This article is one of two companion pieces on cultural safety in perioperative care. The other is: A safe environment for Māori patients starts with a safe environment for Māori nurses.

Introduction

Equity is the absence of avoidable or remediable differences among groups of people.1 Health-care providers, institutions, professional organisations, patient representatives and all stakeholders must collaborate to ensure equity in all aspects of care for all patients.2

Key questions

- Do you have an understanding of cultural beliefs and practices important to Māori?

- Are you actively incorporating these into our day-to-day nursing practice?

- How does your perioperative department display equity?

- How are you teaching cultural safety in your department?

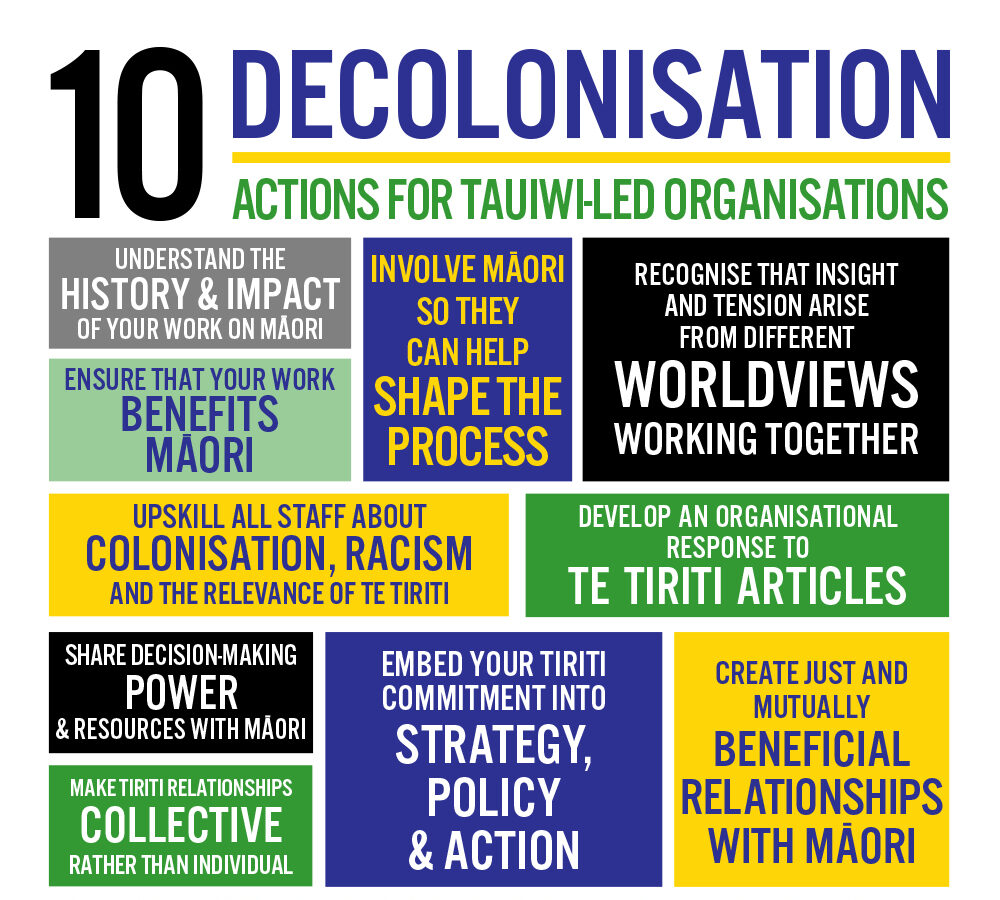

Addressing and eliminating health inequities requires that health professionals and health organisations address the determinants of health inequities, including institutionalised racism, to ensure a health-care system that delivers appropriate and equitable care.3

Health-care professionals must examine themselves and consider the potential impact of their own culture on health-care delivery, including their own biases, attitudes, assumptions and stereotypes to enable provision of culturally safe care.3 To provide culturally safe nursing care in Aotearoa, nurses must also have a sound knowledge of cultural beliefs and practices important to Māori, incorporating them into day-to-day nursing practice.4

Cultural safety

Cultural safety is defined by the Nursing Council of New Zealand as “the effective nursing practice of a person or family from another culture, and is determined by that person or family”.5 Cultural safety in health care relates to the experience of the recipient of nursing services, extending beyond cultural awareness and cultural sensitivity.5

