Key points

- About 30,000 people live with chronic hepatitis C in Aotearoa, and up to 40 per cent are unaware they have it.

- Early detection and treatment can prevent serious liver damage and significantly increase life expectancy.

- Oral antivirals are well-tolerated and can provide almost a 100 per cent cure rate.

- Raising awareness and reducing stigma will help to identify people for treatment.

- “The face of hep C” may not be who you think it is — it only takes one exposure incident to contract the virus.

- Regional support is readily accessible to health providers and a comprehensive national HealthPathway is in place.

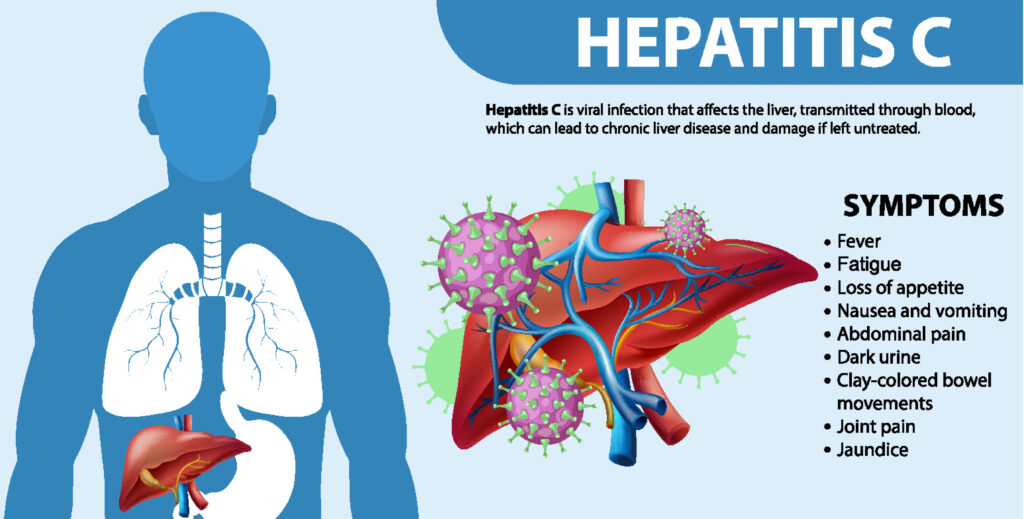

Hepatitis C is inflammation of the liver caused by the blood-borne hepatitis C virus (HCV). An acute illness can occur at the time of infection but, more often than not, the infection is asymptomatic and often goes unnoticed.

For acute illness with symptoms, even these are generally mild, non-specific and can present weeks or up to six months after exposure. Approximately 30 per cent of infected individuals spontaneously clear the virus within six months without treatment. This is often the case for people who present with an acute illness.

The remainder develop chronic HCV infection, which carries a 15-30 per cent risk of developing cirrhosis of the liver within 20 years.1

Early detection and cure is estimated to improve life expectancy by almost 20 years.

Early detection and cure of HCV infection, using effective short-course oral treatment, is now possible and can prevent serious liver damage, liver failure, hepatocellular carcinoma and further transmission, as well as improve long-term health.1 Early detection and cure is estimated to improve life expectancy by almost 20 years.2

The World Health Organization has set a target to eliminate viral hepatitis as a major public health threat by 2030 by achieving a 90 per cent reduction in new chronic infections and a 65 per cent reduction in mortality, compared with 2015 levels.3

Recognising this unique opportunity, in 2021 the Ministry of Health – Manatū Hauora released its National Hepatitis C Action Plan for Aotearoa New Zealand – Māhere Mahi mō te Ate Kakā C 2020-2030. It includes a framework for achieving improved, equitable health outcomes for all New Zealanders living with hepatitis C, while also advancing the health aspirations of Māori, who are disproportionately affected.4

The health burden of hepatitis C

By 2040, it is projected that viral hepatitis will kill more people worldwide than tuberculosis, malaria and HIV combined.5 In Aotearoa, chronic hepatitis C is the leading indication for liver transplantation and is responsible for more than 200 deaths annually – all of them preventable with earlier diagnosis and treatment.4

