Clinical research has recently brought the subject of resilience — a complex and often neglected aspect of patient care — into the spotlight. The focus of this interest lies in exploring the complexity of the human response to the challenges of ill-health, to explain why some individuals are better able to cope with adversity than others.

The concept of resilience has particular relevance for patients in palliative care, who are confronting their own mortality and the intense loss which accompanies a life-limiting illness. Resilience offers a means of protection, particularly against the negative impact of stress, at the same time supporting an individual’s adjustment to their end-of-life care.1, 2

Fostering resilience requires a comprehensive understanding of the specific factors that underpin a person’s innate capacity to cope and the unique combination with which each patient presents. This helps to identify those who may need additional support and enables practitioners to tailor aromatherapy interventions specific to the patient’s individual strengths and needs.

Definitions of resilience

In his powerful memoir of life in Auschwitz, Viktor Frankl wrote, “When we are no longer able to change a situation, we are challenged to change ourselves.”3 In the worst imaginable circumstances, his firm belief was that the human spirit can rise above any given situation. These early and striking observations of resilience are human realities which are difficult to define.

The concept of resilience has since continued to evolve with the focus of research extending beyond the individual to other areas of human experience. This includes palliative care, where a broader outlook considers the patient, their families, staff, organisations and communities. For definitions specific to these areas, readers are referred to the exceptional collection of writing in Resilience in Palliative Care.4

Resilience can be considered as an individual’s ability to maintain or restore relatively stable psychological and physical functioning when confronted with stressful life events and adversity.5 This view aligns with the holistic nature of palliative care.

Resilience in the context of cancer

Resilience has predominantly been evaluated in patients receiving active forms of cancer treatment and survivors of cancer. Optimism, hope and early coping were identified as critical elements of resilience in a systematic review published in 2014.1

Opportunities for personal growth and improved quality of life were evident in many who overcame cancer and its treatment. Importantly, the authors highlight that adversity presents itself across the entire cancer trajectory with each stage generating its own unique set of stressful challenges.

Optimism, hope and early coping were identified as critical elements of resilience.

However, not everyone reacts to adversity in the same way, raising questions as to whether clinical differences exist in how resilience manifests across the cancer spectrum and whether interventions to foster resilience need to be adjusted at each stage.

A recent large-scale review2 examined factors which promote resilience and post-traumatic growth in patients across the cancer trajectory. Currently, limited evidence is available to support a reliable relationship between socio-demographic factors and resilience in patients with cancer, in addition to disease-related variables such as the time since diagnosis and the severity of the disease itself.

However, strong associations were identified in four common areas, as shown in Table 1.

| Table 1: Common factors underpinning resilience in patients with cancer2 |

|---|

|

|

|

|

Personality traits

Anecdotal evidence has long supported the relationship of positive personality traits with resilience in patients facing life-threatening illness. Research-based findings have been more specific, identifying optimism, self-esteem, positive emotions and personal control as being central to an individual’s resilience.2

Integral to positivity is laughter and the expression of positive emotions, including gratitude, interest and love, all of which have been shown to increase levels of resilience and improve quality of life.6, 7 Predominantly, this has been evaluated around the time of diagnosis or during cancer treatment.

Social circumstances

Supportive, meaningful relationships, where an individual feels loved, valued and esteemed, are considered strong determinants of resilience. Specifically important are sustainable relationships,2 which enable patients to share and process their cancer-related experiences. These are an important means of support when adjusting to each stage of the cancer trajectory.

Patients with this level of social support generally report higher levels of resilience and lower levels of distress.8

Positive coping strategies

A critical element of resilience is the ability to employ coping strategies focused on problem-solving. Self-determination to overcome difficulties, self-efficacy, flexibility in adapting to change, positive reappraisal and social interaction are among several strategies used, where patients report less distress and experience improved quality of life.2, 9

Optimism, hope and spirituality

In patients with cancer, optimism is consistently associated with better adjustment to the disease itself, an improved sense of wellbeing and reduced distress, and is positively linked to resilience and hope.2 Strategies which tackle spiritual distress by fostering hope are also central to building resilience in this patient group.