Unsafe cultural practice is defined as any action which diminishes, demeans or disempowers the cultural identity and well-being of an individual.5

The Nursing Council expects all nurses to reflect on their own cultural identity and recognise the impact that their personal culture has on their professional practice. Nurses must incorporate the articles of te Tiriti O Waitangi in their practice.6 This is acknowledged within the professional development and recognition programme (PDRP) domain of professional responsibility.7

Cultural safety requires health-care professionals to influence health care to reduce bias and achieve equity within the workforce and working environment.3

Te Tiriti o Waitangi

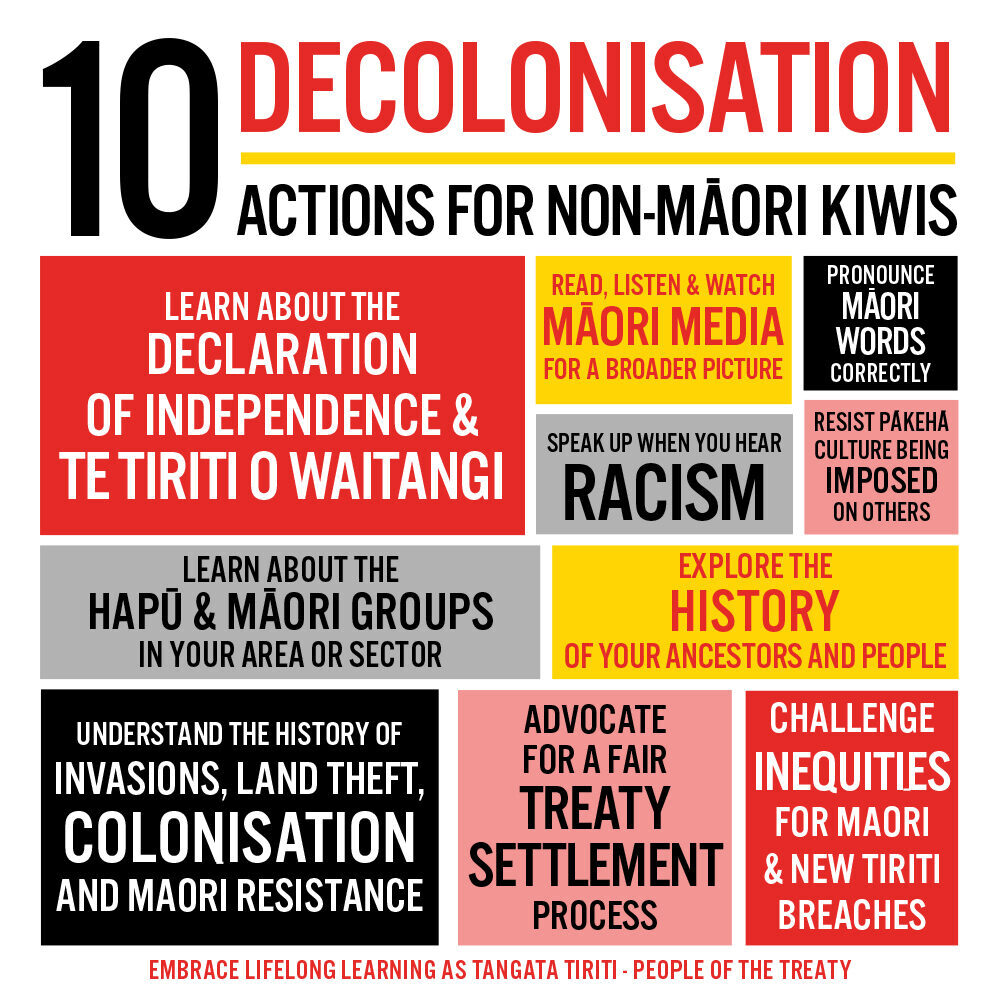

Aotearoa’s original founding document was He Whakaputanga o te Rangatiratanga o Nu Tirene: the Declaration of Independence of the United Tribes of New Zealand, signed in 1831 by 13 Ngāpuhi chiefs.8

In 1840, more than 500 Māori chiefs and representatives of the British Crown agreed to te Tiriti o Waitangi. Most of the Māori chiefs signed a copy in the Māori language, agreeing to give the British queen (Queen Victoria) te kawanatanga katoa (governance or government over the land) while retaining te tino rangatiratanga (the exercise of chieftainship over their lands, villages and taonga katoa – all treasured things). In return, the Crown gave an assurance that Māori would have the queen’s protection and all rights accorded British subjects.9

As health-care professionals in Aotearoa, we must recognise and respect Te Tiriti o Waitangi (Treaty of Waitangi). Te Tiriti provides the health sector with a framework for Māori development, health and wellbeing.10

The Nursing Council defines four principles of Te Tiriti that form the basis of interactions between nurses and Māori health consumers.

