He spoke in a quiet, measured voice, to a hushed audience, about the time he walked to the top of his maunga with his koro.

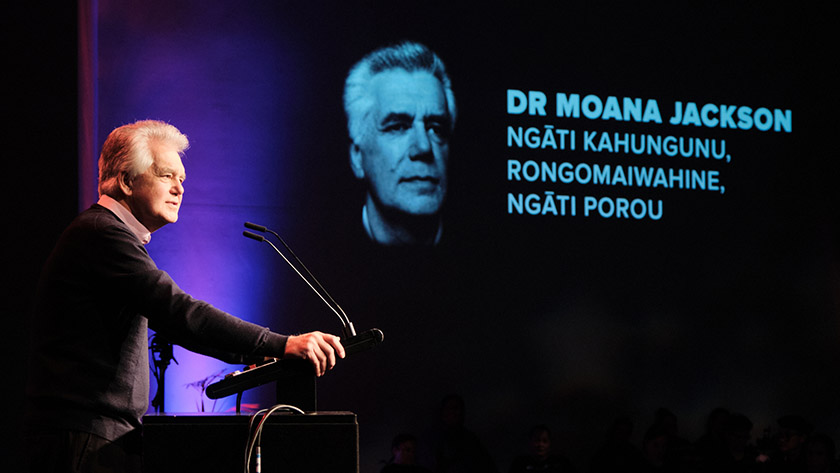

Moana Jackson – scholar, lawyer, activist, and leader – delivered a powerful address, interweaving memory, experience and years of research, to a mesmerised audience at the Indigenous Nurses Aotearoa Conference 2021.

With an eye to the conference theme, “heeding the call of the maunga”, Jackson told the audience of his koro’s advice.

“It’s not enough just to say what your maunga is in your pepeha… but find the time, at some time, to ‘touch the maunga’. And if it’s too high to climb, just be with it for a while.”

He recalled his visit as a youngster to Kahurānaki, in Hawke’s Bay, with his koro for the first time.

Kahurānaki, Jackson said, was not as grand or majestic as Hikurangi. It didn’t tower in the sky like Aoraki, he said.

“But it’s our maunga, and so it’s the best maunga in the world.”

They passed five “story stones” on the way up, marking spots where his koro would stop and share stories with him.

Jackson used figurative marker stones to guide the audience on its own journey: an examination of where Māori might look, to heed to the call of their maunga.

The first marker, he called the rock “of knowing where to begin”.

Whatever struggles and aspirations Māori had, it was always important “to know our beginnings”.

“To know where we have come from, to know the legacies that our tipuna have left. To know the struggles that we have had.”

He recalled the likes of Irihapeti Ramsden who first raised the idea that Māori nurses might be a group worthy of recognition in its own right.

“She developed the idea of cultural safety as part of the educational training of nurses, but that was a difficult struggle.”

Those beginnings led to the likes of the conference where he was now speaking, he said.

The second marker was the rock of “knowing who has come before us – upon whose shoulders we stand”.

These were the “brave and courageous” people who paved the way to the present.

“And many of them have been nurses, whom you will know I’m sure, or know their history.”

These people, who fought to preserve te reo Māori, battled domestic and international injustices, or improved the place of Māori in nursing, should be recognised.

“I think if we can find, in our own way, those people whose shoulders we wish to stand upon, acknowledge the contribution that they have made the path somehow easier for us, then that’s a worthy step in heeding the call of the maunga.”

The third rock on the maunga was knowing “where our people are at now”.

Māori were at a crossroads – there was a danger that progress could be taken away, and victories, after long struggles, denied.

“I have been concerned in the last little while, about how the overt racism towards our people has begun to resurface.”

This included the like of insults, “some quite vicious and nasty attacks”, on Māori women who had reclaimed their moko kauae.

Despite successes, it was important to realise that the fight was not over.

Māori still fared worse in healthcare, education and the criminal justice system. “So while we are at a better place than we were 20 or 30 years ago, we always need to be honest about where we are at.”

The next marker rock on the journey was called the rock of “where we might go”, Jackson said.

It was important to have aspirations and ambitions.

‘Indigenous peoples are proportionately the most represented in prison.’

He spoke of his years-long research examining why Māori made up such a large proportion of prison populations. Māori men comprised more than 52 per cent of the male population; while more than 60 per cent of the female population were Māori.

There were similar realities in Australia, Canada and the US, he said. “Indigenous peoples are proportionately the most represented in prison.”

The thrust of his collaborative research changed to the question of why countries with a history of colonisation imprisoned so many indigenous people.

When you switched to that starting point, the research headed in a “quite different direction”, he said.

“Because it seems to me that part of the colonising process was to confine and control the tangata whenua, so that their lands, their resources, could be taken.”

That manifested in the criminal justice system, “the building of prisons on land which had never known the idea of prisons”.

Jackson looked forward to a time when Māori were not dragged through courts and into prison, but would go through a Māori justice system.

This tied in with his work on Te Tiriti: seeking Māori self-determination – a future of “constitutional transformation” where rangatiratanga was not subordinate to the Crown.

Finally, the audience reached the summit and faced the challenge of a story still being written: the view of a land in danger from climate change and human-induced threats.

Our responsibility was to stand on our maunga and make meaningful decisions about how to look after Papatūānuku, he said.

Māori nurses were in a unique position to touch each of the marker stones and leave a legacy for their people.

“Then when you stand to recite your pepeha, having touched the maunga, having walked the path, literally or figuratively to the summit, you will heed its call, and extend that call to those of our mokopuna who are yet to come.”