This article is one of two companion pieces on cultural safety in perioperative care. The other is: How to provide culturally safe care in the Aotearoa perioperative environment

I have worked as a nurse in my hospital’s perioperative department for around five years.

Coming from a very kaupapa Māori (a Māori way) upbringing and being surrounded with inspirational Māori leaders throughout my studies to become a registered nurse (RN), I had always envisioned from early on in my journey this is who I wanted to be. A Māori nurse, not just a nurse who happens to be Māori by ethnicity.

On both occasions, my concerns were not acknowledged and I was made to feel more of an annoyance.

I have faced many challenges being the only Māori nurse in my perioperative department. Some nurses are fabulous at explaining why te Tiriti is such an important document, while others have told me it is a government document but cannot understand why it is so important. At one point I was faced with racial discrimination, which opened my eyes to the lack of cultural safety knowledge and understanding among nurses.

Tikanga ‘stripped’ away

One morning in 2021 I arrived at a shift where some in-house training was about to take place. When I heard the teaching was about tūpāpaku (deceased) patient processes, something that heavily incorporates tikanga (customs and traditional values), I became worried as this was a very tapu (forbidden, taboo) subject and this was the first time I had heard about this teaching happening.

I would have expected to have had some discussion around this in-service as I had been putting together the tikanga resource folder for the department. Twice I spoke to my leaders about my concerns as I was aware that tikanga was not proficiently understood in our department. On both occasions my concerns were not acknowledged and I was made to feel more of an annoyance.

As the teaching went on, I noticed all tikanga had been stripped from the presentation.

As the presentation commenced, the first Māori word was not pronounced properly. I thought, “That is okay, she gave it a go and I know neither English nor Māori is her first language”, so acknowledged that.

As the teaching went on, I noticed all tikanga had been stripped from the presentation. There was no aroha (love/affection/empathy) incorporated in the deliverance of such a tapu process. Te reo words that were incorporated in the policy had been removed from the slides and changed to English words. Kaupapa Māori services were replaced with English services.

At the end of this in-service, I asked, “Why was tikanga not incorporated in your presentation?” I was immediately interrupted by the presenter and told that “tikanga has nothing to do with the presentation”.

As I tried to explain that the policy for this subject incorporates tikanga, I was talked over and consistently cut off in front of the department staff members present. I felt there was no point trying to explain myself as nobody could understand why this was impacting me and why I was so offended.

I felt embarrassed to be part of a workforce that did not appreciate what I bring to the department culturally.

Following the presentation, other nurses made comments like “It’s not all about Māori” and “Are you mad because you’re not on the presentation?” This was never the case nor was it the reasoning behind my questioning. I felt a duty to ensure the delivery of this presentation was tika (correct). I had to stand there and watch a teaching session that I knew was not tika.

I witnessed a sacred process getting the mana and mauri (essence) stripped from it, while also being belittled, which was the reason I was offended. I became frustrated because I had voiced my values and beliefs and was then made to look like it was just myself who had the problem.

Support for Māori patients

Around two hours later, I was approached by my charge nurse, who urgently needed me out of theatre. I handed over what I was doing and went to her. She explained, “There is a Māori patient in pre-op who needs to have a caesarean section. There has been an incident involving the patient’s partner and a staff member. The partner has left the hospital and is not allowed back and the patient is now not talking to anybody. I need you to come and talk to her because we need to get her into theatre.”

I immediately went to this young hapū māmā (pregnant woman). I went into the bed space and asked everybody to leave, then sat with her. I immediately sympathised with her, held her hand, gave her a hug, and had a brief kōrero, instantly building rapport. Within five minutes she was ready to be taken into theatre.

I became doubtful in my own practice and began to wonder if nursing was even for me.

I became her support person and I sat with her through the whole operation into recovery until she went to the ward, even though this went through my lunch break.

Her continuity of care while she was in the perioperative department was my only focus. As anaesthetists were preparing for their procedure, the allocated midwife interrupted and asked the patient, “What’s your partner’s name and how is it spelt?”