By 2040, it is projected that viral hepatitis will kill more people worldwide than tuberculosis, malaria and HIV combined.5 In Aotearoa, chronic hepatitis C is the leading indication for liver transplantation and is responsible for more than 200 deaths annually – all of them preventable with earlier diagnosis and treatment.4

Approximately 30,000 people are living with chronic hepatitis C in Aotearoa.6 Between 35 and 40 per cent are undiagnosed due to lack of awareness of previous exposure risk and lack of symptoms, the prevailing stigma about having hepatitis C (creating a reluctance to test), and outdated knowledge about management and treatment options and success rates.4

Overall, Māori are considered to be at higher risk of hepatitis C and its long-term complications, compared with other population groups.4

About 1000 new cases of chronic hepatitis C are recorded each year,6 with many of these people having been infectious for years but unaware.

Overall, Māori are considered to be at higher risk of hepatitis C and its long-term complications, compared with other population groups.

We need to treat at least 2200 individuals per year to achieve our goal of eliminating hepatitis C by 2030.7,8 However, for a range of reasons, largely due to lack of new diagnoses, treatment uptakes have fallen from more than 500 per month in 2019 to 26–57 per month for the first nine months of 2023.9

The peak incidence of HCV infection was during the 1960s to 1980s, secondary to the rise in people who inject drugs (PWID). Today, the incidence is declining but the main risk factor remains injecting drug use.4

In Aotearoa, the risk of infection with HCV falls primarily into specific categories:10

- History of injecting drug use (>99 per cent of new infections).

- Recipients of blood products or organ donation in New Zealand before 1992.

- People who have been imprisoned.

- Immigrants from regions with high HCV prevalence1 (the largest numbers of HCV-positive immigrants to New Zealand are from the Indian subcontinent, largely northern India and Pakistan, and from Egypt, and Russia and Eastern Europe).

- History of tattoos or body piercings with suboptimal infection control.

- Contacts of HCV-infected persons (eg sharing needles or razors).

- Recipients of medical or dental treatments, including vaccination, in a high-prevalence region where equipment may not have been sterile.

- People living with HIV (particularly men who have sex with men living with HIV).

- Birth to a mother with HCV – low risk (5 per cent) of transmission.

New treatment makes elimination possible

Effective treatment of HCV infection using direct-acting antivirals (DAAs) puts the goal to eliminate the virus within reach. The latest DAA, a fully funded combination of glecaprevir 100mg and pibrentasvir 40mg (Maviret), has been available since 201911 and has significant advantages over earlier treatments:

- A 98 per cent cure rate, defined as HCV not present in the blood at three months after treatment ends (in patients who complete the full course, the cure rate is 99.5 per cent).

- Effective against HCV genotypes 1 to 6 (so genotype testing is not required).

- Easy (oral) administration: three tablets, once-daily with food for eight weeks (12 or 16 weeks for some previously treated patients).

- Adverse effects are generally mild (eg nausea, headache).

- Few contraindications and – while lifestyle advice would recommend stopping – alcohol and illicit drug use are not contraindicated (a potential barrier to treatment in the past).

- Accessible in primary health care, with many providers not charging consultation fees.

Prescribers should refer to the New Zealand Formulary,12 product data sheet,13 manufacturer information14 and Community HealthPathways for full prescribing details and treatment recommendations. Maviret is a special access medicine, meaning only contracted pharmacies can dispense it.15

New Zealand Action Plan

When DAAs for hepatitis C became available, treatment uptake was high. This was partially due to the large number of people already diagnosed with hepatitis C who chose to await for the new medicine rather than use the previously available treatment, injectable interferon. A subsequent decline in treatment levels followed, reflecting a lack of new diagnoses.8

