The Te Whare Tapa Whā model of wellbeing is a framework that has been inculcated into nursing students as a foundation for future nurses to address Māori health.

However I believe this model is too simplistic to fully address the complexities of contemporary health care, particularly when responding to the diverse and evolving needs of Māori patients.

Role of a Māori nurse

A crucial part of addressing these evolving needs is increasing the number of Māori nurses in the health workforce. Māori nurses can significantly improve the delivery of culturally safe care and improve Māori health outcomes — due to their Māori identity and values, their use of tikanga (cultural customs) and the deep connection they can make with Māori patients through whanaungatanga.

The health workforce badly needs more Māori nurses to reflect the proportion of Māori in the overall population. And as more Māori nurses enter the profession, they can also help shape health-care practices and policies to be more inclusive and responsive to Māori health needs.

The kōhanga reo generation in nursing

I am a product of the kōhanga reo movement, a generation born from the reclamation of te reo and tikanga Māori. Forty-three years ago, when te reo Māori was on the verge of extinction, kaumātua throughout Aotearoa started the kōhanga reo movement, setting up pre-schools with total immersion in te reo and tikanga Māori.

Growing up in Māori medium education, and through my whānau, I have been fortunate to be immersed in te āo Māori.

This upbringing has shaped my identity and worldview, and has triggered my curiosity as to why nursing institutions and most health-care services are using a framework for Māori health that is almost 40 years old. It was created in a time of Māori language revitalisation and it can be argued that this framework has successfully served its purpose.

I am a product of the kōhanga reo movement, a generation born from the reclamation of te reo and tikanga Māori.

Since 1980, Māori culture has experienced significant growth, revitalisation and reclamation. Health care needs to evolve to reflect this growth and offer models of care that are truly responsive to the needs of Māori communities today and in the future.

This growth will only continue with the next generation of tamariki who have been raised in kōhanga reo, kura kaupapa (Māori immersion schools) and kura ā iwi (tribal schools).

What is Te Whare Tapa Whā?

The Te Whare Tapa Whā model was developed in 1984 by Tā Mason Durie. It uses the structure of a wharenui (meeting house) with four pillars representing the cornerstones of Māori well-being, taha tinana (physical health), taha wairua (spiritual health), taha hinengaro (mental health), and taha whānau (family health), which are all connected to whenua (land), the foundation of the wharenui.1

It maintains that when one pillar of the wharenui is weak, an individual is unbalanced or unwell.1 This model reflects a Māori perspective of wellbeing and remains influential in shaping culturally appropriate care towards, not only Māori, but everybody. However, it is important to note that this model was created for non-Māori to better understand a Māori perspective of wellbeing.

Current practice of Te Whare Tapa Whā

Health-care providers in Aotearoa are encouraged to use Te Whare Tapa Whā across all settings, including hospitals and community health services, to provide holistic and culturally appropriate care.

Whānau ora community nursing services use this model to develop tailored care plans.2 Many hospitals also use it for patient assessments, ensuring all aspects of a patient’s health are addressed.

In mental health services, this model is valued for its holistic approach, addressing the interconnected dimensions of hauora (health). It enables a diagnosis and treatment plan to consider historical, social, cultural, familial and psychological domains of mental illness. This provides a contrast to a model of mental health care focused on managing chemical imbalances in the body.3

Insights into Māori health

Significant health disparities exist between indigenous and non-indigenous populations. Māori, who are indigenous to Aotearoa, are over-represented in statistics for chronic diseases such as cancer, diabetes and cardiovascular disease.

On top of that, life expectancy for wāhine Māori is 77 years and tāne Māori 73 years, compared to Pākeha females, 84 years, and males, 81 years.4 These health inequalities are heavily linked both to colonisation, which led to loss of land and cultural identity, and to systemic racism within the health-care system.5

The Te Whare Tapa Whā model has provided significant benefits in addressing the health-care needs of Māori individuals. Since its establishment, it has significantly influenced Aotearoa, becoming a pre-eminent model of care by the 1990s, and it continues to influence policies, teaching, thinking and nursing.

