Celebration ‘a piece of history’

A midwinter gathering of nursing luminaries in Parliament’s Grand Hall this year was a “fabulous” event to mark the historic 1973 shift of nurse training out of hospitals and into the education sector, say attendees.

It included two dames of nursing — Margaret Bazley and Judy Kilpatrick — as well as long-time Māori nursing educator Hemaima Hughes, Māori health professor Denise Wilson and former chief nursing officer Jane O’Malley — one of the first to complete the early nursing diploma.

“It was like a piece of history happening before us,” said nurse leadership consultant Liz Manning, who helped organise the event in June.

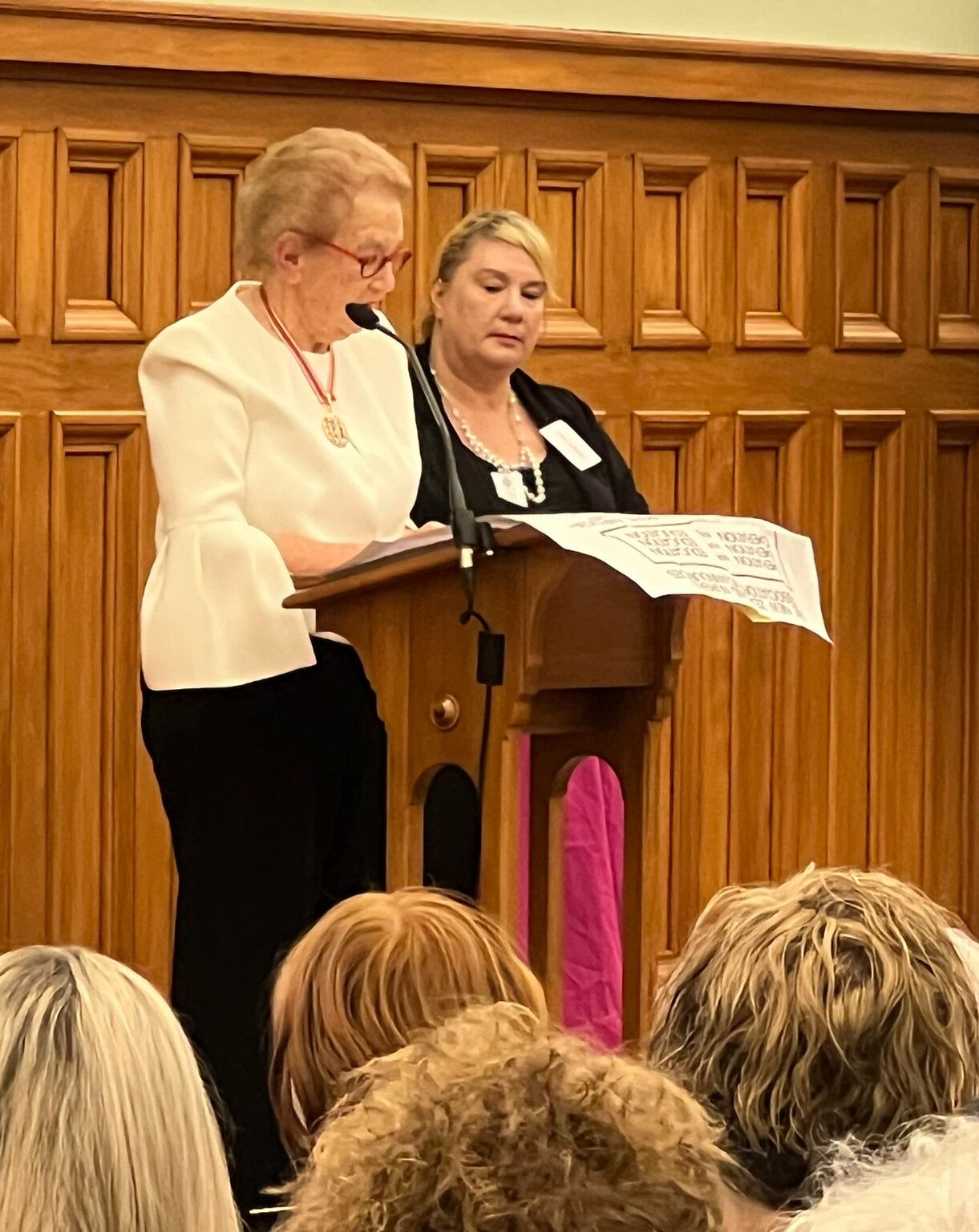

“Dame Margaret Bazley stood up and did 20 minutes [speaking] – it was totally unexpected, as we hadn’t been able to get hold of her. It was astonishing. She did a wonderful speech.”

Victoria University’s nursing and midwifery head Kathy Holloway said despite a few challenges and last minute speaker cancellations, it had turned into a “seamless” night. “Like all good nurses, we just got on with it — made it seamless.”

NETs co-chair Ruth Crawford said it was “really wonderful having people who had that history to speak up”.

Wilson — who spoke of the pressing need to make cultural safety a reality after decades of rhetoric — said it was “really good to come together and reflect on that time – and also to connect with people you’ve lost connections with over the years”.

Hughes, who was involved with designing the bachelor of nursing Māori now in its ninth year at Te Whare Wānanga o Awanuiārangi, told Kaitiaki it was a response to the “cry of our people needing to be cared for by Māori”.