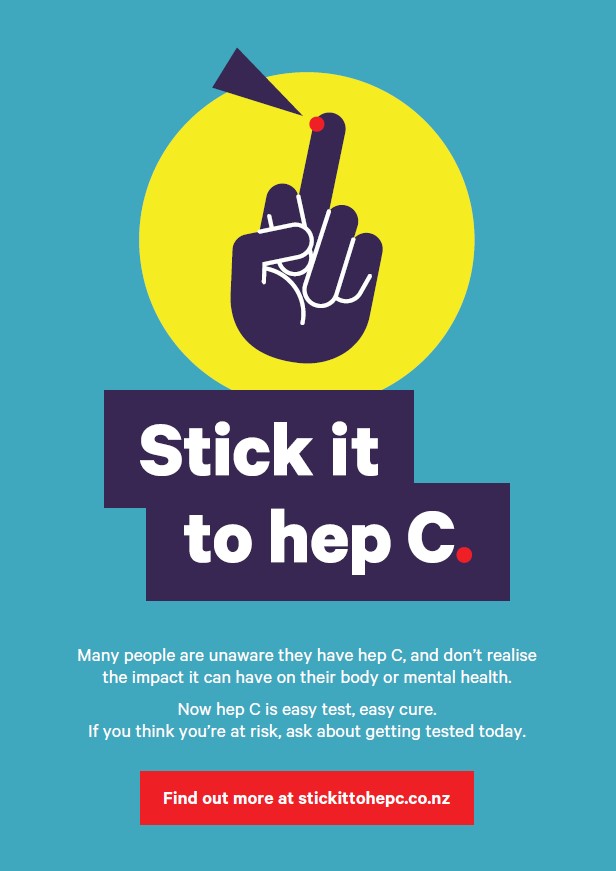

In 2022, Te Whatu Ora funded Stick It To Hep C, a successful campaign to increase public awareness, encourage people to act by seeking more information or getting tested, and to make it clear that hepatitis C could be cured.

The main challenges now are continuing to promote testing and the easily accessible oral treatment leading to cure, identifying and engaging with people at high risk of hepatitis C (many remain unaware of their risk), overcoming stigma, and providing acceptable education and support for accessing and completing treatment.

To reduce the chronic hepatitis C burden, the New Zealand Action Plan3 overview identifies the need to focus on:

- awareness and understanding

- prevention and harm reduction

- testing and screening

- surveillance and monitoring

- integration and access to care.

Key priorities are to target populations known to have a higher prevalence of hepatitis C and also the long-term complications of chronic infection.4

Given the effective cure rate provided by current treatment, there is support for a pilot study to evaluate testing of the general population.4 Universal testing occurs in some countries but to be practical in Aotearoa it needs to be linked to a registry, which has yet to be developed.8

Testing patients without risk factors for HCV infection is not recommended at this time.16,17 However, testing patients with unexplained elevations of the liver enzyme alanine aminotransferase beyond three months is essential.

Anyone with a history of intravenous drug use, even with normal liver function tests, requires HCV antibody serology then a confirmatory HCV RNA (PCR) test

Active case finding within prisons and drug dependency clinics, and laboratory lookback programmes to identify people with chronic HCV infection and no record of treatment, are other targeted screening approaches being employed.18

There is also a regional service where community providers screen and offer testing and links to care.19

Testing for HCV infection

Screening (non-diagnostic) test for HCV antibodies

Venepuncture at a community lab or finger-prick point-of-care serology to test for HCV exposure.

- A negative antibody test indicates no HCV infection, unless the patient is immunosuppressed or has an acute HCV infection (antibodies may take up to six months to develop*).

- A positive antibody test indicates a current or previous HCV infection.

* Consider the possibility of acute infection without antibody development in individuals with a known risk of HCV exposure, and explain why continued antibody testing may be useful.

Confirmatory (diagnostic) test for HCV RNA is required of all positive antibody testsǂ

Venepuncture at a community lab, or finger-prick for a “dried blood spot” test (collected in community settings and sent to a lab that performs the PCR assay for HCV RNA. Dried blood spot testing is being set up at Auckland City Hospital’s LabPLUS and Wellington Hospital).

- A negative HCV RNA test indicates the person is not currently infected and does not require treatment. (Repeat after three months to confirm the negative result).

- A positive HCV RNA test result confirms chronic HCV infection.

ǂ Some laboratories perform HCV core antigen assays rather than HCV RNA assays -– both are appropriate tests for detecting current HCV infection.

