Series focuses on medicines equity

This year, Kai Tiaki Nursing New Zealand will be publishing a series of articles supplied by He Ako Hiringa to support nurses’ professional development.

He Ako Hiringa is a clinical education programme for primary care clinicians delivered by Matui Ltd, a joint venture between The Health Media – publisher of New Zealand Doctor|Rata Aotearoa and Pharmacy Today|Kaitiaki Rongoā o te Wā – and health data company Airmed.

The programme is funded by PHARMAC Te Pātaka Whaioranga and aims to raise awareness of health inequities and improve access to funded medicines for those who are missing out. Priority populations include Māori, Pacific peoples, rural communities, former refugees, and those living in high socioeconomic deprivation.

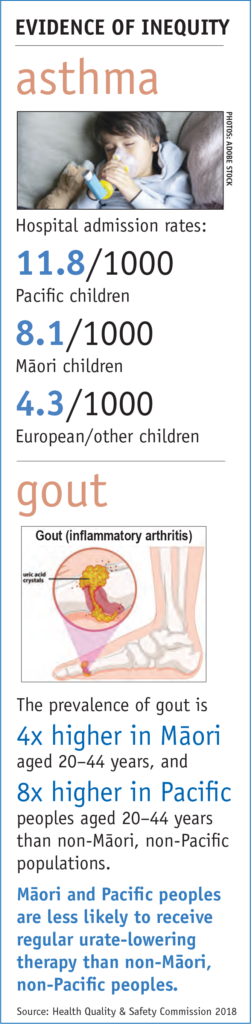

To have the biggest impact on patient health, He Ako Hiringa will also focus on four conditions significantly amenable to treatment with medicine. These are asthma, cardiovascular disease, diabetes and gout. Five main drivers of medicine access equity have been identified: medicine availability, accessibility, affordability, acceptability and appropriateness. Nurses can have a huge impact on these drivers.

PHARMAC’s former acting medical director, Ken Clark, says health professionals have a big role to play in access to medicines in New Zealand. He hopes providing free resources and tools will promote the responsible use of pharmaceuticals and encourage more equitable access.

The release of the Waitangi Tribunal report on primary health care, the investigation of the Health and Disability System Review Panel and a growing swathe of published research underlining inequitable health outcomes for Māori and Pacific peoples and disadvantaged populations, add to the zeitgeist.

PHARMAC Te Pātaka Whaioranga, the government health agency that decides which medicines and medical devices are funded, has added its voice, with a determination to eliminate inequity in access to medicines. A new programme – He Ako Hiringa – aims to drive that target.

An end to inequity in medicine access: it’s a bold call from PHARMAC and one that requires a commitment beyond your standard government agency undertaking. The agency is focused on five key drivers – medicine availability, accessibility, affordability, acceptability and appropriateness – with the aim of changing people’s lives. And those who prescribe, dispense and deliver medicines are being called to drive this change.

In Achieving medicine access equity in Aotearoa New Zealand: Towards a theory of change, published last year, PHARMAC lays down the gauntlet – everyone involved in health care needs to facilitate equitable access to funded medicines. It gives Māori, as Te Tiriti o Waitangi partners, highest priority in this plan for change.

“Medicine access equity means that everyone should have a fair opportunity to access funded medicines to attain their full health potential, and that no one should be disadvantaged from achieving this potential.” That’s the definition PHARMAC is working from.

According to the Ministry of Health in its Health and Independence Report 2016, when compared to other New Zealanders, “Māori and Pacific people are two to three times more likely to die of conditions that could have been avoided if effective and timely health care had been available”.

As PHARMAC puts it: “Treating people equally under the current system will never eliminate inequities.”

At the helm of PHARMAC’s commitment to equity is its manager of Access Equity, pharmacist Sandhaya (Sandy) Bhawan.

Bhawan was raised in Fiji, and was inspired to study pharmacy by an uncle who ran a pharmacy there. As a child, Bhawan recalls seeing locals knocking on her uncle’s door after hours for help.

The social upheaval wrought by Fiji’s 1987 coup saw her family emigrate to New Zealand. After attaining a science degree from Victoria University, Bhawan worked as a science technician before becoming the first Pacific student to finish top of the class when she graduated with a pharmacy degree with honours from the University of Otago in 1996.

