis, K., Considine, J., & Buckley, T. (2013). The impact structured patient assessment frameworks have on patient care: an integrative review. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 22(21-22), 2991–3005.

- Te Kaunihera Tapuhi o Aotearoa — Nursing Council of New Zealand. (2022). Tapuhi Kua Rēhitatia Registered Nurse Scope of Practice.

- Egilsdottir, H. Ö., Byermoen, K. R., Moen, A., & Eide, H. (2019). Revitalizing physical assessment in undergraduate nursing education — what skills are important to learn, and how are these skills applied during clinical rotation? A cohort study. BMC Nursing, 18, 41.

- Minton, C., Burrow, M., Manning, C., & van der Krogt, S. (2022). Cultural safety and patient trust: the Hui Process to initiate the nurse-patient relationship. Contemporary Nurse: a Journal for the Australian Nursing Profession, 58(2-3), 228-236.

- Pitama, S., Huria, T. & Lacey, C. (2014). Improving Māori health through clinical assessment: Waikare o te Waka o Meihana. New Zealand Medical Journal, 127(1393), 107-119.

- Al-Busaidi, I. S., Huria, T., Pitama, S., & Lacey, C. (2018). Māori indigenous health framework in action: Addressing ethnic disparities in healthcare. New Zealand Medical Journal, 131(1470), 89-93.

- O’Brien, J. A., & Allman, A. (2021). Mental health assessment. In K. Foster, P. Marks, A. J. O’Brien, & T. Raeburn (Eds.), Mental Health in Nursing (5th ed., pp 109-131). Elsevier.

- Sewell, A., Cody, T.-L., Weir, K., & Hansen, S. (2018). Innovations at the boundary: an exploratory case study of a New Zealand school-university partnership in initial teacher education. Asia-Pacific Journal of Teacher Education 46(4), 321-339.