ǂ HCV RNA testing may be requested as a reflex test on blood taken for HCV antibody serology at a community lab, so patients do not require another blood draw. In some regions, it is performed automatically.

Confirmation-of-cure testing

For patients completing treatment with Maviret, a sustained virological response (SVR) test to confirm viral clearance is required at four weeks (minimum) after treatment ends.

Patient assessment and treatment in primary care

A person with hepatitis C confirmed by HCV RNA assay can receive treatment with Maviret once cirrhosis or complicating factors have been excluded with:16

- clinical examination for symptoms and signs

- laboratory tests for liver disease, hepatitis B, HIV (for those at risk of HIV) and pregnancy

- non-invasive liver assessment: APRI (AST-to-platelet ratio index, see below) calculation or liver elastography (FibroScan), if available

- check for medicines interactions: New Zealand Formulary interactions checker or University of Liverpool HCV medicines interactions checker.

APRI score

- If APRI is <1.0, the patient does not have cirrhosis and can be treated with Maviret for eight weeks.

- If APRI is ≥ 1.0, the patient has a 50 per cent chance of having cirrhosis and should be referred for a FibroScan for confirmation. FibroScans require secondary referral but are becoming increasingly accessible in the community through regional hepatitis C outreach services.

If cirrhosis cannot be excluded, discussion with a gastroenterologist or referral to secondary care is recommended. Likewise, for patients previously unsuccessfully treated with other hepatitis C medicines, who may require treatment with Maviret for longer than the standard eight weeks.

Additional sofosbuvir-based regimens, eg Harvoni (ledipasvir and sofosbuvir20), which can only be accessed through the HCV retreatment study at the New Zealand Liver Transplant Unit, are also used for people who remain HCV RNA positive after Maviret treatment.

Uncertain liver pathology results, an eGFR <30ml/min/1.73m2, or hepatitis B or HIV co-infection should also prompt discussion with a specialist.

After four weeks of treatment with Maviret, a patient follow-up to check for adverse drug effects is recommended. This is also an important opportunity to encourage treatment adherence for the full course, increasing the chance of cure and helping avoid treatment resistance. The one to two per cent of patients who fail to clear HCV require specialist referral.16

Repeat liver function tests can be done at the same time as the test of cure (a minimum of four weeks after treatment ends) and again at 12 weeks post-treatment as they may take longer to normalise. Annual HCV RNA diagnostic tests are recommended for people with ongoing risk factors (eg, PWID) as previous infection does not confer immunity.

Note that HCV antibodies will remain positive for life once a person has been exposed to the virus, so repeating the antibody test will not be helpful in determining re-infection.16,18

Initiatives to increase testing and treatment uptake

It is not possible to treat patients if they cannot be identified. Supportive information and resources need to be made highly visible; displaying posters in waiting areas is an effective tool. Providing patients with written information on risk factors and the availability of curative treatment may prompt a future discussion or the direct uptake of point-of-care testing.

. . . some people diagnosed with hepatitis C have no firm knowledge of how it was contracted, and there is no need to feel stigma or shame.

When discussing HCV risk or testing, it is useful to point out that some people diagnosed with hepatitis C have no firm knowledge of how it was contracted, and there is no need to feel stigma or shame.

Point-of-care finger-prick antibody testing for HCV is widely available. The “Stick It To Hep C” promotional campaign includes a website with regional testing providers: GPs, pharmacies, kaupapa Māori health providers and needle exchanges.

It also has FAQs on hepatitis C, testing and treatment. Results of whether a person has ever been exposed to HCV are confidential (“no questions asked”) and available within minutes after a finger-prick test.

Te Whatu Ora funds the delivery of hepatitis C assessment and treatment services in an integrated approach across four regions to support primary care, each region with its own coordinator.19 A mix of initiatives are employed, including:

- community clinics and free mobile services run by specialist nurses — to reduce disparity and geographical disadvantage and provide a “one-stop shop” as much as possible

- engaging with previously diagnosed patients with no record of treatment, through the Pharmac laboratory lookback programme

- organising FibroScan clinics in the community, hospitals and correctional facilities (without a specialist appointment)

- testing clinics in needle exchanges and coordinating with community alcohol and drug services, and opioid substitution treatment services

- point-of-care PCR testing (Cepheid GeneXpert; only available in some regions).