Hope is considered a flexible experience which changes over time and is influenced by personality, relationships and social support.10

Resilience in the context of life-limiting illness

Few studies have evaluated resilience in those with advanced-stage disease. For the patient group who meet entry criteria to be included in systematic reviews, high levels of social and psychological support, combined with optimism, hope and spirituality, are central to increased levels of resilience.1, 2

Although resilience is under-researched in patients with life-limiting illness, parallels can be drawn with studies evaluating quality of life in these patients. A systematic review of qualitative data identified a broad range of domains which patients consider important to their quality of life.11 These are summarised in Table 2, below.

Spiritual aspects were identified in all but one of the studies which met the robust selection criteria (n=24), closely followed by social and physical domains. When compared with Table 1, several similar threads exist. Therefore, it seems reasonable that fostering resilience in patients with life-limiting illness has the potential to positively influence several important aspects of their quality of life.

| Table 2: Patient-reported aspects important to their quality of life11 | |

|---|---|

| Aspect | Examples |

| Cognitive aspects |

|

| Emotional aspects |

|

| Aspects of health care |

|

| Aspects of personal autonomy |

|

| Physical aspects |

|

| Preparatory aspects |

|

| Social aspects |

|

| Spiritual aspects |

|

The holistic nature of resilience

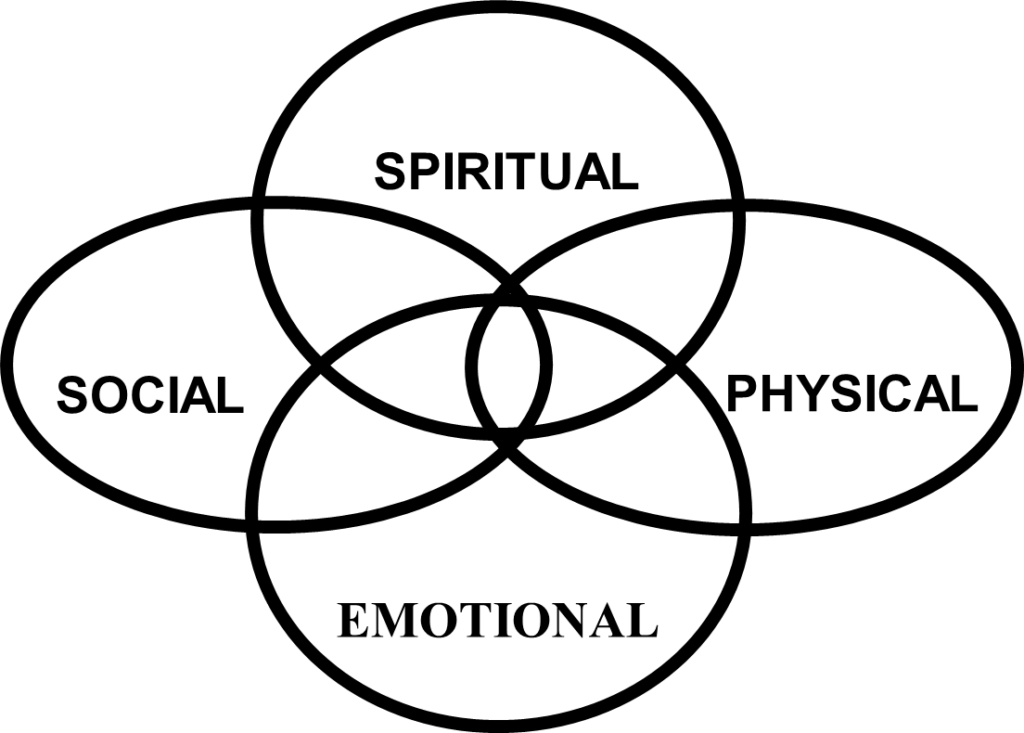

Resilience is a complex concept, largely defined by the interplay of several factors, as summarised in Tables 1 and 2. These factors align with the holistic care model where an individual is considered an integrated whole, comprising physical, psychological, social and spiritual dimensions (see Figure 1, below). Each patient presents with a unique combination of these dimensions, relevant to their individual circumstances.