- The first principle enables Māori self-determination over health, recognises the right of Māori to manage Māori interests, and affirms the right to development.

- The second principle involves nurses working together with Māori with the mutual aim of improving Māori health outcomes.

- The third principle indicates that nurses must recognise that health is taonga and act to protect it.

- The fourth principle requires that the nursing workforce recognise the citizen rights of Māori and the rights to equitable access and participation in health services and delivery at all levels.5

The historical “three P’s” — partnership, participation and protection, which came out of the Royal Commission on Social Policy in 1986 — are now outdated and said to reflect a reductionist view of Te Tiriti.11 The Nursing Council has recently described five enhanced principles, premised on the Waitangi Tribunal Claim — Wai 2575: the Health Services and Outcomes Inquiry. These are tino rangatiratanga (self-determination), pātuitanga (partnership), mana taurite (equity), whakamarumarutia (active protection), and kōwhiringa (options).10

Tikanga

Tikanga can be described as patterns of appropriate behaviour including customs and rites.12 The concept is derived from the Māori word “tika” which means “right” or “correct”. In Māori terms, to act in accordance with tikanga is to behave in a way that is culturally proper or appropriate.

The basic principles underpinning tikanga are common throughout Aotearoa; however, different iwi (tribes), hapū (sub tribes) and marae (Māori community meeting places) may have their own variations.13

Tikanga encompasses, amongt other things, karakia tapū (incantation or prayers), rāhui (a temporary ritual prohibition), rangatiratanga (self-determination), kotahitanga (unity/oneness), wairuatanga (spirituality), and manaakitanga (showing respect/kindness).12 Values include the importance of te reo (language), whenua (land) and in particular whānau (extended family).14

Tikanga best practice is focussed on Māori as it reflects Māori values and concepts. However, policies and delivery of care are relevant regardless of the patient’s ethnicity as they should reflect best practice, standards of care and processes, helping provide quality of care for everyone.14 Tikanga best practice reflects the intent of tapu (restricted) and noa (free from restriction). For example, food is considered noa and kept separate from bodily functions, which are tapu, therefore anything that comes into contact with the body or its substances must be kept separate from food.14

