“We have a great opportunity to really think about the reality we want to create as we move forward,” McCormack told the NZNO college of gerontology nursing at their virtual symposium in October, via video. “And actually it may not be just tweaking what we had before, but actually building a new model of older people nursing, which embraces the creativity and the energy that we bring to it as older people nurses and help us to enable everybody to flourish in their lives.”

Person-centred practice was becoming a “truly global movement”, he said, informing health strategies and systems worldwide, including the World Health Organization and Institute for Health care Improvement.

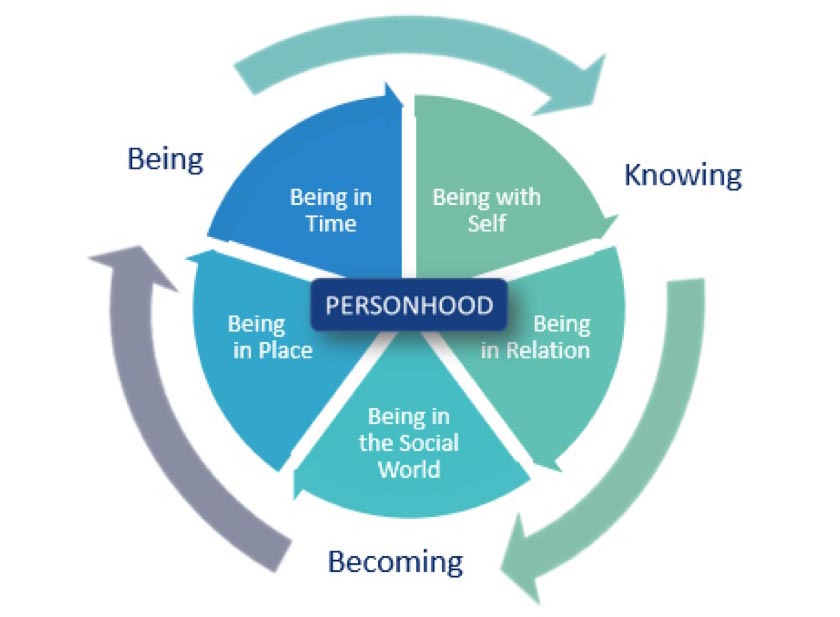

At its heart, the practice was based on the notion of “personhood”, defined by different states of “being” (Figure 1). It is underpinned by the idea all people are equal and need to flourish – a concept originally from Aristotle. McCormack quoted the Greek philosopher saying: “If I am not flourishing, I am languishing and languishing is a state worse than death.”

A person-centred approach considered the needs, culture and values of the person being cared for, but was more broadly based around relationships – with patients, residents, colleagues, managers, leaders and beyond.

This reflected the importance of flourishing for staff also, McCormack said.

“When we flourish, we are at our best, we are giving our best and we are able to give and receive loving kindness, that is we are able to connect with others in a loving way.”

Danish philosopher Knud Ejler Loegstrup argued it was through our attitude to each other that we helped shape each others’ worlds – and this was particularly true for nurses, whose “core function” was to help others flourish, McCormack said.

“As nurses, it’s really important to think about that power that we have, particularly when working with older and perhaps vulnerable older people, he said. “We can make their world big or small; it can be drab or bright and rich… threatening or secure”.

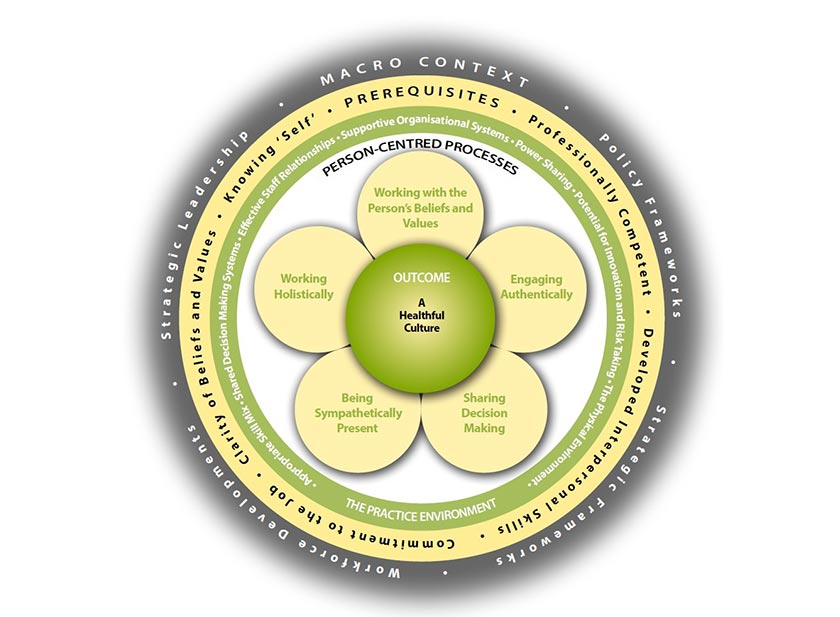

A person-centred care practice framework (Figure 2) developed by McCormack and Tanya McCance, of Ulster University in Northern Ireland, provides a guide for curricula, strategies, policy and research in more than 29 countries. It suggests five qualities needed for person-centred practice are: knowing “self”; clarity of beliefs and values; professional competence; interpersonal skills and commitment to the job – the idea of being “present” at work and “bringing all of myself to the situation”, McCormack said.

However, the care setting must also be supportive of person-centred values, with shared power and decision-making, strong relationships, good skill mixes and potential for innovation.

COVID-19

Social distancing and the use of things like masks had made it harder to maintain connection with residents, McCormack said. However, there had also been some “beautiful” practices emerging, such as rainbow boxes with comforting items, comfort pebbles and other “creative ways of being present”, McCormack said – including multi-media and the use of virtual reality, particularly in dementia and end-of-life care.

Massachusetts organisational developer Otto Scharmer has talked about COVID-19 being an opportunity to “pause, reset and step up”.

McCormack, too, believed COVID-19 was an opportunity to look at aged care. “We do have a choice here. We can freeze and just wait for it all to return to some kind of normal. Or we can look at what choices we have. How do we create a world that’s more compassionate and more person-centred, that enables us all to flourish?”

Carers had described person-centred care as the chance to leave a mark, or “imprint”. “As a nurse, the thing I want to do most is to leave an imprint on the people I connect with and something that makes them feel they’ve had a good experience.”

Rules vs patterns

But no matter how person-centred a practitioner was, it wouldn’t work without a supportive environment.

McCormack believed aged care needed to move away from a “rule-bound” culture and look at “patterns” in care homes. “They exist in the energy that we share, through the unspoken practice we all engage in, but they generally always shape the day-to-day world we create in rest homes.”

There were seven typical patterns residents engaged in:

- The dining experience

- Entering and leaving

- Getting up and settling down

- Social milieu

- Personal care

- Private, secret spaces

- Dying and death

Knowing these areas allowed the opportunity to create a “flourishing” culture, focused on creating positive patterns in the home.

Staff also needed to ensure positive patterns in their teams, with power-sharing and building nurturing relationships and positive ways to deal with conflict.

McCormack said it was important for gerontology nurses to be flexible – “having that fleetness of foot” – to work with older people, particularly those with dementia. “We have to travel through time all the time if we want to be person-centred with them”.

Find out more at Places to Flourish.