Figure 1: The holistic care model

Although the holistic care model is integral to the philosophies of several health disciplines, including palliative care, the deeply embedded root of the biomedical model often reduces the focus of care to the physical element. Specifically, this means the diagnosis of disease and the physical aspects of symptoms and their management.

Consequently, insufficient attention is given to a patient’s social, emotional and spiritual dimensions and their inter-connectedness.12

This is increasingly evident in patients with life-limiting illness, where studies evaluating psychological and spiritual aspects of care identified these symptoms as being frequently under-recognised by health-care professionals and consequently undertreated.13, 14, 15, 16, 17 This is likely to have a negative impact on a patient’s level of resilience and quality of life.

The potential of aromatherapy

Interventions which foster resilience generally target spiritual and psychosocial distress. These areas are recognised aspects of successful aromatherapy intervention which are explored in chapters 5 and 6 of my book Integrating Clinical Aromatherapy in Palliative Care.18

Spiritual distress does not manifest as a set of pre-determined symptoms, rather a variety of expressions of distress which are unique to each patient. For some patients, it may influence how they experience and express the physical symptoms of their disease, particularly pain. For others, spiritual distress may cause greater concern than their physical symptoms.

A review of qualitative research found fear, insecurity and nervousness as predominant manifestations of spiritual distress.19 Associated increases in anxiety, depression, panic attacks, uncertainty and fear of the unknown were also reported. Spiritual suffering can be expressed through questioning the meaning of life, anger with God, or viewing illness as a punishment for life choices.20 Additionally, feelings of guilt, shame or an inability to trust oneself, other people or God/higher being, can result in a lack of inner peace.21

Aromatherapy can help alleviate such distress by working with essential oils with properties that calm the central nervous system. With careful selection, these can be administered via aromatherapy inhalation sticks, rollerball applicators, aroma patches and aroma showers, as well as via skin absorption using appropriately diluted oils for relaxation massage, aromatic baths and footbaths.

Understanding the factors which underpin resilience (see Table 1) helps to identify patients in need of additional support and tailor interventions to address their unique capacities. The following case study demonstrates the beneficial effects of integrating clinical aromatherapy alongside conventional medical interventions.

CASE STUDY: Winnie’s experience

Referral

Winnie presented to the specialist palliative care team with rapidly deteriorating health, with a complex range of symptoms arising from advanced cancer of unconfirmed sources. Clinical concern about her ingestion of essential oils prompted an aromatherapy referral by the nursing team to ensure safe integration with prescribed pharmacology.

Background

Throughout her life, this independent, erudite 69-year-old lady had used plant-based medicine to maintain her health and wellbeing. Although taking prescribed opioids for pain relief and anti-emetics for nausea, she preferred to use natural medicine alongside her conventional regime. She felt overly drowsy with prescribed pharmacology, particularly anti-emetics, which she had stopped taking because she felt it was easier to cope with persistent nausea than intense drowsiness.

Winnie was self-medicating by taking essential oils orally. Unfortunately, this was not based on the professional advice of a qualified aromatherapist and involved:

- Boswellia carterii (frankincense): 2 drops undiluted, sublingually (under the tongue) 3x daily

- Copaifera officinalis (copaiba balsam): 2 drops undiluted, sublingually 3x daily

Personal goals

Having experienced a complex pathway through the health-care system, Winnie’s priorities were:

- To be involved in all treatment decisions

- To continue self-administration of essential oils

- To live as well and independently as she could in the life she had left

- To see her new grandchild, due to be born in a few months

Aromatherapy intervention

Many of the extended family were present at the first home visit and space was limited. Winnie was weak with fatigue, and largely confined to one room due to the limitations of her breathlessness, for which she required supplemental oxygen. Her oral mucosa was red and dry but intact.

We discussed her current ingestion of essential oils, which had been ongoing for several weeks, with no alleviation of her symptoms and further deterioration in her health noted.

Winnie described a spiritual and cultural connection with Boswellia carterii (frankincense) and enjoyed the aroma of the Copaifera officinalis (copaiba balsam). As such, it was suggested that she continue using both essential oils but change the route of application from sublingual to topical use (ie on the skin).