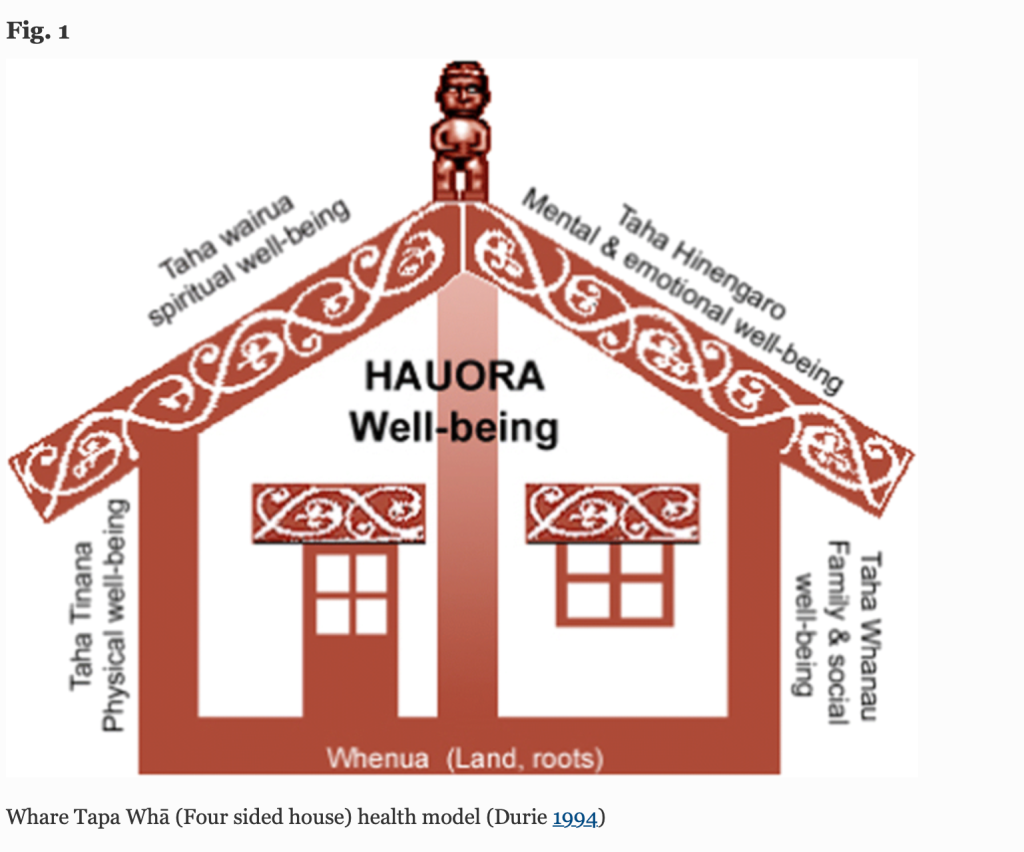

Māori health is a complex interaction with multiple dimensions, extending beyond the physical being and medical diagnoses. Māori identity, beliefs, values and practices are considered significant factors that contribute to holistic wellbeing.5 Te Whare Tapa Whā (the four cornerstones/sides of health) model of health developed by Tā Mason Durie represents a Māori view of health and wellness in four dimensions. These are identified as taha wairua (spiritual health), taha hinengaro (mental health), taha tinana (physical health) and taha whānau (family health).15

Holistic, culturally safe care of Māori patients considers all four of these dimensions. For example, karakia (blessings/prayer) is essential in protecting and maintaining wairua, hinengaro and tinana aspects of a tāngata whaiora (Māori consumers/clients/patients).

Examples of tikanga in practice

All staff must introduce themselves and explain their role and service to the tāngata whaiora (Māori consumers/clients/patients) and whānau during all encounters. Where appropriate, an interpreter should be offered.14

Tāngata whaiora and whānau should be actively encouraged, included and supported by staff to be involved in all aspects of care and decision-making. At all times, tāngata whaiora and whānau should be offered the opportunity for karakia, unless physical care of tāngata whaiora is compromised. If karakia cannot occur, staff must sensitively explain the reasons and discuss options.

Taonga (valuables/heirlooms) worn on the body such as pounamu should only be removed if leaving them on will place tāngata whaiora at risk. Consent is required from tāngata whaiora or whānau before removing taonga and they must be given the option of removing taonga themselves. Wherever possible, taonga should be taped to the tāngata whaiora. Whānau should have the option of caring for removed taonga, or they should be stored in an identified valuables safe.14

One example of tikanga particularly important in the perioperative environment is the removal of body parts, which are considered tapu, regardless of how minor the part/tissue or substance is perceived to be by staff. The patient and whānau must be consulted before removal and return of body parts, tissues and fluids.

In cases where body parts are to be returned to the patient and whānau, these should be returned in a manner that reflects the appropriate tikanga practices that are set in place. They should also be checked by appropriate Māori staff before being returned to the patient’s whānau.16

Staff should give clear verbal explanations of procedures with tāngata whaiora and whānau as early as possible. This is important when the removal or retention of a body part is involved, especially amputations. The procedure needs to be explained, and both verbal and written consent required.

Time should be allowed for consultation between the tāngata whaiora and their whānau, unless their physical wellbeing is at risk. This allows tāngata whaiora to uphold the tikanga of whanaungatanga (sense of family connection) so that they can feel comfortable and more confident with their decision.16

Consent for the retention of all body parts and tissues is required and these must be stored and labelled correctly in case their return is requested. An example of this is during childbirth many Māori request that the placenta is returned to the whānau. This is because the placenta is translated into whenua (placenta/land). Many choose to bury the placenta and plant a tree over it, sustaining new life and making a connection back to the whenua.

