I am writing in response to the Kaitiaki article Community mental health nurses consider stab-proof vests after knife attack. Firstly I would like to send my best wishes to the nurse affected and hope that her recovery goes well.

This may be a contentious topic, considering the severity of this incident, but one comment in the article is an example of the way we speak about drugs that ultimately causes more harm in the health and social sector than most drugs do.

One person quoted in the article acknowledges that the knife attack is a “rare and random incident” but then says: “We’re seeing more of a society that is highly distressed due to social situations and increased drug use — and just generalised antisocial behaviours.”

Social situations and social attitudes play a pivotal role in the experience of illicit drug use. In his 1971 book The drugtakers: The social meaning of drug use, Jock Young describes the connection between the social and the pharmacological effects of a drug.1

He argues that drug-taking is a two-way process where the drug alters the metabolism of the drug-taker, who then interprets the bodily changes into subjective experiences according to expectations, social situation, and prevailing mood. These subjective experiences revert back on to and change an already altered metabolism.1

Therefore, the way society views individual drugs, or drugs as a whole, plays a vital role in the effects of a drug on an individual.

Important to be accurate and specific

This makes it imperative to be accurate and specific when discussing illicit drugs and to stipulate which drugs we are talking about — otherwise the public, and often health professionals who lack experience in this field, are getting inaccurate information.

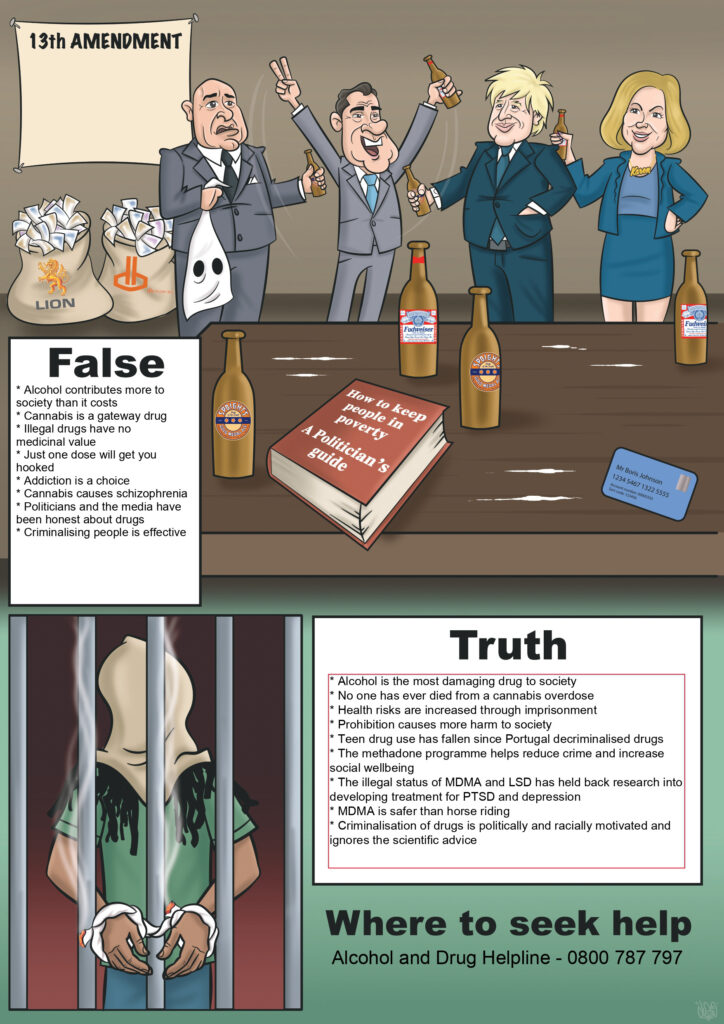

The article did not mention any particular drug, and in doing so, appears to paint all substances as negative, where it is simply not that black and white — many drugs that are currently illegal can have a range of positive effects on users, particularly related to their mental health.

From my experiences working in the mental health and addictions and medical sector, methamphetamine and alcohol are the substances causing the most harm, resulting in admissions to the health system.

From my experiences working in the mental health and addictions and medical sector, methamphetamine and alcohol are the substances causing the most harm.