It was in 2012, while working at Te Awakairangi Health Network, a primary health organisation (PHO) serving high-needs populations in the Hutt Valley, that her passion for improving access to medicine took shape.

She recalls a particular moment when she was referred a patient with diabetes who had missed several appointments. The patient was not picking up repeat prescriptions nor undertaking requested lab tests.

“When she came, I was prepared with my spiel, my agenda, a list of reasons she ought to be taking her medication, including benefits for her whānau and her quality of life.

“She stopped me and said, ‘It’s not that I don’t want to take these medications: I just don’t have the money to renew the prescriptions every three months. Isn’t taking some every second or third day better than not taking it at all?’ ”

‘The majority of the time, people absolutely know the reasons why medicines are prescribed and ought to be taken – it’s just their social circumstances are so dire…’

—Sandy Bhawan

Bhawan says she thinks of that patient every day.

“The majority of the time, people absolutely know the reasons why medicines are prescribed and ought to be taken – it’s just their social circumstances are so dire… health seems to be the last priority amidst other things they are facing.”

Systems lie at the heart of medicines access equity, she says.

And knowing that, clinicians might be inclined to throw their hands in the air, thinking the structural challenges hamper any potential to have an impact on inequity.

But, Bhawan says, clinicians can make a big difference by partnering with NGOs and following campaigns to reduce the prevalence of targeted diseases and by using audit tools to monitor patient outcomes.

To this end, PHARMAC has contracted clinical education and data analytics company Matui to increase awareness and action on medicine access equity by providing resources to support primary health care professionals. Matui is a joint venture between health data science company Airmed and health care communications company The Health Media.

The programme, He Ako Hiringa, follows in the footsteps of work carried out by providers of CPD for health-care professionals, BPACnz, based at the University of Otago, and the Goodfellow Unit, based at the University of Auckland.

‘Four conditions: gout, cardiovascular disease, diabetes and asthma, they are our biggest priorities.’

Anna Mickell, programme manager for He Ako Hiringa, highlights its goals.

“The aims of He Ako Hiringa are easy to understand. We are calling on primary care clinicians to work together and with us to deal to medicine access equity once and for all.”

‘Clinicians can’t fix housing, clinicians can’t fix the economy… What clinicians can do is give patients access to medicine and help them persist with taking it.’

—Anna Mickell

With a focus on conditions amenable to treatment with medicines, and patient groups who tend to experience higher levels of inequity, He Ako Hiringa aims to have the biggest impact on patient health possible.

“Four conditions, gout, cardiovascular disease, diabetes and asthma, are our biggest priorities. We know the root causes of disparities in treatment of these conditions are social and one key way we can assist in reducing these social inequities is by getting people access to medicine.”

Mickell explains that while the problem is complicated, clinicians can make a difference.

“Clinicians can’t fix housing, clinicians can’t fix the economy, but they can still do something meaningful. What clinicians can do is give patients access to medicine and help them persist with taking it. So let’s work on that and get this right for the patients who have been left behind.”

Change starts with clinicians looking at their behaviour. That is the experience of clinicians interviewed for this article – GPs, pharmacists and nurse practitioners uncovering inequity and seeking ways to improve outcomes for patients.

In Whangārei’s Otangarei, a suburb where 48 per cent of homes are state houses, concern for the health of whānau was the catalyst for the small thriving community getting behind the establishment of the local health clinic.

Te Hau Āwhiowhio ō Otangarei Trust nurse practitioner Margaret Hand (Te Roroa, Ngāti Whātua) works in the nurse-led clinic with an enrolled population of 1800 predominantly Māori patients.

‘Patients will often tell you what they think you want to hear rather than what actually matters for them. They’re trying to make you feel good. That’s why having an honest conversation is important.’

—Margaret Hand

A common theme for many patients is wanting to live long enough to see their mokopuna (grandchildren) grow up, but sadly this is not always the case.

Lack of a living wage is one of the most inequitable factors affecting patients, Hand says.

“Try living on $40 a week. Many patients will never admit to this, but this is the reality of those living on the lowest income in New Zealand.”

For Hand, access to medication means asking patients a really hard question, namely, “Can you afford to pay for your medications?”

“I guess most of us think if we ask that question it will create more work and of course they will say ‘no’. The answer is often ‘yes, but only on pay day’. That’s two days away, and I need them to start their diuretic today.

