Shared medical appointments are at the heart of a quality improvement project at a fracture clinic.

The Ministry of Health says a quality improvement approach includes “an explicit concern for quality, vested in teams; the viewing of quality as the search for continuous improvement; an emphasis on improving work processes to achieve desired outcomes; and a focus on developing systems and investing in people to achieve high-quality health outcomes”.1

In this article, we describe a quality improvement initiative in a fracture liaison service. We aim to:

- Provide a case study of quality improvement in action, working within an existing service with patient-flow challenges.

- Share ideas and findings for others wanting to improve an existing service or establish a new one.

The fracture liaison service (FLS) in the MidCentral region is provided by the MidCentral District Health Board and the primary health organisation THINK Hauora. In this article, we focus on the primary care arm of this service, provided by THINK Hauora, and delivered by a clinical nurse specialist and one administrative team member.

This is a free service for people aged over 50 who have experienced a fragility fracture or a non-major trauma fracture, such as that resulting from a simple fall. This “signal” or “herald” fracture is a warning that may uncover reduced bone mineral density as in osteoporosis or osteopenia. The goal of the service is to decrease the risk of another fracture by doing a fracture risk assessment (FRAX)2 and putting in place a bone health care plan to be followed up by a general practice team (GPT).

Looking at bone density and assessing falls risks is the only post-fracture model of care that has shown a reduction in the risk of future fractures and the associated trauma and potential loss of independence.3

The population of this service tends to be female, of the baby boomer generation, and mainly European, Indian or Asian.4 (There are few Māori and Pacific people, as statistically they have the highest bone mineral density in the world.5) They are at high risk of loneliness as they age, often outliving their spouses. Loneliness is related to poor health outcomes.

The FLS introduced shared appointments as a new service delivery model in 2020 to improve efficiency, reduce duplication and address the service’s waiting list problem. The shared appointment is a single, two-hour session people attend with others to learn more about their condition. Within the session, they have a short, individual consultation with the FLS nurse to develop a care plan, including treatment recommendations. Individual appointments (either face-to-face or via the phone) are still offered where required.

As part of a more general quality improvement approach, two staff members external to the service (the health researcher and the nurse advisor for long-term conditions – co-authors of this article Claire Budge and Melanie Taylor) worked with the FLS team later in 2020 to streamline work-flow processes, and refine the delivery of shared appointments, emphasising patient self-management. This support is ongoing.