“I think it’s awesome that we’re celebrating 50 years — we should be celebrating, nursing education has come a long way,” long-time educator Johanna Rhodes told Kaitiaki Nursing New Zealand. “But the thing I’m most concerned about is the future of nursing education and, ultimately, the patients.”

Nursing leaders spanning decades — including those who had experienced the shift such as Dame Margaret Bazley — gathered earlier this year at Parliament’s Grand Hall to mark the 50 year anniversary since nurse training moved into the education sector.

The 1971 Government-commissioned Carpenter report recommended moving nurse training out of hospitals in response to high dropout rates and fears of trainee exploitation. In 1973, two pilot programmes began in Wellington and Christchurch. Today, there are 20 schools of nursing around Aotearoa, New Zealand, including universities, Te Pūkenga/polytechnics and wānanga.

‘The pay parity gap between nurses in tertiary sector and industry is very marked now. What happens if you can’t staff, you can’t run, a proper school?’

Rhodes — who has worked in nursing education for 18 years, including five as Southern Institute of Technology (SIT)’s head of nursing — said nursing schools were shedding staff to better paid jobs elsewhere.

$40,000 pay gap

Similarly skilled nurses in the clinical workforce could be paid up to $40,000 more per annum, Rhodes said.

“The pay parity gap between nurses in tertiary sector and industry is very marked now. What happens if you can’t staff, you can’t run a proper school? What are you going to produce at the end and what does that mean for patient safety?”

Tertiary funding pressures were also worrying schools, she said. Massey University is axing its Albany-based nursing degree from next year, while Victoria University’s nursing department survived proposed cuts (although its midwifery stream is under review).

‘It’s about how do we create an environment where Māori feel they belong and do have a rightful place?’

All this had left nursing education in an “extremely vulnerable” position, Rhodes said. “Thinking about the next 50 years of education – what does that look like?”

Nursing Education in the Tertiary Sector (NETS) network co-chair Ruth Crawford agreed the pay gap made it difficult to recruit and keep staff, especially with such high costs of living.

“We’re often offering them a drop in salary — so that’s the difficulty we’ve got. We also have some staff leaving education to return to practice because they can get better salaries.”

NETS was working with Te Pūkenga to increase staff salaries and she hoped this would happen by the end of the year.

“Increase the salary for nursing academics – that’s what they’ve got to do and that’s what we’re looking for. We’re expecting a positive response.”

Te Pūkenga said it was “reviewing” salary rates for its nursing programmes’ staff, as part of moves to attract and retain them, as well as ways of building up student numbers.

Along with the rest of the education sector, Te Pūkenga said it, too, was being impacted by the skills shortage. Of 466 nursing staff positions across its 15 institutes offering nursing programmes nationally there were currently 64 vacancies — a vacancy rate of about 14 per cent.

Māori nurses are ‘taonga’

Auckland University of Technology (AUT) professor of Māori health Denise Wilson (Tainui, Ngāti Porou ki Harataunga, Whakatōhea, Ngāti Oneone, Ngāti Tūwharetoa) said more Māori nurses, including educators and students, were needed for a healthy future.

“It’s about how do we create an environment where Māori feel they belong and do have a rightful place? It’s about recognising that Māori nurses are Māori first, then nurses – not nurses first, then Māori”

Māori nurses were “taonga” (precious) and key to better outcomes for Māori. They must be better supported in both the education and clinical workforces, said Wilson, who spoke at the celebration.

Over the years, she had seen Māori nurses appointed into academic positions at low levels. “The glass ceiling for them for growth and opportunities is low – so how do we recognise that?”

“We acknowledge feedback from nursing kaimahi on the challenges of remuneration compared to external market opportunities, which has had an impact on retention.” a statement said.

‘Crisis’ point

Head of Whitireia’s nursing school Carmel Haggerty has warned nursing education was reaching “crisis point”.

The recent nurses’ pay equity settlement alongside pay rises across the health sector had left nursing educators and the education sector behind, Haggerty wrote in an April report called Nursing academic staff – recruitment and retention issues. Rising living costs had compounded the problem, with many tutors unable to make ends meet, she wrote.

‘Increase the salary for nursing academics – that’s what they’ve got to do.’

Nurse educators had many years’ clinical experience and their salary range needed to be lifted to $90-106,000 to attract and keep them, she said. Currently, the starting salary for tutors (with allowances) was around $79-83,000, the report said.

“At Whitireia over the last 12 months, in Te Kura Hauora, we have had to re-advertise six times to fill vacant positions. Although there are interested applicants, they have often declined the position once the salary offer is made.”

In August, all 20 nursing schools released a joint statement calling for urgent support and pay parity for their “at risk” workforce. It warned fewer educators would mean fewer students at a time of high need for a locally trained workforce.

They also demanded better support for Māori and Pacific nursing academics and clearer academic pathways for all RNs.

Clinical placements ‘challenging’

Rhodes said short-staffing in the clinical workforce also made it hard to find good quality placements and preceptors for students.

While it was fine for students to have a “real” experience of understaffing, “I don’t think they should be experiencing that consistently and not learning”, she said.

“It’s a real spiral of things which to me puts nursing education at risk. Because if students have bad experiences or consistently bad experiences, they’re either going to withdraw, or they’re going to register and probably not stay in nursing for a long period of time — because they themselves will burn out.”