I said to the midwife, “Not right now, that is not our focus.” She continued to speak to the patient, stating that her partner will not be allowed to enter the hospital ground and security needed his name. The patient started to become frustrated, as did I. I had just spent time calming this māmā down, refocusing her mind on her baby that was about to enter this world and the midwife was compromising the progress we had just made.

I stood up and asked the midwife to leave it and go away and then I sat with this māmā, held her hand and spoke to her like “this is my sister”. I opened my heart to this māmā and cared for her and connected with her as I would my own whanaunga (blood relatives).

It has been extremely difficult to be just one Māori nurse, one Māori voice and one Māori advocate in my department.

Devalued and embarrassed

I went home extremely frustrated. I surrounded myself with my whānau where I felt supported, and I began to reflect. I quickly went from being frustrated and angry to mamae (hurt). I felt devalued, isolated, unheard and embarrassed. I felt embarrassed to be part of a workforce that did not appreciate what I bring to the department culturally.

I became doubtful in my own practice and began to wonder if nursing was even for me. I have a passion for this specialised area of nursing and I know I love the mahi (work) we do, but my wairua (spirituality), hinengaro (mental health) and mana was being affected. My very own personal Te Whare Tapa Whā (four pillars of Māori health) had been compromised.

I started reflecting on everything that had happened to me culturally since starting in this department.

Tikanga in my area meant “blue pillows for heads” (in our hospital, different coloured pillowcases differentiate pillows for the head and those for other part of the body) and “do not touch a Māori patient’s head”, but they did not understand the reasoning behind this. On another occasion, a patient asked to have a karakia (prayer) in theatre prior to the procedure (a surgical termination of pregnancy). The nurses in theatre declined, saying, “Since when do we do that? They do that in pre op, not in theatre.”

I was scared that I was going to be forced to be a nurse who just happens to be Māori.

I was shocked at this statement as these same nurses were using this karakia process in their professional development portfolios to advance in their careers, yet did not apply it to practice. This was not implementing the tikanga we have in our policy. I had to break it right down to them and then organise someone from the Māori health support team to come and do a karakia in my break as I was allocated to another floor that afternoon.

Another example I was present for was when nurses had mistaken an elderly lady for having mental health problems as she was not communicating with them in pre op. It transpired that this kuia (elderly Māori woman) only spoke fluent te reo Māori and she had an involuntary tongue movement. This was only found out when I was asked to bring the patient into theatre. She noticed I had a Māori name when I introduced myself and she proceeded to speak fluent te reo Māori to me.

Restorative hui

I raised my experiences with the perioperative nurse director, who organised a restorative hui to discuss cultural safety.

I was supported by strong Māori colleagues and leaders that I felt safe with and that uplifted and supported me. I was able to say how I felt and the impact that the series of events had on my hinengaro and my mana.

I remember being scared, scared to speak up and tell the truth out of fear that I would break the relationships I had with my colleagues or superiors in my department. I was scared that my superiors would be angry at me for drawing attention to the department and I was scared that I was going to be forced to be a nurse who just happens to be Māori.

We are not there yet, however our department has made a positive start.

The outcome from the hui was very different from what I anticipated and expected; I was heard at this hui. Changes have been made throughout my department to prevent this from happening again.

Karakia has been implemented — this is said in te reo and English at the beginning of each day. Tikanga sessions have been scheduled in the in-service calendar and my Māori resource folder is almost complete for staff to use and refer to when needed. We are not there yet, however our department has made a positive start.

From my experience, Aotearoa has a fast-growing population of international nurses and a high ratio of Māori patients. It has been extremely difficult to be just one Māori nurse, one Māori voice and one Māori advocate in my department. Cultural safety and te Tiriti are heavily incorporated in the nursing degree in Aotearoa.

I have found that Aotearoa-trained nurses understand the importance of cultural safety and know how to incorporate this in everyday practice.

Internationally-trained nurses need more assistance in understanding these prior to practising in Aotearoa to gain a better perspective of the implications this can have on our Māori nurses and the departments they work in.

A safe environment for Māori patients starts with a safe environment for Māori nurses.