Approach

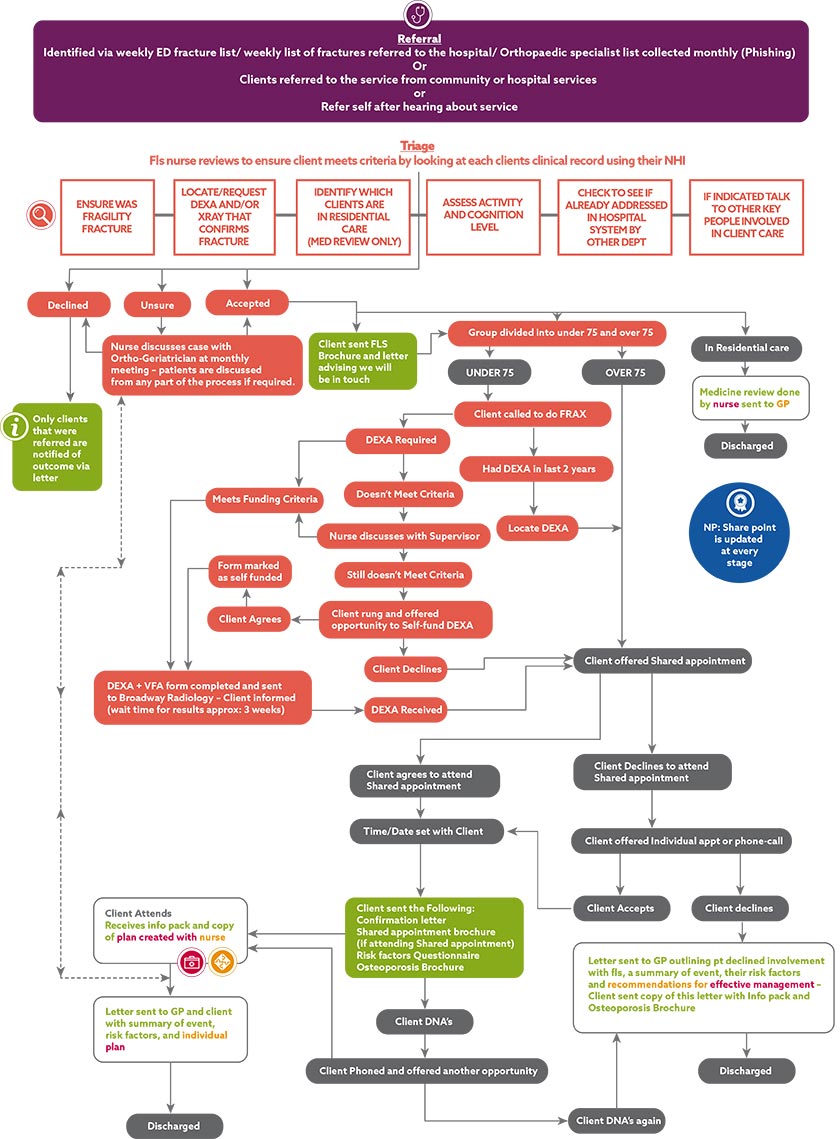

The quality improvement approach started with process mapping, which is the development of a flowchart documenting the steps in a process – in this case the patient pathway through the FLS. A guide to process mapping stated “…the data provided by process mapping can be used to redesign the patient pathway, to improve the quality or efficiency of clinical management and to alter the focus of care towards activities most valued by the patient”.6 A systematic review of 105 studies on the use of process mapping for quality improvement in health care identified a range of benefits. These included: breaking down complex systems; improved coordination of care across settings; identification of constraints and opportunities; enhanced understanding of roles and responsibilities; and the development of ownership and responsibility for improvement work.7

Process mapping involved talking to the FLS team about the patient flow through the service, starting with identification of patients (referral, self-referral, emergency department fracture list/fracture referral list/orthopaedic specialist list) and proceeding through what happened when and for whom. This depended on patient eligibility, for the service and for a free bone density (DEXA) scan, and their choice of a shared or individual appointment and follow-up. After multiple discussions with the team, notes and pathways were mapped out, culminating in the generation of a flowchart:

Download large version as a PDF (506 KB)

Process mapping allowed us to identify problem areas in the patient flow and, with the FLS team, we brainstormed ways of improving and speeding up processes. As part of this, we examined the patient communication processes and content, and made changes to brochures and letters and what was sent out when. Some of these changes related not only to communication but also to the shared appointment process.

An example was that a comprehensive falls assessment, including the collection of FRAX data for each patient, was being conducted during the shared appointment, which slowed down the group session. Instead, a questionnaire was developed to collect the necessary data and this is sent out to the patient before the shared appointment. They complete it at home and bring it along for discussion during the individual consultation component of the session. This speeds things up and also helps maintain confidentiality.

We also identified problems with the type and content of the service’s first approach to patients. Instead of initiating contact with a phone call, a package is now sent out first, including a letter introducing the service and preparatory materials. This means patients are forewarned about pending contact.

We reviewed the pamphlets and brochures that were sent out, and found some overlapping content. Also, the sheer amount of information was overwhelming, potentially resulting in none of them being read. We selected the best booklet – covering the necessary information clearly and concisely – to be posted out, making others available for patients to take home from the appointment. The guiding principles we used were to keep in mind health literacy (people’s ability to read, understand and remember health messages) and the attractiveness and friendliness of forms and brochures.