The harms that are caused by these two substances far outweigh the so-called dangers of other classifications of illegal drugs. Yet methamphetamine gets thrown in with other drugs which are enjoyable and far less harmful; and alcohol is legal and enjoyed by many politicians, including cabinet minister Chris Bishop who, as recently as 2023, owned shares in a craft brewery.2

Cannabis — the world’s oldest medicine — is historically the most stigmatised drug — its users have been criminalised, imprisoned and suffered huge health and social consequences as a result.3

This is despite evidence that shows the “harms” of cannabis use are less than legal drugs such as alcohol, and that state-controlled legalisation would lead to improved health and social outcomes.4, 5

David Nutt, an English professor of neuropsychopharmacology, and an outspoken champion of evidence-based drugs policies, has said the United Kingdom’s National Health Service could save itself billions of pounds a year by fully implementing the legal use of medicinal cannabis.6

It could replace other over-prescribed medications for use, among other things, as a relaxant,7 and to treat seizures,8, 9 eating disorders10 and depression.11

Leading scientists are questioning why people suffering from chronic pain, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and anxiety still face restricted access to these legally available treatments, with costly private prescriptions often their only option.12 The same could be said for New Zealand, which, in the current climate, would be a better option for saving the health system money, instead of cutting staff.

One of the conventional narratives is that cannabis “makes you paranoid”. In reality, it is the ongoing criminalisation of, and societal hysteria about, a relatively safe drug that causes the paranoia — the labelling of the drugtaker as “antisocial”, “criminally minded”, or “on the wrong path” etc.

Another label thrown at cannabis is that is a “gateway” to harder drugs. As Carl Hart, a leading psychologist and neuroscientist known for his research on drug abuse and addiction highlights, the vast majority of cannabis smokers do not go on to use harder drugs.13, 14

In the early 1970s, United States President Richard Nixon, who started the country’s war on drugs, appointed a conservative Republican majority to a National Commission on Marihuana and Drug Abuse.15 After 18 months of testimony from dozens of experts, commission chairman Raymond Shafer concluded that cannabis was neither physically addictive nor a “gateway” drug, yet it was heavily criminalised anyway.

Negative narrative

Despite the evidence about cannabis, this negative narrative is still used to this day, including in the debate leading up to New Zealand’s 2020 cannabis referendum. New Zealanders were asked to vote on whether to legalise the sale, use, possession and production of recreational cannabis.

By a small majority, New Zealanders, including a number of health workers, voted against reducing harms to health and social care. The “no” vote was supported by the National Party, including those with links to the alcohol industry — society’s most harmful drug.16, 17 This is a conflict of interest that causes more harm to the health system.

Research on psychedelics

In my research for a master’s in health science, I am investigating the effect on individuals of the criminalising of psychedelic drugs due to prohibitive drug policies. There is limited information available in New Zealand on this specific topic, which is harmful in itself.

However, research does exist on how criminalisation of drug users affects the individual. The negative effects include separation from whānau, financial stress, and stigmatisation by staff in the health system. I have personally witnessed the judgmental attitude of some health staff towards drug users and some of the care given them has been poor.

In terms of psychedelics, and indeed cannabis, you need to question why they are illegal. MDMA (ecstasy), LSD, ketamine, and psilocybin (magic mushrooms) are far safer than alcohol. MDMA has been shown to be less harmful than horse riding.18 Yet we do not stigmatise and criminalise those who enter the health system as a result of falling from a horse.

The negative effects [of criminalisation] include separation from whānau, financial stress, and stigmatisation by staff in the health system.

Scientist Albert Hoffman, who synthesised LSD, took the world’s first known deliberate “acid” trip in 1943. He died in 2008 aged 102, famously taking LSD well into his 90s. Meanwhile, classic psychedelics, ie LSD and magic mushrooms, have been shown to reduce the propensity to commit crime.19, 20 The illegal status of MDMA and LSD has held back research into the development of treatment for PTSD and depression.

Ketamine, which is used legally for anaesthesia but gaining more of a reputation for its psychedelic properties, is a very safe drug.21 Many years ago, I took it recreationally, but it helped me medicinally at a very tough personal time, alleviating depression and helping me see a pathway forward in my life. Why is this considered a crime?

Young people self-stigmatising

Worryingly, we see evidence among youths who vape that they are self-stigmatising about their use, as well as feeling attacked and judged by hypocritical adults.22

Framing addiction as something bad has the effect of further stigmatising an already stigmatised population. For example, it is unhelpful for politicians to label youth vaping as “bad”, as former health minister Ayesha Verral and Finance Minister Nicola Willis did in a radio discussion, especially when evidence shows that such comments worsen the mental health of youth and drug users.

Like many other drugs taken recreationally, vaping is a social connector, while also playing a positive role in the treatment of mental health and addictions patients on the unit where I regularly work.

I speak to many patients about the benefits they get from vaping. They all say it calms them, de-stresses them, and reduces anxiety and boredom. In a society with high levels of social distress, should we not see this as an effective tool that alleviates many issues that arise from stress and anxiety? Or would we rather continue with stigmatisation?

Self-stigmatisation is detrimental to mental health and causes far more harm than vaping does. It can lead to negative self-thoughts, suicide ideation, lack of self care, and social withdrawal.

The mental health and addictions sector is understaffed and is unable to recruit the numbers needed. This should not come as a surprise, considering the negative light shone on mental health and drug use by politicians and the media.