This is an important tikanga as it enforces tāngata whenua (association with the land, home), just like the umbilical connection between an unborn child and its mother as well as the belief that Māori come from Papatūānuku (Earth Mother), as though they were born from the land itself.16

Culturally safe care of tūpāpaku (deceased) patients is also highly important in the perioperative environment. Care should be taken to ensure the safety and non-violation of mana (integrity/prestige) and tapu (sacredness of the tūpāpaku at all times. Staff must ensure care of tūpāpaku is performed with compassion, reducing distress to the whānau as much as possible. Any death can be extremely difficult for the whānau to cope with and it is important that an appropriate Māori health service is made available to provide support.17

The whānau will require time with the tūpāpaku as part of the grieving process and should be given as much time as they require whenever possible. Another area should be found for the tūpāpaku and whānau if the operating room is required. The whānau may wish to stay with the tūpāpaku and wherever possible they should be supported to do so. If this is not possible, for example if the coroner specifies, a full explanation should be given.

The whānau should be asked if they want to participate or assist with cleaning and laying out the body and any cultural practices or requests adhered to. Care must be taken with taonga, which may be released to whānau.17

Services should have a predetermined pathway for movement of tūpāpaku. Wherever possible, pathways should avoid public areas and pathways and where food or dirty linen is present wherever possible. Whānau should be allowed to accompany the tūpāpaku when it is being moved. Tūpāpaku should be moved feet first — however the wishes of the whānau should always be respected as to how tūpāpaku are moved.17

Māori nurses

Evidence suggests that a culturally diverse workforce can improve cultural competence of both health systems and health professionals, in turn creating improvements in patient outcomes.2 Māori nurses comprise eight per cent of the Aotearoa nursing workforce.18 The Māori nursing workforce is crucial to the delivery of high-quality, culturally responsive health-care services and for Māori and their family/whānau to feel culturally safe.19

Nurses who identify with Māori ethnicity are critical to enabling achievement of Māori health equity.19 The Aotearoa Ministry of Health standard for achieving equity is that the proportion of Māori nurses matches the proportion of Māori in the population,20 which is 17 per cent.21

This indicates that Māori are currently underrepresented in the Aotearoa nursing workforce, and thereby likely to be under-represented in the perioperative nursing workforce. It is crucial that health-care organisations actively work towards recruiting Māori nurses as part of our te Tiriti responsibilities.

Local research

A recent Aotearoa study on nurse staffing practices in the operating room found that ensuring patients had their cultural needs met during their perioperative experience was an essential element of safe patient care.22 Findings support the need for nurses to understand and practice tikanga best practice.

The study identified that part of culturally safe patient care included accepting the patient as an individual with specific cultural needs. Findings indicated that culturally safe care includes ensuring that the patient’s cultural and religious beliefs are respected and supported, with family/whānau considered as part of the patient’s holistic care. Having family/whānau surrounding them was seen to be particularly important to Māori and Pacific patients. An example of this was making allowances for the family/whānau to come to the pre-operative area with the patient, so they could be with them right up to the time they go for surgery.22

Findings also indicated that to support provision of culturally safe care, training should be provided, which should include tikanga best practice.22

An identified limitation of the study was the lack of Māori nurse participants. One of the study’s recommendations was for further research to ascertain what culturally safe perioperative nursing care looks like from Māori nurse perspectives, as well as Māori patient and family/whānau perspectives.22

Conclusion

To ensure provision of culturally safe care, all nurses working in Aotearoa should have an in-depth understanding of the revised principles of te Tiriti o Waitangi. It is not enough to be able to cite the outdated “three Ps”. It is imperative that the health system ensures access to cultural safety training, and actively monitors all nurses in Aotearoa, whether new, senior or internationally qualified, for culturally safe practice.

Perioperative nurses must have knowledge of te Tiriti and an understanding of tikanga principles, including te Whare Tapa Whā model of health.23 More research is required on what more can be done to provide culturally safe care in the perioperative environment.

Source: Te Arai Research Group (2020). The Bicultural Whare Tapa Whā Older Person’s Palliative Care Model.

About the authors

Ko wai au?

Ko Maungataniwha te Maunga

Ko Tāpapa te Awa

Ko Ngātokimatawhaorua te Waka

Ko Mangamuka Marae te Marae

Ko Ngāpuhi te Iwi

Ko Rangi Blackmoore – Tufi tōku Ingoa.