The shared appointments also required some modification. Shared appointments are where a small group of people with a common interest – in this case osteoporosis and a recent fracture – come together for education, individual assessment and discussion. In the FLS, it is a single session; other types of shared appointments can involve the same group of people meeting on a regular basis. The repeated meeting format, often used in diabetes care but also effective in osteoporosis management,8, 9 allows attendees to build relationships with each other and learn from their experiences, giving and receiving support along the way:

Benefits of shared appointments for patients and providers

- Combat isolation and encourage patients to realise they can manage their condition.

- Encourage vicarious learning by patients as they witness others’ illness experiences.

- Patients feel inspired by successful peers.

- Build friendships between patient and providers.

- Improve collegiality between providers.

- Providers learn from patients how to meet their needs better.

- More time helps patients feel comfortable and better supported.

- Improved health knowledge for patients through input from providers and peers.

- Seeing the provider interact with other patients builds trust.

Statements like ‘my fracture hurt for weeks and still aches now’ are commonplace and participants reassure each other, creating a bond of shared trauma.

In a single session, there is less scope for these outcomes to be realised, but in our one-off intervention it was noted that participants benefitted from talking about the fracture and how it occurred. Statements like “my fracture hurt for weeks and still aches now” are commonplace and participants reassure each other, creating a bond of shared trauma. Attendees can gain insight from other people’s experiences and learn from people asking different questions or bringing different ideas to the discussion. One big advantage is the amount of time dedicated to patient education and promoting self-management.

The content of the shared appointment is similar to that of the individual sessions, but the longer running time means more detail and group discussion can be incorporated. It includes information on bone density and osteoporosis, avoiding future fractures and falls, exercises for strength and balance and dietary advice (calcium and vitamin D). Also DEXA scans are explained and reviewed.

As part of the new approach, attendees are encouraged to work out a plan for themselves and set goals to improve their bone health and limit the likelihood of another fracture. Medicine management is discussed in the individual appointment.

Initially the shared FLS appointments were not well attended. This was partly due to there being too many time slots on offer, in two locations. However there was also a non-attendance issue, as around 10 people were being booked in but only a few were turning up. We addressed this by reducing the number of time slots, overbooking the sessions to allow for some non-attenders, putting in a reminder system, offering payment of taxi fares if transport costs were an issue and writing an information brochure on shared appointments. The brochure was sent out as part of the preparatory materials so people had more understanding of what to expect.

Another major change was to add a group facilitator to the shared appointment team, in line with suggestions made in the Self-Management Support Toolkit. It was an obvious choice to teach the FLS administrator the necessary facilitation skills, as she was passionate about and committed to this work. This change has enabled the nurse to focus on clinical care while the facilitator focuses on group dynamics and the flow of the session. It is important to keep her role within scope however, as she is non-clinical and clinical questions raised by participants are put aside to be addressed by the FLS nurse later in the session.

We also invited THINK Hauora’s clinical quality facilitator, who is experienced in running group self-management programmes, to sit in on some sessions. He helped redesign the self-management component to maintain the flow of the session while facilitating patients stepping out for their individual nurse consultations.

We wanted to ensure participants did not feel they were just waiting to see the nurse and that they could all participate in key self-management activities. The process was adjusted by moving the tea break to the start of the self-management session and introducing some self-management activities aimed at making lifestyle change options personally applicable. This session incorporates three main activities:

- identifying home safety and prevention of falls;

- looking at diet to increase calcium intake; and

- practising a recommended exercise regimen.

Feedback to general practice

Another area that required streamlining was the feedback provided to the GPT. The FLS nurse had been typing lengthy letters for the GPT for each patient she had seen, to inform them of the patient’s fracture risk, and summarise her review and treatment recommendations. This process was extremely time-consuming, slowing down patient flow.

Having the comprehensive falls assessment as a questionnaire enabled her to scan the completed form and attach it to a shorter letter, with instructions to the reader to review the patient’s self-reported assessment. In addition to medicine management recommendations, she also now includes information about the patient’s goals and intentions for self-management. This can contribute to a more comprehensive care plan being developed with the patient when they next see a member of their GPT.