We considered other essential oils and base substances, with analgesic and anti-inflammatory properties, more suited to her current pain from the right kidney.

Mindful of her deteriorating renal function, we proposed a topical pain-relief blend starting at a concentration of 3 per cent, plus an aromatherapy inhaler stick formulated with her choice of essential oils from a selection designed to alleviate nausea (see Table 3, below).

Winnie was willing to try this combination and agreed to stop taking the essential oils orally.

| Table 3: Winnie’s aromatherapy interventions | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Method of application | Botanical products Botanical name (common name) |

Amount used | Directions for use |

| Topical blend ‘Pain relief’ 3% |

Boswellia carterii (frankincense) Copaifera officinalis (copaiba balsam) Kunzea ambigua (kunzea) Lavandula latifolia (spike lavender) Zingiber cassumunar (plai) |

10% 25% 30% 25% 10% |

Patient-assisted Apply THREE times daily After 1 week, review |

| Calophyllum inophyllum (tamanu) Simmondsia chinensis (jojoba) |

40%

60% |

||

| Aromatherapy inhaler stick ‘Nausea relief’ |

Lavandula angustifolia (lavender true) Citrus bergamia (bergamot) Zingiber officinalis CO2 — total extract (ginger CO2) Simmondsia chinensis (jojoba) |

4 drops 5 drops 4 drops 1ml |

Patient-directed as required At each use, inhale 4-8 breath cycles |

Within 24 hours, the clinical team reported that Winnie was less restless at night, with an associated reduction in pain intensity. One week later, at the next home visit, she described how she was sleeping through the night, she no longer required supplemental oxygen and the nausea was easing.

By the third visit, again one week later, her breathlessness had totally resolved and the nausea was well-controlled with regular use of the aromatherapy inhaler stick. Her pain level had significantly reduced to the extent she had completely stopped her prescribed opioids. However, fatigue remained a persistent issue which we explored.

Winnie spoke of the exhaustion she felt from no longer being independent. This was not how she had lived her life. Conversations ensued between the multi-disciplinary team (MDT) and her close family members to determine how she could achieve her goal of living more independently.

Her pain level had significantly reduced to the extent she had completely stopped her prescribed opioids.

With improved physical symptoms, the support of a daily carer and the clinical team available via a 24-hour on-call service, Winnie was quickly able to return to independent living.

At the next aromatherapy follow-up, she attended the hospice day centre. She described how she had returned to her normal diet, was feeling physically stronger, less fatigued and sleeping well. This resulted in a further decrease in her level of pain intensity, with an associated self-reduction in the pain-relief blend to twice daily applications.

Reflection

From a patient’s perspective, personal autonomy is a central aspect of palliative care.11 In this case, autonomy was achieved by supporting Winnie’s decision to integrate natural medicine within her end-of-life care and involve her in all essential oil choices and intervention options.

Central to the success of this approach is the cohesive nature of the MDT. Recognising and utilising the strengths of each discipline, together with timely intervention, provided a structure of holistic support for this lady.

This, in turn, fostered her resilience to the extent that she was able to return to independent living with a restored degree of “normalcy” in the life she had left. Winnie was also able to welcome her second grandchild into the world.

In Winnie’s words: “The most important part is being listened to and being heard. It’s about being supported in how I want to do things. The positivity this [hospice] team brings is allowing me to do that and to live my life well.”

Acknowledgement

This is an abridged version of the chapter, “Fostering resilience in patients with life-limiting illness” taken from Carol Rose’s book, Integrating Clinical Aromatherapy in Palliative Care, published in 2023 by Singing Dragon. She can be contacted at [email protected]

Carol Rose, RN, BSc(hons) palliative nursing, Dip Aroma, registered massage therapist, is an RN, clinical aromatherapist, educator and author. She works as an RN in specialist palliative care, North Haven Hospice, Whangarei.

References

- Molina, Y., Yi, J., Martinez-Gutierrez, J., Reding, K., Yi-Frazier, J., & Rosenberg, A. (2014). Resilience among patients across the cancer continuum: diverse perspectives. Clinical Journal of Oncological Nursing, 18(1), 93-101.