“Patients will often tell you what they think you want to hear, rather than what actually matters for them. They’re trying to make you feel good. That’s why having an honest conversation is important,” she says.

A solution is trying to walk in the patient’s shoes and coordinate wrap-around services and good communication with pharmacists, Hand says.

The use of standing orders also helps improve access to medicines. Three clinicians from the trust are involved with the multidisciplinary Northland Medicines Management Group that is developing a peer-reviewed set of standing orders.

Hand says her team is innovative and creative. These are the credentials needed to work at Te Hau Āwhiowhio ō Otangarei to reduce inequity in access – not only to medicine, but in all areas of health and wellbeing.

In the far south of the country, University of Otago Māori health researcher and Invercargill GP Sue Crengle (Kāi Tahu, Kāti Māmoe, Waitaha) knows doctors feel uncomfortable if they think they are not delivering their best.

‘It’s easy for inequities to slip into our practice without us being aware they have.’

—Sue Crengle

Running prescribing audits on their own data can help clarify how well they are doing, Crengle says.

She practises two half days per week at the Invercargill Medical Centre, a practice with a variety of ages, ethnicities and deprivation profiles among its 13,000 patients, about 2000 of them Māori.

She says while much of the primary health care system is excellent, “it’s easy for inequities to slip into our practice without us being aware they have.”

Crengle recommends the health literacy process “teach-back”, to check patients’ understanding of information that has been shared with them. Teach-back supports communication between health professionals and patients/whānau by providing an opportunity for the health professional to check how clearly they have communicated important information, and to “fill in the gaps” if needed.

“Being Māori, I’ve been committed to Māori health from very early on in my career,” Crengle says.

“The foundations of health and wellbeing are unequally distributed, so we are more likely to have histories of deprivation, risky occupations – the whole gamut of social determinants of health. We also experience differences in access to and quality of care.

“If you look along a clinical pathway, for example bowel cancer, you see a similar incidence in populations, but Māori mortality is much worse. But there’s not one big thing we can fix – it’s a little bit of a lot of things right along the pathway.”

‘Having the right conversations is essential, specifically about gout.’

—Kevin Pewhairangi

Gisborne pharmacist Kevin Pewhairangi (Ngāti Porou, Ngāti Ira, Te Aitanga a Hauiti, Ngāti Whakaue) established Horouta Pharmacy in 2019 to challenge inequity by reducing the physical barriers to access and positioning the pharmacy in the high-needs neighbourhood of Inner Kaiti, across the river from the city centre.

“For parents pushing their babies in the pram in the rain having to get to the health centre in the city, that doesn’t tell me equity. We decided it was appropriate to put a pharmacy on this side of the river.”

“For parents pushing their babies in the pram in the rain having to get to the health centre in the city, that doesn’t tell me equity. We decided it was appropriate to put a pharmacy on this side of the river.”

Even though the next pharmacy might not seem too far away, at three to four kilometres, for people without cars or with illegal cars, that’s not ideal, Pewhairangi says. His pharmacy also offers courier delivery up to 2.5 hours away in remote East Cape, where there are no pharmacies.

Further barriers exist within the pharmacy itself. Pewhairangi says the ”four-walls, white-jacket approach” may give patients the perception that they are being talked down to. Pharmacists need to relax the environment and make themselves and their services approachable.

Having the right conversations is essential, he says, specifically about gout. PHARMAC’s reporting shows gout is over-treated with anti-inflammatories and under-treated with allopurinol.1

Pewhairangi recommends all health practitioners undergo a Māori cultural experience to improve their understanding of te ao Māori.

Just two per cent of pharmacists are Māori and that needs to change, he says. Greater Māori representation in the health workforce would bring a better connection with Māori and whānau, greater understanding of medicines and, ultimately, improved health outcomes.

Back up north in Whangārei, Te Whareora o Tikipunga owner and GP Aniva Lawrence says her high-needs clinic does its best to reduce inequity from the moment patients step through the door.

The clinic offers careful, cross-cultural communication in relaxed, unhurried medical appointments, Lawrence says. Even small things can make a difference, for instance “if names are pronounced incorrectly patients are less likely to open up and disclose the things that are worrying them”.

She draws her inspiration to improve health outcomes from her Samoan family, from the tragedy of seeing people die before they should.

“My grandmother had lung cancer caused by smoking. From an equity aspect, those things directly impact on how you view the world. Sometimes the systems are against populations, or set up to deliver in an inequitable way.