Using quality cycles

Throughout the whole process, a Try, Learn and Adjust approach to quality cycles was adopted (from work in the disability sector in the MidCentral region through Mana Whaikaha). A form was drawn up to enable ongoing documentation. This involves coming up with a possible solution to a problem or a new approach, implementing it, and then learning from the experience and making adjustments until the new idea is integrated into business as usual – or discarded if it doesn’t prove useful:

QUALITY CYCLES: Try, learn & adjust

Date: March 2021.

Topic: Addressing poor attendance at shared appointments.

Issue: People are invited to a shared appointment and then don’t attend.

TRY (What are we developing?)

- Invite 10-12 people for each session.

- Reduce the frequency of appointments to fill sessions – one in Palmerston North and one in Horowhenua each month.

- Develop a brochure explaining what a shared appointment is so patients are better informed and to make shared appointments more attractive.

- Put a system in place to pay for taxi at front office if transport is an issue.

LEARN (How are things working?)

- FLS team has more time to do other work due to spacing of shared appointments.

- Increased attendance recently – this may result from introducing the shared appointment brochure.

ADJUST (What does this mean for what we do next?)

- We need to put additional shared appointments into the calendar as more people are now attending.

- An alternative approach is needed when more than 10 people attend, as individual consults result in lengthy delays. The initial suggestion is to divide the group into those who can have a consultation that day, and others who will receive a phone call to complete this work.

- We will consider including a clinical pharmacist at shared appointments.

Outcomes

There is evidence that all members of the team are learning from the QI experience and are now asking questions of themselves when a new situation or challenge arises. QI is becoming the norm and the team can identify areas requiring change without bringing them to the QI meetings. Big issues, such as those related to funding or major obstructions in the system, are shared with management and the broader FLS team, with the goal of simplifying work flow. Real, and well thought through solutions are being identified for consideration (see flowchart).

Staff are feeling better supported by the organisation and energised and motivated to keep trying new approaches. Improving patient experience and strengthening self-management remain at the core of service delivery.

The pre-appointment communication appears to be paying off as attendance rates have significantly improved, reducing waiting times for appointments and improving patient flow through the service.

Insights gained

Shared appointments: Attendees did not immediately understand or accept they now had a long-term condition requiring ongoing management and lifestyle changes.

This could be because their fracture had healed and bone density messages were less salient for them or the meaning hadn’t sunk in through the education they were receiving.

More effort needs to be put into repeating the message and ensuring it has been heard. It is important that general practice picks this up when discussing medicine management.

Providing practical activities to encourage conversation and consolidate learning during the individual appointment session has proved beneficial. In the future, another practitioner may be needed to halve the time taken for individual assessments.

Taking people out of the session for individual consultations requires careful management by the facilitator who needs to be aware of who has missed what and to make sure they have all got what they need.

Overall: It was helpful having somebody from outside the service look at processes and materials to see how they could be improved. People working in the service may not have the time, energy or ability to take an objective look at how things could be done differently.

When a service is being run by a limited number of staff, any staff absences immediately affect work flow and the way the system operates. This needs to be accommodated in the service plan.

In implementing a quality improvement cycle (in this case Try, Learn and Adjust), it was difficult to get staff members to document the steps as they went. When asked, they were able to verbalise the process of identifying a problem, thinking about how to address it and making changes, but they found it hard, or did not prioritise it as important, to translate this to paper.

The process is time-intensive and involves, as a starting point, getting a sense of how other similar services are set up and what the literature says about best practice. Websites such as the Self-Management Support Toolkit are a great starting point.

Conclusions

In this article we have described a quality improvement activity to enhance the efficiency of a primary based small-scale fracture liaison service. Changes have been made to improve the patient experience – particularly in relation to patient flow. By adjusting the roles of the staff involved, improving the communication processes and patient letters/brochures, and strengthening the shared appointment format, we were able to improve attendance and manage the pressure in the system better.