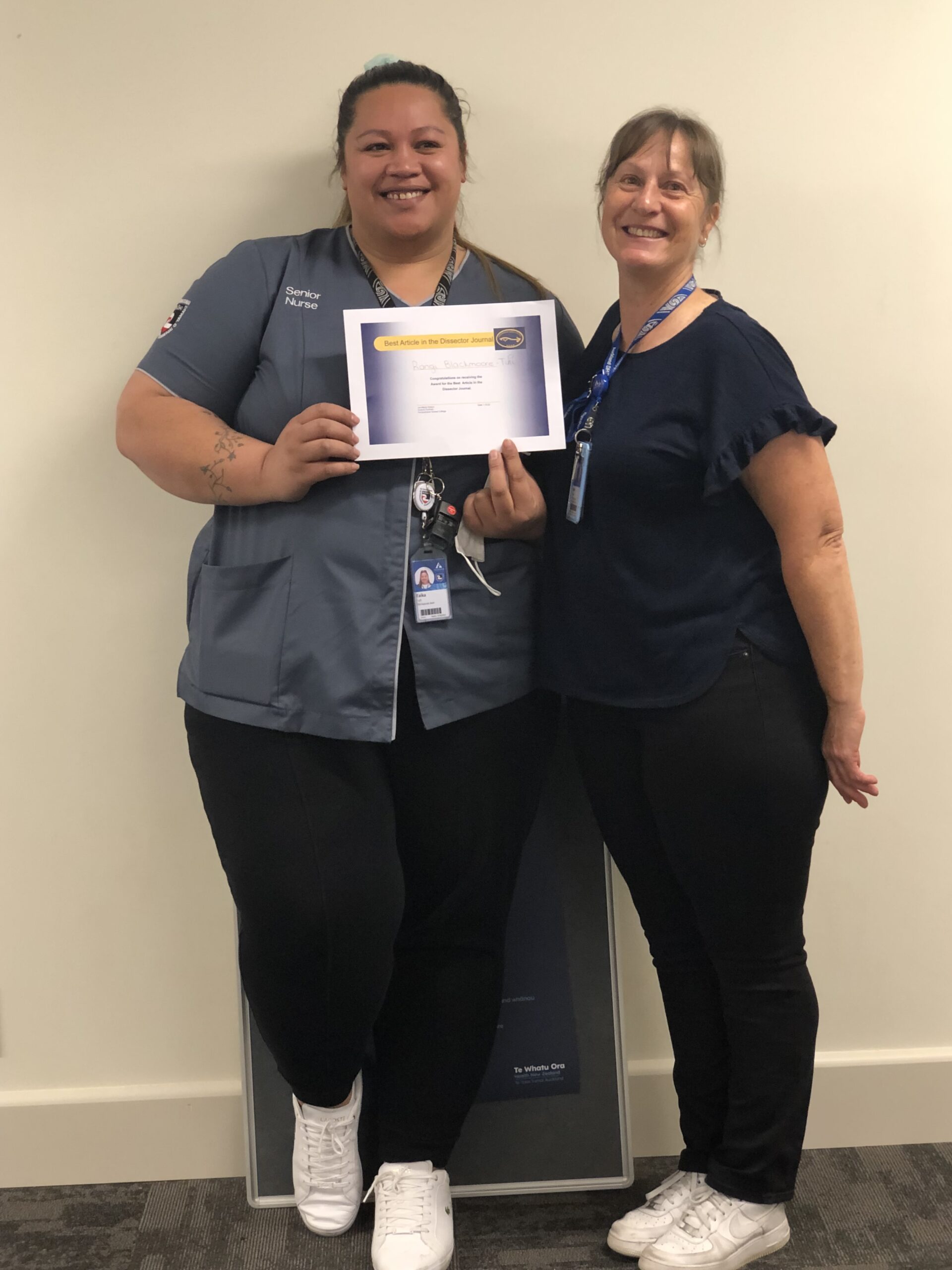

- This article was first published in the June 2022 edition of The Dissector and is reproduced here with the permission of its author and the Perioperative Nurses College (PNC) national committee. Blackmoore-Tufi’s “outstanding and brave reflection” won the PNC best article prize of $1000.

Restoration hui

By Bron Taylor

He aha te mea nui o te ao? He tāngata! He tāngata! He tāngata!