Rangi Blackmoore-Tufi completed her nursing degree in Te Matau a Māui (Hawkes Bay) at Te Aho a Māui (Eastern Institution of Technology). She moved to Tāmaki Makaurau (Auckland) to start her nursing career which began in rehab/stroke under the NETP programme. She wanted to become more specialised and this is where she began her career in the perioperative department. While working in the perioperative department, Rangi identified culturally unsafe practices. She wrote an article based on her lived experiences. “A safe environment for Māori patients starts with a safe environment for Māori nurses”.

Rangi is now employed as a kaiārahi nāhi (clinical nurse specialist) working with Māori patients on the planned care pathway awaiting surgery. She also works part time in the community for an outreach team providing services to Māori and Pacific Island whānau. She is one of two proxies for the Tāmaki Makaurau region for Te Rūnanga o Aotearoa.

Bron Taylor, RN, MN (1st class hons) is the whakahaere nāhi/associate nurse director for āhua tohu pōkangia/perioperative services at Te Toka Tumai/Auckland, Te Whatu Ora. She completed a masters of nursing through the University of Auckland in 2021. Her research explored operating room nurse staffing in an Aotearoa context. She is the current chief editor of The Dissector.

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to acknowledge the support and assistance of senior nurse Elizabeth Kanivatoa and Dr Elizabeth Dunn whose mātauranga Māori (Māori knowledge), insightful comments, suggestions and feedback on this article was invaluable.

References

- World Health Organisation. (n.d.). Health Equity.

- Association of periOperative Registered Nurses (AORN). (2022). AORN Position Statement on Health Care Equity and Racial Justice. AORN Journal, 115(5).

- Curtis, E., Jones, R., Tipene-Leach, D., Walker, C., Loring, B., Paine, S. J., & Reid, P. (2019). Why cultural safety rather than cultural competency is required to achieve health equity: a literature review and recommended definition. International Journal for Equity in Health, 18(1), 174.

- Hamlin, L., & Anderson, L. (2011). Cultural competence and perioperative nursing practice in New Zealand. AORN Journal, 93(2), 291-295.

- Nursing Council of New Zealand. (2011). Guidelines for cultural safety, the Treaty of Waitangi and Maori Health in Nursing Education and Practice.

- Perioperative Nurses College of New Zealand Nurses Organisation. (2016). New Zealand perioperative nursing knowledge and skills framework.

- Nursing Council of New Zealand. (2007). Competencies for registered nurses.

- Ministry for Culture and Heritage. (2022). He Whakaputanga — Declaration of Independence.

- Orange, C. (2012). Treaty of Waitangi, Te Ara – the Encyclopedia of New Zealand.

- Nursing Council of New Zealand. (2020), Te Tiriti o Waitangi Policy Statement.

- Beri, K. (2019). Learning from the Waitangi Tribunal Māori health report.

- Ministry of Health. (2014). Tikanga ā-Rongoā.

- Victoria University of Wellington (n.d). Tikanga tips.

- Auckland District Health Board. (2013). Tikanga Best Practice Policy.

- Purdy, S. C. (2020). Communication research in the context of te whare tapa whā model of health. International Journal of Speech Language Pathology, 22(3), 281-289.

- Elias, J. (2018). Use of tikanga by Bay of Plenty District Health Board. Journal of MAOR202: Tikanga and Māori, 2, 125-131.

- Auckland District Health Board, (2021). Deceased (Tūpāpaku) +/- Referrals to the Coroner for an Adult, Child, Infant, Neonate or Stillbirth.

- Nursing Council of New Zealand. (2019). Te Ohu Mahi Tapuhi o Aotearoa/The New Zealand Nursing Workforce: A profile of nurse practitioners, registered nurses and enrolled nurses 2018–2019.

- Wilson, D. (2018). Why do we need more Māori nurses? Kai Tiaki Nursing New Zealand, 24(4), 2.

- Ministry of Health. (2018). Sector update from the Office of the Chief Nursing Officer November 2018.

- Statistics NZ. (2019). New Zealand as a village of 100 people: Our population.

- Taylor, B. (2021). Nurse Staffing in the Operating Rooms – No Longer Behind Closed Doors [Masters thesis, University of Auckland].

- Durie, M. (1994). Whaiora: Māori health development. Oxford University Press.

Both companion articles were first published in the June 2022 edition of The Dissector and are reproduced here with the permission of the authors and the Perioperative Nurses College national committee.