One of the reasons this QI effort was successful is that the people involved were open to and ready for change. Organisational readiness for change requires a shared commitment and belief in the capability to make it happen. Where organisational readiness is strong – as in this case where there was support from THINK Hauora to make changes and commit resources and the FLS team were prepared to listen, invest effort and try – effective change is more likely to happen.11

With the recent national drive to standardise and optimise the identification and treatment of people with osteoporosis, and new Osteoporosis New Zealand FLS clinical standards recently released,12 the FLS needs to remain responsive to change. Even with additional resources, the likely increase in patient numbers means the team will need to continue to identify areas for improvement, and do this in a way that does not compromise patient understanding and commitment to their ongoing self-management.

Claire Budge, PhD, is a health researcher for THINK Hauora, a primary health organisation based in Palmerston North.

Melanie Taylor, RN, MN, is a nurse advisor on long-term conditions at THINK Hauora.

Paula Eyres, RN, BN, PGCert, is a clinical nurse specialist in the fracture service at THINK Hauora.

References

- Ministry of Health. (2003). Improving Quality (IQ): A systems approach for the New Zealand health and disability sector. Ministry of Health.

- Kanis, J. A., Johnell, O., Oden, A., Johansson, H., & McCloskey, E. (2008). FRAX and the assessment of fracture probability in men and women from the UK. Osteoporosis International, 19, 385–397. doi.org/10.1007/s00198-007-0543-5

- Harvey, N. C. W., McCloskey, E. V., Mitchell P. J., Dawson-Hughes, B., Pierroz, D. D., Reginster, J-Y., Rizzoli, R., Cooper, C., & Kanis, J. A. (2017). Mind the (treatment) gap: A global perspective on current and future strategies for prevention of fragility fractures. Osteoporosis International, 10. doi.org/10.1007/s00198-016-3894-y

- Cauley, J. A. (2011). Defining ethnic and racial differences in osteoporosis and fragility fractures. Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research, 469(7), 1891-1899. doi.org/10.1007/s11999-011-1863-5

- Reid, I. R., Mackie, M., & Ibbertson, H. K. (1986). Bone mineral density in Polynesian and white New Zealand women. British Medical Journal (Clinical Research Edition), 14, 292(6535), 1547-1548.

- Trebble, T. M., Hansi, N., Hydes, T., Smith, M. A., & Baker, M. (2010). Process mapping the patient journey: An introduction. British Medical Journal, 341, c4078. doi:10.1136/bmj.c4078

- Antonacci, G., Lennox, L., Barlow, J., Evans L., & Reed, J. (2021). Process mapping in healthcare: A systematic review. BMC Health Service Research, 21, 342. doi.org/10.1186/s12913-021-06254-1

- Al-Ashkar, F. T., Hall, R. J., & Tsai, M. (2009). Lessons learned from shared medical appointment for osteoporosis management. Osteoporosis International, 20(suppl. 2), S227.

- Baqir, W., Gray W. K., Blair, A., Haining, S., & Birrell, F. (2020). Osteoporosis group consultations are as effective as usual care: Results from a non-inferiority randomized trial. Lifestyle Medicine, 1, e3. doi.org/10.1002/lim2.3

- Kirsh, S. R., Aron, D. C., Johnson, K. D., Santurri, L. E., Stevenson, L. D., Jones, K. R., & Jagosh, J. (2017). A realist review of shared medical appointments: How, for whom and under what circumstances do they work? BMC Health Services Research, 17, 113. doi:10.1186/s12913-017-2064-z

- Weiner, B. J. (2009). A theory of organizational readiness for change. Implementation Science, 4, 67. doi.org/10.1186/1748-5908-4-67

- Osteoporosis New Zealand. Clinical Standards for Fracture Liaison Services in New Zealand

This article was reviewed by Shell Piercy, RN, PGDip, BHSc, a clinical nurse educator at Eastcare Urgent Care Clinic, Auckland, and an emergency department nurse and research assistant at Counties Manukau District Health Board.