Ongoing misinformation about drugs and the resulting stigmatisation of users needs to be addressed from the perspective of health, not political expediency.

Phil Tansey, RN, PGCert Addiction, PGDip HealthSci, has more than a decade of experience in medical and mental health and addiction nursing. He is currently studying for a master’s in health science, on the topic of criminalising psychedelics.

References

- Young, J. (1971). The drugtakers: The social meaning of drug use. MacGibbon and Kee.

- Parliamentary Service. (2023). Register of pecuniary and other specified interests of members of Parliament 2023. New Zealand Parliament.

- Transform Drug Policy Foundation. (n.d.). Count the costs: The war on drugs and stigma. Transform Drug Policy Foundation.

- Rogeberg, O., Bergsvik, D., Phillips, L. D., van Amsterdam, J., Eastwood, N., Henderson, G., Lynskey, M., Measham, F., Ponton, R., Rolles, S., Schlag, A. K., Taylor, P., & Nutt, D. (2018). A new approach to formulating and appraising drug policy: A multi-criterion decision analysis applied to alcohol and cannabis regulation. International Journal of Drug Policy, 56, 144–152.

- Nutt, D. N. (2021). Cannabis (seeing through the smoke). The new science of cannabis + your health. Yellow Kite.

- Marrinan, S., Schlag, A. K., Lynskey, M., Seaman, C., Barnes, M. P., Morgan-Giles, M., & Nutt, D. (2024). An early economic analysis of medical cannabis for the treatment of chronic pain. Expert Review of Pharmacoeconomics & Outcomes Research, 25(1), 39-52.

- Ghelani, A. (2020). Motives for recreational cannabis use among mental health professionals. Journal of Substance Use, 26(3), 256-260.

- Perucca, E. (2017). Cannabinoids in the treatment of epilepsy: Hard evidence at last? Journal of Epilepsy Research, 7(2), 61-76.

- Hutton, F., Noller, G., & McSherry, A. (2023). A call for cannabis research reform in New Zealand: Why real-world evidence and patients’ voices matter. Drug Science.

- Avraham, Y., Latzer, Y., Hasid, D., & Berry, E. M. (2017). The impact of Δ9-THC on the psychological symptoms of anorexia nervosa: A pilot study. Israel Journal of Psychiatry, 54(3), 44-51.

- Lynskey, M. T., Thurgur, H., Athanasiou-Fragkouli, A., Schlag, A. K., & Nutt, D. J. (2024). Suicidal ideation in medicinal cannabis patients: A 12-month prospective study. Archives of Suicide Research, 1-15.

- Drug Science. (2023, May 3). Are they simply scared of cannabis? Drug Science.

- Hart, C. (2024). Dr. Carl Hart vs Dr. Drew debate: Is marijuana a gateway drug? Dr. Carl Hart, PhD.

- Hart, C. (n.d.). Why do American scientists ignore the benefits of drugs? Dr. Carl Hart, PhD.

- Posner, G. (2020). Pharma: Greed, lies, and the poisoning of America. Avid Reader Press.

- Nutt, D. J., King, L. A., & Phillips, L. D. (2010). Drug harms in the UK: a multicriterion decision analysis. The Lancet, 376(9752), 1558-1565.

- Crossin, R., Cleland, L., Wilkins, C., Rychert, M., Adamson, S., Potiki, T., Pomerleau, A. C., MacDonald, B., Faletanoai, D., Hutton, F., Noller, G., Lambie, I., Sheridan, J. L., George, J., Mercier, K., Maynard, K., Leonard, L., Walsh, P., Ponton, R., … Boden, J. (2023). The New Zealand drug harms ranking study. Journal of Psychopharmacology, 37(9).

- Nutt, D. (2020). Drugs without the hot air: Making sense of legal and illegal drugs (2nd ed.). UIT Cambridge Ltd.

- Hendricks, P. S., Clark, C. B., Johnson, M. W., Fontaine, K. R., & Cropsey, K. L. (2014). Hallucinogen use predicts reduced recidivism among substance-involved offenders under community corrections supervision. Journal of Psychopharmacology, 28(1), 62-66.

- Jones, G. M., & Nock, M. K. (2022). Psilocybin use is associated with lowered odds of crime arrests in US adults: A replication and extension. Journal of Psychopharmacology, 36(1), 46-53.

- Edwards, J. (2023). The revolutionary ketamine: The safe drug that effectively treats depression and prevents suicide. Skyhorse Publishing.

- Graham-DeMello, A., Sanders, C., Hosking, R., Teddy, L., Ball, J., Gallopel-Morvan, K., van der Eijk, Y., Hammond, D., & Hoek, J. (2025). Lived experiences of stigma and altered self-perceptions among young people who are addicted to ENDS: A qualitative study from Aotearoa New Zealand. Tobacco Control.