Evidence shows that Māori whānau feel empowered when health-care professionals adopt it, as it means they are likely to address the diverse needs of Māori patients, fostering trust and collaboration.6 Māori engagement and satisfaction in health care are improved when Māori values are integrated into care,7 while cultural competency is enhanced when health-care professionals use the model to gain a deeper understanding of patient presentations.8

It is recognised in hospice standards for palliative care, to ensure that all dimensions of an individual are attended to, which is crucial for end-of-life care.9

What are its limitations?

While Te Whare Tapa Whā is a highly regarded health framework and has been the foundation for other Māori health frameworks to build on, its limitations have been identified.

Its implementation into mainstream services has faced challenges, due to the health service’s primary focus on physical measurable health outcomes.4 Also, time constraints, nursing shortages and lack of cultural training and competency can limit the ability of health staff to put it into practice.

While Te Whare Tapa Whā is a highly regarded health framework and has been the foundation for other Māori health frameworks to build on, its limitations have been identified.

Meanwhile the Ministry of Health has reported little improvement in Māori health — for example, many significant health-care needs, such as chronic pain, heart failure, diabetes and arthritis, have increased over time.10

The health-care service’s use of Te Whare Tapa Whā has failed to uphold Māori culture and values, as required by Te Tiriti o Waitangi.2 One of the most concerning aspects of this failure has been the increase in Māori suffering high levels of psychological distress from 7 per cent in 2011/12 to 22.5 per cent in 2024/25.21 And a study of Māori whānau experiences in palliative care showed a lack of alignment between holistic values and the health care being provided.6

These systemic failures raise critical questions about the implementation of Te Whare Tapa Whā in health care, and whether it is, in fact, best practice.

The Meihana Model — a best practice approach

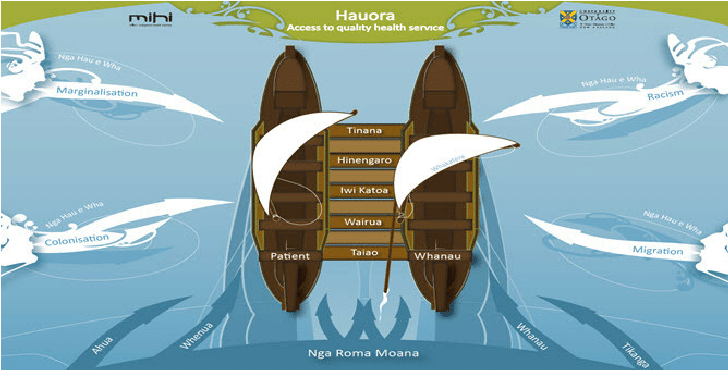

Researchers are now recommending the Meihana Model as best practice. This model, which builds on Te Whare Tapa Whā, was created by Suzanne Pitama, an educational psychologist and leader in Māori health education. She originally developed the model as an assessment tool for mental health, but it can be applied beyond mental health to all health-care settings.11

The metaphor of the model is a waka hourua (a double-hulled canoe) moving across the ocean to reach hauora (access to quality health services). The crossbeams of the waka consist of tinana (physical health), hinengaro (mental health), iwi katoa (wider health and support systems), wairua (spirituality/connectedness) and taiao (person’s environment, including barriers to care).

This model also incorporates nga hau e whā (the four winds which can blow the waka off course) — marginalisation, racism, migration and colonisation. Ngā roma moana (the ocean currents) represent Māori identity, encompassing ahua (a person’s connectedness to their Māori identity), whenua (connection to place and whakapapa), whānau (family relationships and responsibilities) and tikanga (Māori protocols), which help protect Māori wellbeing.

Lastly, whakatera is the sail, which helps navigate the waka, and in health terms, brings together all the elements of the Meihana Model to help inform clinicians in their assessment of the patient and formation of a treatment plan which best fits the person and their whānau.12

This framework can guide practitioners to a deeper understanding of a person’s life and experiences.