What is the most important thing in the world? It is the people! It is the people! It is the people!

Following the 2021 events outlined above, a restorative hui was called. Blackmoore-Tufi, supported by Māori colleagues, met with departmental and perioperative leaders to repair relationships. She was encouraged to share her experience, giving those around her an understanding of how deeply the events had affected her, and why. Nursing leaders listened and responded. Apologies were offered and accepted. Participants felt uplifted and relationships were restored.

Even though Blackmoore-Tufi no longer works in the department, these changes have been sustained, indelibly changing the DNA of the department.

The department’s senior nursing team carried the responsibility for delivering on the commitments made at the hui. It was agreed that these would be reviewed three weeks later to ensure progress had been made (see actions and outcomes in the table below).

Blackmoore-Tufi completed a Māori resource folder for staff to use and refer to when needed. A companion article Culturally Safe Care in the Aotearoa Perioperative Environment’ was also inspired by the hui lessons.

Blackmoore-Tufi has since progressed to a new position as clinical nurse specialist with the kaiārahi nāhi team. This team (along with the Pacific planned care navigation team) walk alongside patients on their journey to surgery, supporting them to achieve the care they deserve. This can involve speaking to patients about the hospital system or clinical aspects of their surgery and pre-operative needs.1

Even though Blackmoore-Tufi no longer works in the department, these changes have been sustained, indelibly changing the DNA of the department.

| Actions | Outcome |

|---|---|

| Rangi to have time out to recover; two weeks suggested. | Completed and returned to work |

| Apology / recant of the teaching provided on the ‘Deceased (Tūpāpaku) and referrals to the coroner for an adult, child, infant, neonate or stillbirth’ Te Toka Tumai Auckland (Te Whatu Ora) policy presentation. | Completed – well received |

| Revisit the body of work completed to implement the Tūpāpaku process. Seek a partnership approach with the Tika Rōpū in the first instance. | Completed – led by nurse consultant and fed back to Tika Rōpū |

| Operating room manager to meet with RN who gave the presentation to ensure that there is a full understanding of the cultural level of incompetence it demonstrated. Set appropriate performance objectives around competencies for a RN especially (1.2) Demonstrates the ability to apply the principles of the Treaty of Waitangi/Te Tiriti o Waitangi to nursing practice and (1.4) Promotes an environment that enables client safety, independence, quality of life, and health. | Completed – plan made regarding a programme of education – mapped inclusive of RN competency domains 1.2 &1.4 |

| Future inservice presentations to come via the Tika Rōpū to ensure tika. | Tika Rōpū happy to support |

| For the senior nurses in the department to engage and complete the resources on e-learning platform Ko Awatea intended to build knowledge in cultural safety, te Tiriti o Waitangi, our history, Māori health equity, institutional racism and self-awareness. | Ongoing |

| Design some intensive focused equity and Treaty of Waitangi/te Tiriti o Waitangi sessions to be facilitated during inservice sessions to assist the teams understanding of Te Toka Tumai strategic imperatives and commitment to equity. | Implemented |

| Implement karakia at morning huddle. | Implemented |

| Implement whakataukī /word / phrase of the week and use this during huddles and meetings. | Implemented department ‘word of the week’ email which is displayed and practised during huddles, conversations and hui |

| Other initiatives | |

| Pokakapu Ātea: Education session – cultural safety. | Commenced September 2021. Facilitated and presented by Tika Rōpū hoa mahi |

Note: Āhua Tohu Pōkangia Tika Rōpū is an advisory group consisting of members seconded as required. Their purpose is to advise senior leadership in Perioperative Services on:

- How to best achieve equity within Āhua Tohu Pōkangia | Perioperative Services.

- How to deliver our responsibilities enshrined in Te Tiriti o Waitangi.

- How to progress and deliver change that moves the directorate towards a workforce whose diversity represents the population of Te Toka Tumai.

- How to embrace Māori culture and tikanga and embed it in our service delivery.2

References

- Te Toka Tumai. (n.d.a). Equity focused planned care for Maori and Pacific patients.

- Te Toka Tumai. (n.d.b). Tika Āhua Tohu Pōkangia — Equity in Perioperative Services.