“When junior doctors are placed with us, I say you spend six years learning medical language then six years un-learning. It’s important to be able to relate to all walks of life.”

‘When junior doctors are placed with us, I say you spend six years learning medical language then six years un-learning. It’s important to be able to relate to all walks of life.’

—Aniva Lawrence

Learning to create equity – join us

Achieving medicine access equity in Aotearoa will be no mean feat, but clinical education and data analytics company Matui plans to encourage change with its new programme, He Ako Hiringa.

He Ako Hiringa provides free evidence-informed and data-led educational resources for primary care clinicians. The focus is on reducing medicine access inequities and on conditions amenable to treatment with medicine. Learning opportunities are provided through a variety of platforms – tailored to what works best for the clinician.

Clinicians also have access to their prescribing data through the He Ako Hiringa EPiC Dashboard – EPiC stands for Evaluating Prescribing to Inform Care. The dashboard is an interactive tool that shows comparative prescribing rates and trends, includes narratives on what’s going well and provides links to further resources.

He Ako Hiringa‘s name highlights its educational goals. Ako means to learn or study, while Hiringa means energy, perseverance, determination, inspiration and vitality.

Find out more on the He Ako Hiringa website.

Te Whareora o Tikipunga has an enrolled patient population of around 4000, 78 per cent of whom are Māori. Most of the staff are also Māori or Pacific.

The clinic aims for patients to be able to see a regular doctor for continuity of care. Staff have weekly meetings to talk about whānau they are working with. They keep an eye on data showing people who are overdue for diabetes check-ups, provide education on the genetic factors affecting gout, provide outreach to patients who might otherwise drop off the radar, and offer advice and treatment to people with mental health challenges.

Health improvement practitioners, health coaches and social workers are all on the team and virtual consultations are on offer.

The big picture: “When people… feel like they have more control over their wellbeing, they’re empowered to make those changes themselves,” Lawrence says.

An unusual feature of the practice is a shared lunchroom with the pharmacy next door. That pharmacy is Unichem Buchanan’s Kiripaka Pharmacy.

He delivered the medication following the kuia’s discharge from hospital on a Friday afternoon, and spent almost an hour talking with whānau and answering their questions.

Owner and pharmacist Iain Buchanan recounts his recent experience building a relationship with a whānau whose kuia required palliative care. Good service began with stepping out from behind the pharmacy counter.

Buchanan explains that he delivered the medication following the kuia’s discharge from hospital on a Friday afternoon, and spent almost an hour talking with whānau and answering their questions.

“That allowed me to understand what the whānau’s requirements were,” he says.

While the kuia has since passed away, the constructive relationship between whānau and pharmacist remains.

‘We’ve created an atmosphere in which we’re there to help people without telling them what to do. We’re helping them to make good choices.’

—Iain Buchanan

Buchanan says about his community: “We’ve created an atmosphere in which we’re there to help people without telling them what to do. We’re helping them to make good choices. It’s more than simply saying, ‘Here is the medication, here are the side effects.’ ”

His experience tells him that Māori especially appreciate relationships being formed and the clinician understanding where they are coming from.

Earn 1.5 CPD hours

Nurses can claim 1.5 professional development hours by

- reading this article

- reading PHARMAC’s document Achieving medicine access equity in Aotearoa New Zealand: Towards a theory of change, and

- watching He Ako Hiringa’s video Medicine access equity: A call to action.

Both the video and PHARMAC report can be found on the He Ako Hiringa website

He recommends being mindful of the role family hierarchy plays, and offering an environment in which patients don’t feel they’re wasting anyone’s time or feel they should already know everything. He also advises clinicians to offer 0800 numbers for people who struggle to have credit on their cellphones, offer flexible pharmacy opening hours, and make the most of targeted programmes such as Gout Stop.

Buchanan is bold in his view of pharmacy’s role. Boldness is also plain in the pages of PHARMAC’s medicine access equity plan.

In her foreword, PHARMAC chief executive Sarah Fitt writes: “We deliberately chose to be bold, as we know that change is needed.”

The agency aims to become a “tenacious influencer”, nudging other decision and policy-makers in the direction of improving health equity, which is one of the Government’s four priorities for health.

Fitt says: “But we can’t achieve change alone – it requires committed collaboration across the whole health system.”

Interviews by Northland journalist Michael Botur