- Seiler, A., & Jenewein, J. (2019). Resilience in cancer patients. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 10(208), 1-31.

- Frankl, V. (1984). Man’s Search for Meaning: An Introduction to Logotherapy. Simon and Schuster. (Original work published in 1946).

- Monroe, B., & Oliviere, D. (2009). Resilience in Palliative Care – achievement in adversity (2nd ed). Oxford University Press Inc.

- Bonanno, G., Westphal, M., & Mancini, A. (2011). Resilience to loss and potential trauma. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 7, 511-535.

- Manne, S., Myers-Virtue, S., Kashy, D., Ozga, M., Kissane, D., Heckman, C., Rubin, S., & Rosenblum, N. (2015). Resilience, positive coping, and quality of life among women newly diagnosed with gynaecological cancers. Cancer Nursing, 38(5), 375-82.

- Tugade, M., Fredrickson, B., & Barrett, L. (2004). Psychological resilience and positive emotional granularity: examining the benefits of positive emotions on coping and health. Journal of Personality, 72(6), 1161-90.

- Somasundaram, R., & Devamani, K. (2016). A comparative study on resilience, perceived social support and hopelessness among cancer patients treated with curative and palliative care. Indian Journal of Palliative Care, 22(2), 135-40.

- Eicher, M., Matzka, M., Dubey, C., & White, K. (2015). Resilience in adult cancer care: an integrative literature review. Oncology Nursing Forum, 42(1,) E3-16.

- Li, M., Yang, Y., Liu, L., & Wang, L. (2016). Effects of social support, hope and resilience on quality of life among Chinese bladder cancer patients: a cross-sectional study. Health Quality of Life Outcomes, 14, 73.

- McCaffrey, N., Bradley, S., Ratcliffe, J., & Currow, D. (2016). What aspects of quality of life are important from palliative care patients’ perspectives? Journal of Pain & Symptom Management, 52(2), 318-328.

- Youngson, R. (2012). Time to Care. Rebelheart Publishers.

- Austen, P., Macleod, R., Siddall, P., McSherry, W., & Egan, R. (2016). The ability of hospital staff to recognise and meet patients’ spiritual needs: a pilot study. Journal for the Study of Spirituality, 6(1), 20-37.

- Balboni, T., Paulk, M., Balboni, M., Phelps, A., Loggers, E., Wright, E., Block, S., Lewis, E., Peteet, J., & Prigerson, H. (2009). Provision of spiritual care to patients with advanced cancer: associations with medical care and quality of life near death. American Society of Clinical Oncology, 28(3), 445-452.

- Edwards, A., Pang, N., Shiu, V., & Chan, C. (2010). The understanding of spirituality and the potential role of spiritual care in end-of-life and palliative care: a meta-study of qualitative research. Palliative Medicine, 24(8), 1-18.

- Epstein-Peterson, Z., Sullivan, A., Enzinger, A., Trevino, K., Zollfrank, A., Balboni, M., VanderWeele, T., & Balboni, T. (2015). Examining forms of spiritual care provided in the advanced cancer setting. American Journal of Hospital Palliative Care, 32(7), 750-757.

- O’Connor, M., White, K., Kristjanson, L., Cousins, K., & Wilkes, L. (2010). The prevalence of anxiety and depression in palliative care patients with cancer in Western Australia and New South Wales. Medical Journal of Australia, 193(5), S44-47.

- Rose, C. (2023). Integrating Clinical Aromatherapy in Palliative Care. Singing Dragon.

- Edwards, A., Pang, N., Shiu, V., & Chan, C. (2010). The understanding of spirituality and the potential role of spiritual care in end-of-life and palliative care: a meta-study of qualitative research. Palliative Medicine, 24(8), 1-18.

- Richardson, P. (2014). Spirituality, religion and palliative care. Annals of Palliative Medicine, 3(3), 150-159.

- Speck, P. (2011). Spiritual/religious issues in care of the dying. In J. Ellershaw and S. Wilkinson (eds) Care of the Dying: A pathway to excellence. Oxford University Press.