This framework can guide practitioners to a deeper understanding of a person’s life and experiences. Considering these factors will help ensure that care is culturally safe, patient-centred and tailored to an individual’s unique needs, which makes it a valuable tool in all health-care environments.

Current practice vs best practice

Te Whare Tapa Whā is the most prominent Māori health model used in health-care services. However, the gaps between the current practice of this model and best practice recommendations of the Meihana Model are significant, highlighting key areas where current practice may be falling short in addressing the health-care needs of Māori patients.

While Te Whare Tapa Whā focuses on the four dimensions of health,13 it fails to mention the social determinants of health, which are fundamental to the Meihana Model. Incorporating ngā hau e whā recognises the influences of colonisation, marginalisation, racism and migration on Māori health outcomes.12

Using the Meihana Model allows practitioners to undertake more complex health assessments, including not only physical and mental health but the social determinants and cultural contexts that influence health.

Both the Te Whare Tapa Whā and Meihana Models share a commitment to holistic health, advocacy for care that aligns with Māori values, and the importance of addressing the multiple dimensions of health with a Māori approach.14

However, the Meihana Model expands the framework beyond the individual and whānau, by acknowledging the broader environmental factors that contribute to Māori health.

Nursing pressures and cultural competency gaps

Current practice differs from the recommended best practice of the Meihana Model for several reasons. Time constraints, resource limitations, and the lack of culturally competent training are significant barriers that health providers face.

Nurses in Aotearoa are struggling with staff shortages, with nurses continually leaving the profession prematurely. During 2023, more than a quarter of nursing shifts were below target staff numbers, with some wards reporting constant understaffing.15 There is evidence that inadequate staffing levels can jeopardise an RN’s ability to form a therapeutic relationship with patients.16

Although Māori culture has been revitalised and expanded, there are still initiatives and policies today that undermine Māori well-being and autonomy.

Te Aka Whai Ora, the Māori Health Agency, was established in 2022, in an effort to grow the Māori nursing workforce and contribute positively to Māori health.17 Unfortunately, the new Government in 2023 disestablished Te Aka Whai Ora and budget cuts left health-care systems across the sector struggling.18

Such changes can lead to decreased satisfaction with care delivery and poorer health outcomes for critically ill patients.19 Although Māori culture has been revitalised and expanded, there are still initiatives and policies today that undermine Māori well-being and autonomy.

Furthermore, nurses may not receive proper training in cultural competency, which is critical for using the Meihana Model with patients. Some Māori RNs have identified a lack of cultural skills, particularly in relation to hauora Māori, in nursing training and in the workplace.20

The Meihana Model requires practitioners to broaden their knowledge and strengthen their cultural skills to provide high-quality care for their patients.11

Building on the foundation of Te Whare Tapa Whā

Te Whare Tapa Whā has provided an effective foundation for understanding Māori wellbeing, ensuring that a Maōri view of health is voiced in health-care systems. Writing this reminded me of a whakataukī — “ko te reo te taikura o te ao mārama” (language is the key to understanding). Te Whare Tapa Whā unlocked the door for both non-Māori and Māori to integrate holistic views of well-being into health care.

However, as new challenges arise, and te reo Māori is revitalised, I believe it is time to build on this foundation with models such as the Meihana framework. This model offers extensive tools for practitioners to address disparities in a modern context, encouraging more health-care practitioners to develop a deeper understanding of Māori that may help to reduce stigma, racism and discrimination in health-care services.

As a result, we may see an increase in Māori accessing health-care services due to the culturally safe care being provided. Nevertheless, Te Whare Tapa Whā will always be a cornerstone of Māori health, deserving our respect and gratitude for the cultural awareness it has brought to the health-care system.

Baxter-Lena Edwards, RN, is a new graduate nurse working in mental health in Northland. She wrote this article while a third-year nursing student at Northtec, and acknowledges the help of senior lecturer Thomas Harding in helping her shape her writing.