There are regional variations in how HCV point-of-care testing is supported but each follows a documented process approved by the Hepatitis C Implementation Advisory Group and its chair, Professor Ed Gane, a liver transplant specialist based at Te Toka Tumai Auckland.21 Finger-prick HCV antibody serology testing in the pharmacy or outreach service is supported by the community hepatitis C service, specialist nurses and the patient’s GP.

Training and assessment are proposed in 2024 for selected nurses and pharmacists to become accredited providers of glecaprevir and pibrentasvir for hepatitis C, without prescription.

Increased access to Maviret through exemption to prescription status for pharmacists and nurses with appropriate knowledge and experience22 is in the final stages of planning. Training and assessment are proposed in 2024 for selected nurses and pharmacists to become accredited providers of glecaprevir and pibrentasvir for hepatitis C, without prescription. The two medicines have already been reclassified for this purpose.23

This is expected to be useful for accredited nurses and pharmacists who also perform point-of-care HCV antibody testing, so an individual is not lost to follow-up after a positive test, and, when people who were lost to follow-up present, a supply of medication can be provided on the spot.

To improve access to hepatitis C treatment in the community, in addition to low-cost access for community services card (CSC) holders, people seeking treatment from their GP who would qualify for a CSC may be eligible for a special needs grant to cover the costs of transport and up to three or four doctor visits.

This may include people recently released from prison who have already started hepatitis C treatment.24

Conversations to overcome barriers

Before any of this can happen, there needs to be a level of education or a conversation that reassures a person that testing is something they should proceed with. There also needs to be communication with the wider population to reduce stigma and prompt a realisation that “the face of hep C” may not be who you think it is.

It is useful to emphasise that HCV is highly infectious and spreads when infected blood from someone with hepatitis C comes into contact with another person’s blood, and that HCV can survive outside the body for days, even in tiny and unseen traces of dry blood.

Gaining the patient’s trust and being non-judgmental are equally important. People with hepatitis C come from all walks of life.

Injecting drug use is the main route of infection but people need to know there are many other ways to contract the virus, and it only takes one exposure incident. When symptoms do emerge, it could be 20 or 30 years after the acute infection, and the risky behaviour leading to infection may have been a single occurrence, long forgotten.

Gaining the patient’s trust and being non-judgmental are equally important. People with hepatitis C come from all walks of life. As a health-care professional, you can reassure the person that you do not need to know “how” they might have been exposed.

Having posters and written information in waiting areas allows the person to go away and digest the information and consider returning for testing (see resources section below).

Opportunistic testing is important while population-wide testing is some way off. A casual introduction of the subject can sometimes sidestep the implicit stigma: “While you’re here for xyz, we are doing free hepatitis C testing. It’s curable now with a course of tablets -– have a quick read of this and let me know if it’s possible you’ve ever been exposed to the hepatitis C virus.”

The person does not need to state how they consider themselves at risk.

Specific factors alerting a possible need for testing may be evident in a person’s medical notes, eg references to health care while in prison, or immigration from or residence in a high-risk country, especially if combined with medical or dental procedures or other risk factors.

Some patients may even have had a positive diagnostic test for HCV but declined previously available treatments, been ineligible for funded treatment (due to genotype) or the treatment may have been unsuccessful or not completed.

Visit your local Community HealthPathways for further treatment recommendations.

Resources

For health professionals:

- AbbVie Care pharmacy locator

- He Ako Hiringa website: Legendary Conversations podcast episode 7

- Ministry of Health Manatū Hauora website: National Hepatitis C Action Plan for Aotearoa New Zealand — Māhere Mahi mō te Ate Kakā C – read online or download the PDF

- New Zealand Needle Exchange Programme

- Te Whatu Ora Health New Zealand website: Regionally led integrated approach to the delivery of hepatitis C services. Includes contact details of the regional hepatitis C coordinators.