References

-

- Durie, M. (1985). A Maori perspective of health. Social Science & Medicine (1982), 20(5), 483-486.

- New Zealand Nurses Organisation [NZNO]. (n.d.). Whānau ora.

- Rochford, T. (2004). Whare Tapa Whā: A Māori model of a unified theory of health. Journal of Primary Prevention, 25(1), 41-57.

- Rolleston, A. K., Cassim, S., Kidd, J., Lawrenson, R., Keenan, R., & Hokowhitu, B. (2020). Seeing the unseen: evidence of kaupapa Māori health interventions. AlterNative: An International Journal of Indigenous Peoples, 16(2), 129-136.

- Paradies, Y., Ben, J., Denson, N., Elias, A., Priest, N., Pieterse, A., Gupta, A., Kelaher, M., & Gee, G. (2015). Racism as a Determinant of Health: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. PloS one, 10(9), e0138511.

- Moeke-Maxwell, T., Collier, A., Wiles, J., Williams, L., Black, S., & Gott, M. (2020). Bereaved Families’ Perspectives of End-of-Life Care. Towards a Bicultural Whare Tapa Whā Older person’s Palliative Care Model. Journal of Cross-cultural Gerontology, 35(2), 177-193.

- Komene, E., Pene, B., Gerard, D., Parr, J., Aspinall, C., & Wilson, D. (2023). Whakawhanaungatanga — building trust and connections: A qualitative study of indigenous Māori patients and whānau (extended family network) hospital experiences. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 80(4), 1545-1558.

- Al-Busaidi, I. S., Huria, T., Pitama, S., & Lacey, C. (2018). Māori Indigenous Health Framework in action: addressing ethnic disparities in healthcare. New Zealand Medical Journal, 131(1470), 89-93.

- Hospice New Zealand. (2019). Standards for palliative care.

- Ministry of Health. (2017). Te Ara Whakapiri: Principles and guidance for the last days of life.

- Pitama, S., Huria, T., & Lacey, C. (2014). Improving Māori health through clinical assessment: Waikare o te waka o Meihana. New Zealand Medical Journal, 127(1393), 55-60.

- Pitama, S., Robertson, P., Cram, F., Gillies, M., Huria, T., & Dallas-Katoa, W. (2007). Meihana Model: A clinical assessment framework. New Zealand Journal of Psychology, 36(3), 118-125.

- Durie, M. (2006). Measuring Māori Wellbeing. New Zealand Treasury guest lecture series.

- Henare, M. (2001). Tapu, mana, mauri, hau, wairua: A Māori philosophy of vitalism and cosmos, in ed J. Grimm, Indigenous Traditions and Ecology: The Interbeing of Cosmology and Community (pp.197-221). Harvard University Press for the Centre for the Study of World Religions.

- New Zealand Nurses Organisation [NZNO]. (2024, May 8). Official nurse unsafe staffing figures genuinely alarming (press release).

- Moloney, W., Boxall, P., Parsons, M., & Sheridan, N. (2017). Which factors influence New Zealand registered nurses to leave their profession? New Zealand Journal of Employment Relations, 43(1), 1-13.

- Lorgelly, P. K., & Exeter, D. J. (2023). Health Reform in Aotearoa New Zealand: Insights on Health Equity Challenges One Year On. Applied Health Economics and Health Policy, 21(5), 683-687.

- NZCTU. (2024). In Better Health? NZCTU analysis of the 2024 health budget.

- Anesi, G. L., & Kerlin, M. P. (2021). The impact of resource limitations on care delivery and outcomes: routine variation, the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic, and persistent shortage. Current Opinion in Critical Care, 27(5), 513-519.

- Huria, T., Cuddy, J., Lacey, C., & Pitama, S. (2014). Working with racism: a qualitative study of the perspectives of Māori (indigenous peoples of Aotearoa New Zealand) registered nurses on a global phenomenon. Journal of Transcultural Nursing, 25(4), 364-372.

- Ministry of Health. (2025). Methodology Report 2024/25: New Zealand Health Survey.