To provide to patients:

- Healthify He Puna Waiora website: Hepatitis C Pokenga huaketo – Q&A, short videos, free brochures and help lines

- Hepatitis C website with information for patients and a downloadable risk checklist

- Ministry of Health Manatū Hauora website: Hepatitis C

- New Zealand Needle Exchange Programme

- Pharmac Te Pātaka Whaioranga website: Maviret for treating hepatitis C

- Stick it to Hep C – information in English and Māori

-

* This article was reviewed by Professor Ed Gane, chair of the Hepatitis C Implementation Advisory Group and deputy director of the New Zealand liver transplant unit, based at Te Toka Tumai Auckland.

* Thanks also to: The national and regional hepatitis C programme leads for their time and contributions to the development of this resource.References

- World Health Organization. (2023). Hepatitis C (fact sheet).

- Pinchoff, J., Drobnik, A., Bornschlegel, K., Braunstein, S., Chan, C., Varma, J. K., & Fuld, J. (2014). Deaths among people with hepatitis C in New York City, 2000-2011. Clinical Infectious Diseases, 58(8), 1047-54.

- World Health Organization. (2016.) Global Health Sector Strategy on Viral Hepatitis 2016–2021.

- Ministry of Health. (2021.) National Hepatitis C Action Plan for Aotearoa New Zealand – Māhere Mahi mō te Ate Kakā C 2020–2030.

- GBD 2019 Europe Hepatitis B & C Collaborators. (2023.) Hepatitis B and C in Europe: an update from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet Public Health, 8(9), e701–16

- Te Whatu Ora — Health New Zealand. (2023.) Hepatitis C.

- Gamkrelidze, I., Pawlotsky, J. M., Lazarus, J. V., Feld, J. J., Zeuzem, S., Bao, Y., Gabriela Pires Dos Santos, A., Sanchez Gonzalez, Y., & Razavi, H. (2021). Progress towards hepatitis C virus elimination in high-income countries: An updated analysis. Liver International, 41(3), 456-63.

- Research Review. (2023). Update on hepatitis C elimination in New Zealand.

- Pharmac. (2023). Te Whatu Ora Maviret dispensings web tool (restricted access).

- Community Health Pathways. Chronic hepatitis C.

- Pharmac. (2018). Decision to fund a new hepatitis C treatment (Maviret) and to widen access to adalimumab (Humira) for psoriasis.

- New Zealand Formulary. Glecaprevir + pibrentasvir.

- Medsafe. (2023). New Zealand data sheet: Maviret.

- AbbVie. (2023). Maviret – glecaprevir/pibrentasvir.

- Pharmac. (2022). Maviret for treating hepatitis C.

- BPAC. (2019). Hepatitis C management in primary care has changed.

- Expert Panel on Gastrointestinal Imaging: Horowitz, J. M., Kamel, I. R., Arif-Tiwari, H., Asrani, S. K., Hindman, N. M., Kaur, H., McNamara, M. M., Noto, R. B., Qayyum, A., & Tasneem, L. (2017). ACR appropriateness criteria: chronic liver disease. Journal of the American College of Radiology, 14(11S), S391-405.

- Fraser, A. (2022, Sept 28). Eliminating hepatitis C: Still some way to go, so what needs to change? New Zealand Doctor.

- Te Whatu Ora — Health New Zealand. (2023). Regionally led integrated approach to the delivery of hepatitis C services.

- Medsafe. (2022). New Zealand Data Sheet: Harvoni (ledipasvir 90mg, sofosbuvir 400mg) tablets.

- Te Whatu Ora. (2019). Guidance to support the implementation of regional services to deliver identification and treatment for people at risk of or with hepatitis C. Version 4.

- Medsafe. (2022). Minutes for the 69th meeting of the Medicines Classification Committee, 25 October 2022. 6.1b Glecaprevir and pibrentasvir — proposed change to prescription classification statement (Health New Zealand, Long Term Conditions).

- New Zealand Gazette. (2023, Sept 6). Classification of Medicines.

- Te Whatu Ora. (2023). Improving access to hepatitis C treatment in the community.